What If Google and the Government Merged?

But tech’s long boom may finally be running into some constraints. For the big companies, the constraint is political.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- My colleague Conor Sen recently made a bold prediction: Government will be the driver of the U.S. economy in coming decades. The era of Silicon Valley will end, supplanted by the imperatives of fighting climate change and competing with China.

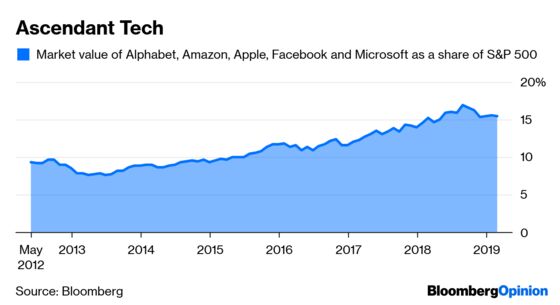

This would be a momentous change. The biggest tech companies — Amazon.com, Apple Inc., Facebook Inc., Google (Alphabet Inc.) and (a bit surprisingly) Microsoft Corp. — have increasingly dominated both the headlines and the U.S. stock market:

Many speculated that online network effects would lead these companies to command private industry in ways that none had before. Imagine Amazon handling all shopping needs, Facebook all social media and so on. Meanwhile, the dramatic success of these companies got investors excited about finding the next tech behemoth. They poured money into businesses such as Uber Technologies, Lyft, Snap Inc., Tesla Motors and WeWork, igniting a second technology boom and sending talent streaming into Silicon Valley, New York City, Seattle and a few other hubs.

But tech’s long boom may finally be running into some constraints. For the big companies, the constraint is political: The increased power of a few seemingly unaccountable giants has renewed an interest in antitrust. People are worried about Amazon’s hardball negotiations with cities, Facebook’s supposed violations of privacy and tolerance of fake news, and/or Google’s alleged bias, as well as these companies’ ability to squash smaller competitors.

In keeping with this sentiment, Senator Elizabeth Warren recently unveiled a plan to break up and/or regulate large tech companies, declaring that these businesses have become so systemically important to the economy that they should be treated as public utilities. In addition to unwinding large tech mergers — for example, forcing Facebook to spin off Instagram and WhatsApp — she proposed heavily regulating Google’s search engine. She would also force Amazon to spin off units that sell products on its platform, preventing the e-commerce giant from competing against its third-party users.

For newer tech companies, the constraints are more practical — there may simply not be room for any more gods in the big tech pantheon. Uber and Lyft are preparing monster IPOs, but they still consistently fail to turn a profit, possibly because of a basic inability to protect themselves from competition. Snap hasn’t even been able to log positive cash flow from operations, meaning it’s still being kept afloat by investor dollars despite being a public company. Tesla has the chance to become one of the world’s giant car companies, but might spend too much money and force itself into bankruptcy. And Netflix is looking less like a platform and more like a conventional movie and television studio company.

Meanwhile, if someone is about to produce another consumer technology on par with computers, the internet, the smartphone, and social media, it’s not apparent what that will be. So-called artificial intelligence is the hot new thing, but it’s more of a back-end technology that makes other applications work more effectively — in other words, not subject to the same kind of strong network effects that give Amazon, Google, and Facebook their dominance. AI can help drive productivity improvements, but might not deliver the stock returns investors have become used to.

So while things are still very uncertain, there are good reasons to believe in Sen’s thesis that information technology won’t be the economic engine it once was — at least not for investors, and perhaps not for the broader economy, either. But the assumption that government will take tech’s place has some problems. All the big important things that government might want to do over the next decade involve a significant amount of technology.

Consider the fight against climate change. The most urgent tasks in creating a carbon-free economy, both in the U.S. and abroad, involve technology and innovation. These include producing better batteries and other forms of energy storage, transmitting electricity from place to place without big energy losses, finding ways to make cement and heat homes without releasing carbon, and developing ways to capture carbon cheaply from the air. Government research can and should help achieve breakthroughs in those areas, but much of the work of making the technologies cheap, practical, and ubiquitous can best be accomplished by the private sector. So expect an increase in government subsidies, public-private partnerships, and infrastructure contracts in the green energy sector.

The other major government imperative is the burgeoning high-tech rivalry with China. Much of this competition will be in the AI field: The country that can develop better machine learning systems will have a natural advantage in networked and precision weaponry, cyberwarfare, espionage and a number of other strategically important areas. In this new space race, the U.S. probably won’t be able to afford demolishing the pools of talent, capital, and technology represented by its big companies. Google, for example, with its world-leading Google Brain project, as well as Amazon Web Services, will become more important to national security.

So one distinct possibility is that big tech won’t be supplanted by government — instead, the two will merge. Large tech companies will be able to keep their dominant positions in exchange for greater regulation and greater cooperation with the government in the race against China and the fight to save the climate. Just as Ford and General Motors became arms of the U.S. war effort in World War II and IBM helped out during the Cold War, Google, Amazon, and other modern cutting-edge companies may become closer to the government.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Whitehouse at mwhitehouse1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.