(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Russia has rarely gotten a chance to elect its pantheon: Heroes have often been imposed on it from above in fits of historical revisionism and through propaganda. Recently, however, Russians have been allowed to pick the names of revered compatriots for the country’s 47 important airports. The popular vote, which ended on Tuesday, wasn’t free from government tampering, but it produced a surprising list that shows ordinary Russians tend to be apolitical and quite propaganda-resistant – but also culturally indifferent.

The idea of the airport renaming campaign belonged to Metropolitan Tikhon, a senior Russian Orthodox priest who has been called President Vladimir Putin’s confessor. It was backed by Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky, who has spearheaded Putin’s drive to create a new national ideology for modern Russia, and a number of Kremlin-backed non-governmental organizations. The Public Chamber, a body set up by Putin to maintain ties between the Kremlin and a tame “civil society,” ran the vote.

These origins hardly promised a free expression of popular will, and indeed, the short lists of three names for each airport weren’t picked in a transparent way. One notable instance in which a genuine grassroots initiative was ignored occurred in the big Siberian city of Omsk, where rock musician Yegor Letov didn’t make the short list despite the explicit support of thousands of people (some 27,000 signed a petition to put Letov on the list).

The punk rocker, who was born in Omsk and died there in 2008, was one of the heroes to my generation of Russians. Naming the airport after him would be no less logical than Liverpool’s choice in favor of John Lennon. Never accepted by the Soviet or post-Soviet establishment, he sang, unforgettably:

Voluntarily exiled to the basement,

Doomed ahead of time to utter failure,

I killed the state in myself.

It’s likely that the name of Josef Stalin was crossed off before the short list stage, too. “A lot of talk when we started this project was about Stalin: What if Stalin pops out now? What are we going to do? Stalin didn’t pop out anywhere,” said Public Chamber Secretary Valery Fadeev. That outcome is unlikely to be organic. During the previous attempt to form a Russian national pantheon by popular vote, in 2008, Stalin made the top three.

Despite the likely early stage tampering, almost 5.4 million people voted for the short lists, both online and offline, at airports and train stations. Everywhere except the southern city of Astrakhan the winner of the online vote prevailed.

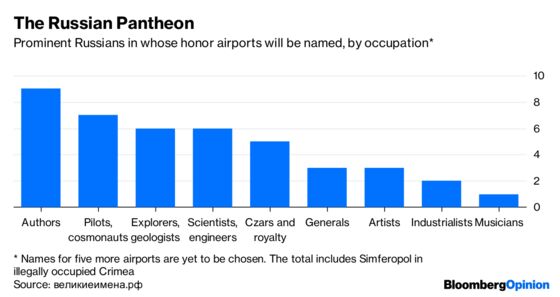

Perhaps the most important result is that Russians’ preferences turned out to be distinctly non-martial. General Dmitry Karbyshev, tortured to death by the Nazis in 1945, won in Omsk – but he’s a martyr rather than a conquering hero. Apart from Karbyshev, only two generals – Alexander Suvorov, who never lost a battle in the 18th century, and Nikolai Muravyov-Amursky, governor of Eastern Siberia in the 19th century – were picked.

Most of the choices reflect a natural leaning toward prominent locals, regardless of their nationwide fame. The oil cities of Siberia and Tatarstan on the Volga picked the Soviet geologists and managers who explored the regions’ hydrocarbon riches. Courageous pilots, explorers and cosmonauts were popular; even those of them who died in crashes weren’t considered unlucky patrons for airports.

Czars – Peter the Great and Catherine the Great – got a lot of votes, reflecting both their glorification in the late Soviet years and the post-Soviet tendency to hark back to Russia’s imperial greatness. The last czar, Nicholas II, won in Murmansk thanks to a campaign legislator Natalya Poklonskaya, who pointed out that Nicholas’s top rival, Arctic explorer Ivan Papanin, had also been a sadistic chief of the early Soviet secret police in Crimea who personally executed “enemies of the people.”

Empress Elizabeth triumphed in Kaliningrad, formerly the East Prussian city of Koenigsberg, which the empress briefly won for Russia in the 18th century; she held off the city’s most famous native son, and her contemporary, the philosopher Immanuel Kant, after a vicious campaign against him by local “patriots.” A statue of the great German was defaced in the city; he ended up with just 25 percent of the vote to Elizabeth’s 33 percent.

Poets and authors make up the biggest group of winners, and Mikhail Lermontov, Russia’s second most beloved poet after Alexander Pushkin, was the biggest vote-getter, garnering the support of 367,681 in the Caucasus, not far from where Lermontov died in a duel. Pushkin’s name went to Moscow’s biggest airport, Sheremetyevo.

These choices largely show healthy preferences for local heroes, people of courage and larger-than-life figures – like Pushkin or Peter the Great – who have transcended the changes in propaganda lines. But they also show the disappointing degree to which the great Russian culture, the country’s biggest claim to the world’s respect, is irrelevant today. Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Kazimir Malevich, Pavel Filonov, Pyotr Tchaikovsky, Igor Stravinsky – none of these greats made short lists anywhere.

Russia’s corps of heroes as formed by the airport vote reflects a peace-loving, pedestrian country with strong local identities. That’s not the Russia of today’s news stories – but perhaps the Russia of today’s public opinion polls, which show a growing disconnect between the people and their government and a diminishing trust in the propaganda pushed by national television. It’s a gray country that’s not too proud of itself.

Even though Putin will make the final renaming decisions, including on airports where winners weren’t picked or the same patrons won as elsewhere, this Russia clearly resists the imposition of any single ideology. As in late Soviet times, Russians are killing the state in themselves. Though there will be no Letov airport, the rocker may still have the last word with his 1988 song.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Therese Raphael at traphael4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European politics and business. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.