Yield-Curve Inversion May Speed Up the Dash for Cash

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Imagine these two investment choices: three-month debt that offers a 2.35 percent annualized yield, or 10-year obligations that yield 2.68 percent. Which is the best option?

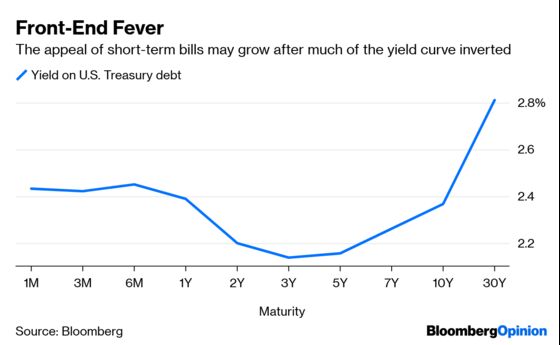

That might be a tough call. This might be easier: three months for 2.42 percent, or 10 years for 2.39 percent?

Denizens of the $15.8 trillion Treasury market probably see where this is going. Those are the prevailing yield levels of three-month bills and 10-year notes at the start of 2019 and now. That part of the curve first inverted a week ago, raising the specter of a future recession and calling into question when the Federal Reserve will cut short-term interest rates. Investors have been on a bond-buying spree ever since, adjusting to the new reality of dovish central banks and potentially slowing global growth. In Europe and Japan, negative-yielding debt is the reality once more.

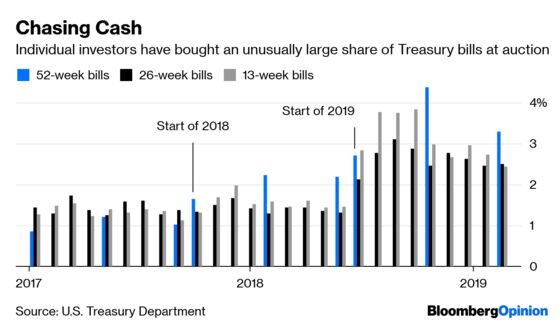

Yet largely unnoticed during the first quarter is the extent to which individual investors have flocked to shorter-dated Treasuries, enticed by the highest returns in more than a decade on what effectively amounts to cash. The group, which also includes partnerships, personal trusts, estates, nonprofit organizations and foundations, purchased $39 billion of bills at auctions in January and February, the most since at least 2009.

Of course, bill auctions have also ballooned in size as the Treasury Department grapples with growing budget deficits. But even on a relative basis, individuals are making a statement. At the Jan. 22 auction of 13-week (or three-month) bills, for instance, they took 3.84 percent of the $42 billion sale, the largest share in eight years. One week later, they bought 4.4 percent of the Treasury’s 52-week bill auction, the second-highest allotment of this cycle. (The percentages are small because money-market funds, along with brokers and dealers, make up the overwhelming majority of T-bill buyers.)

It stands to reason that with significant portions of the yield curve inverted, individuals will at least keep up their pace of T-bill purchases, if not buy more. Of course, inversions happen for a reason. Traders are pricing in at least one Fed cut by the end of the year, which, if that happens, would leave bill buyers reinvesting at lower interest rates. If policy makers drop rates multiple times over the next few years, five-year notes yielding 2.2 percent will have looked like a steal (not to mention they’d surge in price).

That’s part of the reason the core recommendation of interest-rate strategists at FTN Financial Capital Markets is to create a “barbell” portfolio. It combines, for instance, Treasuries maturing in one year, six years and eight years rather than just buying five-year notes outright. “Across four rate scenarios that run from cuts of 50bp to a 50bp hike within 12 months, a 1s/6s/8s approach works with a horizon through the end of this year,” FTN’s Jim Vogel wrote.

It’s basically market consensus at this point that the Fed has lifted interest rates as high as it will go this cycle. I’m not so convinced that officials will soon be lowering rates, but either way, it feels like now’s the time to make one last dash for cash. It wasn’t so long ago that Robinhood Financial LLC caught Wall Street’s attention by seeking to disrupt the traditional bank account with what effectively amounted to a money market fund (it ran into some roadblocks). For now, generic savings accounts from a number of banks still offer rates around the fed funds target range of 2.25 percent to 2.5 percent. Some rates on certificates of deposit are just as high as yields on 30-year Treasuries.

In other words, there are any number of ways for individual investors to get into cash-like assets while short-term rates stay where they are. Purchasing Treasury bills directly isn’t for all mom-and-pop buyers, though with equities not far from record highs, it makes sense that entities like personal trusts and foundations would consider wading into the auction market to cut back on risk.

That sort of thinking will remain top-of-mind as long as the yield curve stays inverted and debate over recession risk intensifies. It just takes another market disruption like the final months of 2018 for cash to rule everything around the bond markets once more.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.