The Fed Knows What It's Doing. Relax.

Inflation is too well contained to think the Fed will blindly raise interest rates to a level that restrains the economy.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The minutes of the September Federal Open Market Committee meeting confirmed speculation that Federal Reserve policy makers are leaning toward pushing interest rates above levels considered to be neutral, which neither stimulate nor restrain the economy. That sounds ominous, but it is important not to worry too much yet over the prospect of restrictive policy.

Fed forecasts are a projection, not a promise. If the economy stumbles, odds are the Fed will react appropriately and ease policy. There, however, is an important exception to this rule. If inflation looks to be stirring, the Fed will likely tighten down the clamps. That’s when the real worrying should start, but the Fed does not appear near that point yet.

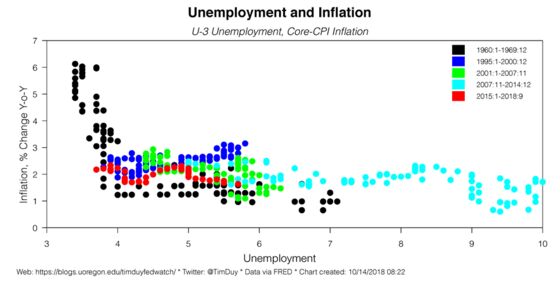

Policy makers are navigating an environment with a disturbing historical precedence. The unemployment rate is the lowest since the late 1960s. Then, like now, the Phillips curve – the relationship between unemployment and inflation – was seemingly flat. And then it suddenly wasn’t and inflation began jumping higher, setting in motion the Great Inflation of the 1970s. Low unemployment is not the only precedent. Then, like now, fiscal spending was ramping up even as unemployment fell.

Of course, the Fed does not anticipate a repeat of the inflationary consequences of low unemployment in the 1960s. They expect gradual rate hikes to sufficiently diffuse price pressures and hold inflation expectations in check. So far, the plan appears to be working. The September Consumer Price Index report revealed another month of tame inflationary pressures.

As long as inflation pressures remain contained, the Fed has the capacity and, I believe, willingness to respond to threats to the economy. Consider the Fed’s first effort to raise rates in this cycle. Central bankers boosted rates in December of 2015, but subsequently realized that economic weakness stemming from falling oil prices and a stronger dollar were thwarting their plans to continue to tighten monetary policy. They soon went into an extended pause, holding policy steady for a full year. That change in trajectory allowed the economic expansion to continue.

I think the Fed would respond in a similar manner to an economic threat today. The situation would change if the inflation outlook were to deteriorate such that policy makers sensed inflation expectations would drift upward and beyond their target of 2 percent. Under such circumstances, the Fed would believe inflation is the dominant risk for the economy. That is when it will choose a policy path with a greater risk of recession. Market participants should be watching for signs that Fed thinking is evolving in that direction.

The FOMC minutes confirm that the Fed has yet to panic about inflation. To be sure, central bankers recognize that rising input costs stemming from wages and tariffs are increasing pressure on firms to raise prices. Importantly, though, central bankers continue to think conditions are consistent with their tame inflation forecasts. And, perhaps even more importantly, the minutes note that “[s]everal participants commented that inflation may modestly exceed 2 percent for a period of time.”

This indicates that Fed thinking – at least for now – does not anticipate an aggressive response to modestly higher inflation. Likewise, they would probably anticipate that a weaker growth trajectory than expected would cause inflationary pressures to wane, thereby justifying an easier policy stance.

When I look for downside risks, I generally look for periods in which the Fed is unwilling or unable to respond to deteriorating economic conditions due to inflation concerns. That’s when the Fed is most likely to allow a shock to turn into a recession. A series of inflation shocks, such as tariffs and higher energy prices, in a full employment, fiscal stimulus-charged economy could create such conditions. But so far, they haven’t. That tells me the Fed is not likely to risk allowing this expansion to end just yet. Absent an inflationary threat, you should bet that there is a "Powell put" for the economy. We are just nowhere near triggering it yet.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at bburgess@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tim Duy is a professor of practice and senior director of the Oregon Economic Forum at the University of Oregon and the author of Tim Duy's Fed Watch.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.