(Bloomberg Opinion) -- At Deutsche Lufthansa AG’s annual meeting on Tuesday, shareholders had every reason to congratulate the management. Europe’s biggest airline reported record sales for 2018 and managed to maintain profit margins in the face of rising fuel costs.

But one investor berated executives for a failing rarely mentioned at past gatherings: a 7 percent increase in the company’s carbon dioxide emissions.

Moritz Leiner, a representative of the Association of Ethical Shareholders Germany, urged Lufthansa to reconsider its climate-change policy, pointing out that the company operates four daily flights from Munich to Nuremberg, two cities that are only a two-hour drive apart.

He has a point, and it’s worth asking whether cutting back on air travel would actually make sense. Criticisms like Leiner’s are popping up increasingly often – even though airlines are exempt from the Paris Agreement on climate change and the industry accounts for just 3.6 percent of Europe’s CO2 emissions.

Air travel is growing fast. According to this year’s European Aviation Environmental Report, the number of flights in and out of the European Economic Area increased by 8 percent between 2014 and 2017. The figure is expected to grow by a further 40 percent between 2017 and 2040. Add to that the explosive growth in aviation emissions outside the EEA – they more than doubled between 1990 and 2017 – and the industry looks like a big threat to the environment. All the more so because regulators’ efforts to reduce pollution from road transport are stalling: since 2014, the carbon footprint of new cars has remained relatively stable.

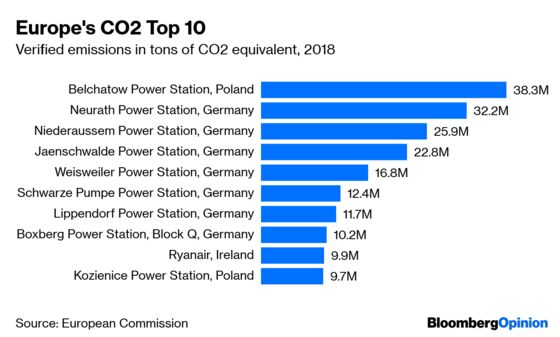

Last month, the European Union’s emissions registry identified budget carrier Ryanair Holdings Plc, whose CEO once described climate change as “complete and utter rubbish,” as the ninth-biggest emitter of CO2 in the EU last year. The others in the top 10 were all coal-fired power plants. The airline alone produced about a quarter as much CO2 last year as the world’s biggest lignite-burning power station in Belchatow, Poland.

In German and other northern European languages, a word already exists to describe what environmentally-conscious people feel about flying. The German flugscham, the Swedish flygskam and the Dutch vliegschaamte translate as “flight shame.” In Sweden, it already appears to be affecting airports’ business as people adjust their travel plans. Other European countries with strong environmental movements, such as Germany and the Netherlands, will likely fall in line.

But what could government and the industry do? The idea of a Europe-wide air travel tax has been mooted by the Dutch and Belgian administrations. It wouldn’t be impossible for the EU to end the tax exemption aviation fuel enjoys, or start charging value-added tax on tickets.

And that would only be a first step: Airlines should look carefully at how regulators have forced carmakers to innovate at the expense of their traditional business models. Similar measures, like stricter emissions standards that would force carriers to use more expensive synthetic fuels, could be in store for the airline industry as it loses its glamour and its aura of national prestige.

Eliminating short-haul flights, which produce more CO2 per traveler than road transportation and don’t save people much time given the waits at airports, would be an obvious way for airlines to reduce their emissions. It’s not enough simply to buy more fuel-efficient planes and to cram passengers in until their knees reach their chins.

Both customers’ growing environmental awareness and the threat of new taxes and regulation should get airlines to think beyond the International Civil Aviation Organization’s current plan to freeze the industry’s emissions at 2020 levels.

Curbing air travel wouldn’t just have climate benefits. The incredible ease of travel in recent years has made cities, especially popular tourist destinations, more similar than they used to be. The growing uniformity and locals’ unhappiness with the tourist hordes are direct consequences of cheap flights. On one hand, they allow more people to see more of the world; on the other, they ruin the experience for these same people and lead to the creation of cheap cardboard versions of major cultures, made especially for low-engagement tourists.

As for business travel, companies should be rethinking their requirements in an era of cheap bandwidth. With 5G mobile communications about to arrive, most business will soon be possible to transact from anywhere. Flying on business should be seen as a luxury.

I, for one, would welcome a world in which air travel would require more investment than today, making people more aware of physical distances and more appreciative of the differences between places. Instant travel as a cheap commodity isn’t people’s natural right: It has only existed for about three decades. Its impact on climate could be a good starting point for some lifestyle rethinking.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.