Productivity Is Way Up. Are You Paying Attention, Fed?

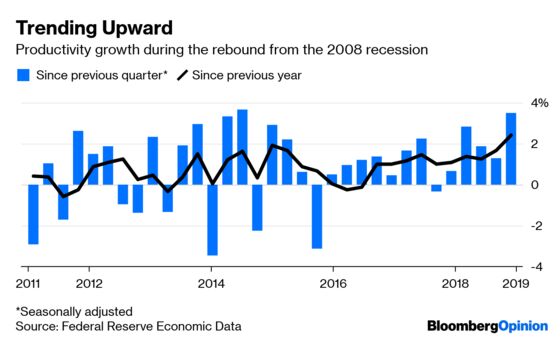

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Productivity rose by a blistering 3.6 percent last quarter. Its growth on a year-over-year basis is the fastest since 2010. That’s a good reason for the Fed to keep resisting the temptation to raise interest rates and to actually consider lowering them.

Soaring productivity could solve a puzzle that’s been vexing the Fed for years: why inflation remains stubbornly low amid brisk economic growth.

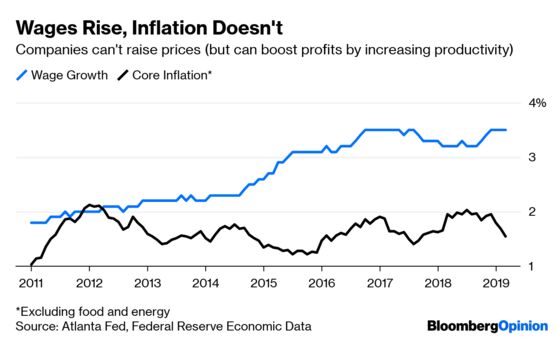

By traditional measures, the strong U.S. economy has produced so many jobs that companies are struggling to find workers. Tight labor markets like this one usually translate into higher wages, as they have, modestly but unmistakably, during the recovery from the 2008 financial crisis.

The Fed fears that those higher wages will fuel too much inflation as employers try to recoup their higher costs by raising prices — unless those higher wages are supported by higher worker productivity. More efficient workers would keep profit margins healthy even as wages rise. Healthy profit margins induce companies to fight for greater market share and the resulting competition should keep prices down despite the tight labor market.

If that’s happening now, then low inflation isn’t caused by transitory factors, as the Fed has claimed lately. It would instead be the result of rising productivity and could remain low for as long as the productivity boom continues. Fed officials like Richard Clarida and Charles Evans are right that the persistent failure of inflation to reach the traditional 2 percent target supposedly needed to sustain growth is more worrisome than the threat of too much wage and price growth.

Indeed, the Fed needs to be careful. Economists tend to welcome productivity growth as manna from heaven because they consider it so hard to stimulate with monetary or fiscal tools. Long-term productivity improvements can be supported by structural developments like educational advances or higher levels of investment, the conventional wisdom asserts, but there is nothing that policymakers can do in the short term to affect it.

That assessment appears to be wrong. It relies on an assumption that business managers will always prefer to focus relentlessly on cutting costs, and will be hesitant, especially in tough times, to hire new workers or to invest in new equipment and experiment with new business practices. Heavy investments in worker training are just not considered.

It takes a tight labor market to change this type of thinking. Instead of selecting the best workers from a huge pool of applicants, companies competing for workers are forced to take what they can get. Eventually, companies accept that this might not be so bad if they invest in improving skills. Those investments increase productivity.

At the same time, the tight labor market encourages managers to turn their attention to labor-saving technology. It’s widely assumed that automation will drive out workers, but often it’s a shortage of workers that drives automation.

Thus policies that keep labor markets tight can sustain new business norms, encouraging innovative practices to increase production with the limited workforce available.

Tight labor markets thus fuel an acceleration in productivity. Slowing the economy risks choking off this process and leaving potential gains on the table. The Fed should worry at least as much about that peril as about keeping inflation contained.

If growth is fueled by the tight labor markets that keep productivity growing, higher interest rates would harm workers and employers without doing much to restrain inflation.

Tight labor markets can’t push up productivity indefinitely. There’s a limit to how much managers can squeeze out of workers. The well of labor-saving innovations will eventually run dry. Runway inflation could then become a problem.

But there’s no sign that the U.S. is nearing that danger zone. The business potential of big data seems far from being maximized, to say nothing of developments in artificial intelligence like natural-language processing or autonomous vehicles.

Most importantly, the hard economic data show weak inflation, strong employment growth and booming labor productivity. As long as those fundamentals are strong, the Fed should cheer rather than fear the tight labor market.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jonathan Landman at jlandman4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Karl W. Smith is a former assistant professor of economics at the University of North Carolina's school of government and founder of the blog Modeled Behavior.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.