McDonald’s CEO Wants Big Macs to Keep Up With Big Tech

McDonald’s CEO Wants Big Macs to Keep Up With Big Tech

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Three years ago, Steve Easterbrook ran out of patience. Before flying home to Chicago for the Christmas holidays, he stopped in Madrid to meet with Spanish executives from McDonald’s. In a conference room at the company’s local office off the A6 highway, the mood soured as managers lamented heavy losses on the evenings when FC Barcelona and Real Madrid C.F. competed. Diners were staying home and ordering from archrival Burger King for delivery—a service McDonald’s didn’t offer.

Conceding to Burger King in any circumstance is an indignity, but losing hundreds of thousands of customers to the enemy’s modernized tactics during one of Spain’s most important weekly fixtures was the final straw. It represented everything that was defective at the business Easterbrook had been running for 22 months—McDonald’s Corp. was just too analog. A week before he was named chief executive officer, the company announced it had suffered one of its worst years in decades as dejected U.S. customers abandoned the brand for Chipotle burritos and Chick-fil-A sandwiches. In the U.K. hundreds of artisanal burger competitors had appeared seemingly overnight on the food-delivery mobile app Deliveroo, which indulged the couch potato demographic with an unprecedented ease of access that felled the appeal of McDonald’s drive-thrus. The time had come to address a weakness that stretched far beyond the company’s Iberian territories.

“He looked at me and said, ‘We’re not going to go through the traditional market pilot and study delivery for six months. We’re just going to do it,’ ” says Lucy Brady, who oversees McDonald’s global strategy and business development teams. He instructed her to get every country manager on a conference call on Monday morning.

Brady cautioned him that it might be difficult to reach some managers who’d already left for the holiday; Easterbrook said everyone could spare a half-hour. He would command each manager to nominate their best executive to the task of building an online delivery business that would aim to be fully operational by the beginning of January—in two weeks’ time. When Brady suggested they target delivery from 3,000 restaurants by July 1, he told her he would be disappointed if they didn’t get to 18,000—about half of McDonald’s locations around the globe.

Management’s compensation would be tied to the speed and breadth of the rollout, and the only limiting factor Easterbrook would accept would be the number of couriers in cars, on bikes, and on foot that their delivery partners could supply. For the widest possible deployment, McDonald’s teamed with Uber Eats. The partnership was so significant that Uber Technologies Inc. devoted two full pages to its then-exclusive delivery agreement with McDonald’s in a roadshow prospectus ahead of Uber’s initial public offering in May. Easterbrook now regularly uses the service while traveling on business to gauge its quality.

“I’m a Quarter Pounder guy,” he says with a calculated slowness not unlike Daniel Day-Lewis’s “I’m an oil man” in There Will Be Blood. The 52-year-old British CEO has the tall, broad frame of a rugby player, with thick waves of black hair and piercing blue eyes. He’s described as an inscrutable blend of mild manners and obsessive competition by members of his fresh-faced leadership team. (Upon taking the top job in 2015, Easterbrook fired or let go 11 of the 14 most senior executives he inherited.) He expects the delivery business to account for about $4 billion in sales by the end of this year.

Catching up to Burger King on delivery would be the first item on a long list of improvements Easterbrook already had in mind for McDonald’s. Broadly, he wants to reconfigure his restaurants into enormous data processors, complete with machine learning and mobile technology, essentially building the Amazon of excess sodium. Franchisees have balked at the costs of implementing his vision, which includes drive-thrus equipped with license-plate scanners (the better to recall one’s previous purchases) and touchscreen kiosks that could ultimately suggest menu items based on the weather.

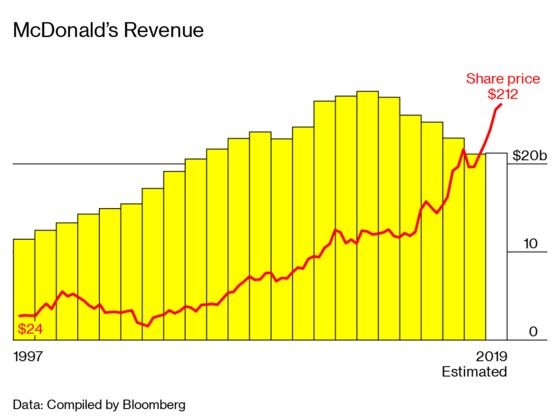

So far, the strategy has proved compelling: Only a handful of other companies in the S&P 500, almost all of them California technology suppliers such as semiconductor giant Advanced Micro Devices and chipmaker Nvidia, have outperformed McDonald’s returns since 2015. The gains have generously rewarded institutional investors like BlackRock Inc. and Vanguard Group Inc., who’ve long been among the chain’s largest backers. Easterbrook wants to reclaim the company’s image as a beacon of innovation, a designation McDonald’s hasn’t enjoyed since roughly the Truman administration.

In 1940 brothers Dick and Mac McDonald redesigned and rebuilt their modest hot dog drive-in, in the shadows of California’s San Bernardino mountain range, into McDonald’s Bar-B-Q, which sold 25 items. By 1948 they dropped “Bar-B-Q” from the name and streamlined the menu to offer only the most profitable foods: hamburgers, cheeseburgers, potato chips, coffee, soft drinks, and apple pie. The restaurant seated about a dozen customers on outdoor stools and sold 15¢ hamburgers, which were bagged within 30 seconds of being ordered thanks to the pioneering Speedee service system.

The system had begun with the brothers sketching out life-size kitchen blueprints on a tennis court with chalk and having employees act out cooking and serving tasks. After settling on the fastest method, they contracted kitchen equipment companies to build machinery to support the choreography. Breakthroughs included custom-made saucing guns for the buns and curved steel ramps on which burgers would slide down into cashiers’ hands to pass on to diners. At the time, only a handful of burger chains were using similarly bespoke hardware.

No one was as passionate about McDonald’s potential for expansion as Ray Kroc, a struggling milkshake machine salesman from Illinois who met Dick and Mac at their restaurant in 1954 on a business trip. McDonald’s had by far the most efficient kitchen he’d ever seen, and he immediately lobbied the brothers to let him franchise the business. In 1961 he bought out the co-founders for $2.7 million, and in 1965 he took the company public. Today, McDonald’s is the world’s most recognizable restaurant empire and a formidable real estate venture—its franchising model has earned the company a fortune by acquiring and subsequently leasing the land beneath stores to their operators.

For a half-century, McDonald’s greased its way onto every continent except Antarctica. It stayed ahead of scores of copycats, but the baby boomer loyalty that propped it up has steadily waned. It’s also become something of a cultural laggard. The suitability of McDonald’s in a looming Age of Kale was aggressively pondered in Super Size Me, the 2004 documentary film in which director Morgan Spurlock attempts to subsist on the restaurant chain’s food for a month. He cast the company as an abhorrent peddler of heartburn and substandard bowel movements. There’s also the inevitable discomfort of being one of the world’s largest purchasers of beef and poultry. Younger generations concerned about the environmental cost of industrialized meat are opting for plant-based alternatives such as Beyond Meat and the Impossible Burger, which is now available at Burger King. Animal-rights activists regularly erect giant inflatable chickens with bereaved expressions on the sidewalk outside McDonald’s new head office in downtown Chicago.

The company boasts a market valuation of $159 billion and an immense global reach, feeding about 1% of the human population daily. But even in the fast-food realm it dominates, its share of the U.S. market has shrunk to 13.7% from 15.6% in 2013, according to data from Euromonitor International, ceding ground to Pret a Manger and Panera Bread Co. In the burger wars, it’s been besieged by cooler competitors with cult followings, including Shake Shack, Five Guys, and In-N-Out. Earnings began to stagnate at McDonald’s in 2013 and crashed by almost a fifth, to $4.7 billion, the following year as diners deserted. Four months before stepping down in March 2015, Don Thompson, Easterbrook’s predecessor, lamented that the company had failed to evolve “at the same rate as our customers’ eating-out expectations.” As insurgents claimed an ever-growing share of the market McDonald’s had created, the morale at the old headquarters in Oak Brook—a tranquil if uninspiring 1970s amalgam of gray cubicles set in a parkland in Illinois—began to sap. The company’s strategic quagmire took on a superstitious quality when the estate itself became a hive of bad omens, with parts of the office complex flooding on an annual basis.

Easterbrook became global chief brand officer in 2013. The following year, he traveled to Cupertino, Calif., to sit down with Tim Cook, Apple Inc.’s CEO, to discuss being a launch partner for the Apple Pay mobile payment system. The card readers McDonald’s used lacked the necessary technology, so Easterbrook had a digital add-on installed on every machine at its 14,000 locations in the U.S.

Easterbrook first joined McDonald’s in the finance department in London in 1993, and spent the majority of his career there. After graduating with a natural sciences degree from Durham University, where he played competitive cricket alongside the future England captain, he worked as an accountant for the partnership that would become PwC. He later worked as a restaurant manager for McDonald’s before being named to head its U.K. division, which he turned around in the 2000s after years of waning sales. In that role, he mounted a defense against fast-food critics by debating them on live television. He revitalized the company’s image as a family-friendly outlet by introducing organic milk, cutting the fries’ salt content, and offering free Wi-Fi. He also tried unsuccessfully to get the Oxford English Dictionary to amend its definition of “McJob,” a slang term used since at least 1986 that denoted “an unstimulating, low-paid job.”

In the fall of 2014, McDonald’s went public with “Experience of the Future,” an initiative Easterbrook had been shepherding. It reimagined the store entirely, from how orders were placed to what services were offered. In the upgraded restaurants, diners can use touchscreen kiosks to customize their burgers into millions of permutations, such as adding extra sauce and bacon to a Big Mac. The thinking was that giving customers more say over their orders would result in them paying more for tailored items. Some franchisees have benefited so much that their restaurants’ sales are now growing at a double-digit rate. But others have banded together in open rebellion and forced the company to slow the program’s full rollout two years past its original target. They object to the enormous costs of the project, which, for owners of several locations, can run into tens of millions of dollars, even with McDonald’s offering to subsidize 55% of the capital for the remodels.

From a business perspective, the enhancements are achieving what they set out to do—annual profits have inched higher since Easterbrook’s appointment, and McDonald’s posted its fastest global sales gain in seven years last quarter. Initiatives such as all-day breakfast, which includes the staple McMuffin, and new products like doughnut sticks are also credited with bringing customers back even as the expanded menu hampers the classic McDonald brothers’ efficiency.

The company has also introduced a curbside pickup system. An order placed through the McDonald’s app automatically appears on the store’s order list when the diner’s phone is within 300 feet of the property. The food is prepared and delivered to the curb by floor employees. The workers and franchisees who’ve long complained about low hourly wages and poor working conditions in campaigns such as Fight for $15 have generally taken a dim view of Easterbrook’s overhaul. Westley Williams, a Floridian in his early 40s, says the initiatives and the chaos caused by mobile app orders, new items, and self-order kiosks riddled him with so much anxiety that he defected to nearby burger chain Checkers. “It’s more stressful now,” said Williams, who added that he didn’t get a raise for doing more work. “When we mess up a little bit because we’re getting used to something new, we get yelled at.”

Concerns about staff welfare have become a major issue for McDonald’s in the U.S., where the median pay for food and beverage service workers is $10.45 an hour. Accusations of coercion soared this year after workers filed a total of 25 claims and lawsuits alleging endemic sexual harassment. The complaints have since become a national conversation and part of the political fabric: In June a group of eight senators led by Democrat Tammy Duckworth of Illinois and including 2020 Democratic presidential candidates Bernie Sanders of Vermont, Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, Kamala Harris of California, and Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota sent a letter to Easterbrook decrying “unsafe and intolerable” conditions and “unacceptable” behavior in the chain’s restaurants.

Carlos Mateos Jr., whose family owns 21 stores near Washington, D.C., says Easterbrook’s modernization has succeeded in attracting new customers to his restaurants, but revamping everything simultaneously was a burden. About a quarter of his franchises still need to be remodeled. “There’s training that’s involved. We have to get the employees ready for it—mobile order and pay and Uber Eats and kiosks. All these different things are happening at the same time, and it really took a toll on us.”

Adding an Uber Eats counter for delivery, touchscreen kiosks, modern furniture, and power outlets to charge mobile phones means franchisees incur additional costs from $160,000 to $750,000 per restaurant, McDonald’s has said. Blake Casper, a Tampa-based franchisee who operates more than 60 McDonald’s and founded the National Owners Association last fall to resist Easterbrook’s amelioration plan, would theoretically have to fork over at least $5 million to make the CEO’s dream a reality.

“I would like to make the kitchen as stress-free as it possibly can be,” says Eli Asfaw, who operates seven franchises in the Denver area. For a start, scaling back rollouts mandated by the company, such as all-day breakfast, would “make it easier for us to keep people and make our people happy.” Asfaw also says the remodeling plan has heaped pressure on owners, from financial headwinds to the tight window in which the company wants the upgrades to be completed.

The resistance from a faction of franchisees to Easterbrook’s mandated remodels—in some cases drastic enough to require a restaurant to be razed and rebuilt—reached a breaking point in January. The National Owners Association wrote in a letter to its 400 members then (it now counts more than 1,200) that the changes should be halted amid concerns about eroding profits and the costs of implementing Experience of the Future. “To put it bluntly,” the letter read, “stop everything that is not currently in the works.”

Easterbrook concedes his rollout hasn’t been perfect. “We were just going so hard at it, it proved to be a bit of a handful,” he says of introducing the features in the U.S., many of which had already been phased in years before in France and Australia. While franchisees were right to put off remodeling to ensure they weren’t distracted from efficiently running their restaurants, the domestic business was in dire need of a significant revamp, he says. The number of customers visiting U.S. stores had been declining in the last half of his predecessor’s tenure. “It was pretty obvious we were operating and moving slower than the outside world, and customers were voting with their feet.”

In November, McDonald’s said it was slowing the pace of remodels in the U.S. The conversations are often fraught. When Easterbrook invited eight franchisees to break bread with a group of McDonald’s executives at a steakhouse in Washington, D.C., in April, one operator accused him of saddling stores with impossible demands. For longtime managers who back Easterbrook’s goal and enjoy the internal energy it’s created, the prospect that his plans could fall through is unthinkable.

“When they ask a question that’s a bit of an attack, I sit there and get a little pissed, because I’m ready to lean in,” says Charlie Strong, a 66-year-old McDonald’s executive who oversees more than 5,700 restaurants across the western U.S. He affixes a lapel pin of the letter “M” in the style of the golden arches logo to a navy Brooks Brothers blazer, and his right pinkie is weighed down by a 14-karat yellow gold ring inset with five diamonds, onyx, and the golden arches. The company gave it to him to celebrate his 25th anniversary with McDonald’s. He expects to receive another for his 50th in two years.

Strong says one of Easterbrook’s key qualities is that he doesn’t take any criticism of his strategy personally. “He just rolls with it and swings it back to what’s important about the business, what’s important about the vision, and to not get bogged down with these little things along the way.”

Easterbrook’s strategy so far has been vindicated by the numbers. That tailwind is breathing new life into the business. Strong drives 40 miles from his home in Aurora, Ill., every morning to be at his desk by 6 a.m., where he and a handful of other masochistic early risers blast rousing tunes by Journey or Adele on a Bose sound system to get the day going. It’s a routine they began after moving into the new head office, a $250 million building replete with sofa pods in the red and yellow McDonald’s color scheme, an amphitheater, rooftop terraces, and thousands of antique and modern Happy Meal toys locked inside cased glass like priceless museum specimens. Easterbrook opened the office in June of last year in a bid to attract young, tech-forward talent.

In March, McDonald’s acquired artificial intelligence startup Dynamic Yield, headquartered in New York and Tel Aviv, for $300 million—the company’s largest acquisition in 20 years. The burger chain had been testing the machine learning software on drive-thrus at four restaurants in Florida, where screens automatically updated with different items based on the time of day, restaurant traffic, weather, and trending purchases at comparable locations. That technology has been deployed at 8,000 McDonald’s and counting, with plans to be in almost all drive-thrus in the U.S. and Australia by the end of the year, Easterbrook says. The deal signaled an ambition to align the chain with the same predictive algorithms that power impulsive purchasing on Amazon.com or streaming preferences on Netflix. In April, McDonald’s acquired a minority stake in New Zealand-based mobile app vendor Plexure Group Ltd., which helps restaurants engage with diners on their phone with tailored offerings and loyalty programs. The effort falls into the consumer-goods industry’s wider trend toward micromarketing, which has proved effective in driving sales.

In early September, McDonald’s said it was buying Silicon Valley startup Apprente Inc., a developer of voice-recognition technology. The idea is to help speed up lines by eventually having a machine, instead of a person, on the other side of the intercom to relay orders to kitchen staff. The deal for Apprente is McDonald’s third such investment in a technology business in the past six months as the company shakes off a tamer takeover strategy that for decades had focused on buying and selling restaurants from or to operators. McDonald’s is pursuing this new business model even as the latest burger trends steal the buzz from its offerings. Beyond fashionable vegan patties, a new and daunting foe is the fried chicken sandwich at Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen (a Miami-based chain owned by the same company that controls Burger King), which became a national obsession when it was introduced in the U.S. in August.

McDonald’s has leased space in a discreet industrial complex more than an hour away from headquarters, where a gray building about the size of an aircraft hangar, with a single column painted yellow and dotted with sesame-seed stencils, has become a testing ground for putting Easterbrook’s thoughts into practice. But for all the technological breakthroughs, the deals, and the jousting with franchisees, the company’s guiding light has barely changed. Inside a room beyond a corridor stamped with the word “innovate” in block capital letters, the hum of computers and data processing towers is drowned out by a cacophony of test-kitchen staff running trials on secret processes that aim to shave seconds off a Big Mac’s assembly, much like in the old days, when McDonald’s first upended the food industry. “In old-school business logic, the big eats the small,” Easterbrook says. “In the modern day, the fast eats the slow.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Silvia Killingsworth at skillingswo2@bloomberg.net, Max Chafkin

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.