The Most Important Number of the Week Is $80

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A buzzword has returned to Wall Street: “stagflation.” This is the rare combination of high inflation and low economic growth. The last time the nation experienced stagflation was during the mid-1970s, when OPEC decided to embargo the sale of oil to the U.S., causing prices to quadruple to almost $12 a barrel. It was a shock that consumers couldn’t handle, thrusting the economy into recession.

Although there is no embargo now, disruptions because of the global pandemic have caused supplies to tighten, sending prices higher in a hurry as economies open up again. West Texas Intermediate crude reached $80 a barrel on Friday for the first time since 2014. What’s concerning is that oil prices have now doubled over the past 12 months, something that DataTrek Research says has preceded every U.S. economic downturn since 1970.

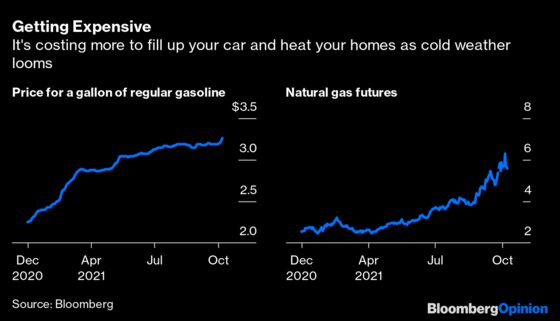

So now investors’ emails are being inundated with research reports from analysts with headlines such as “Will Energy Prices Translate Into Stagflation Risks?” and “Skyrocketing Energy Prices Bring Back Bad 1970s Memories” and “Is Stagflation-Lite the Start of Something More Serious?” I guess the questions have to be asked, but the answers are pretty obvious: most likely not. No doubt surging energy prices will sting. The average price for a gallon of regular-grade gasoline has rocketed 45% this year to $3.26 a gallon. Natural-gas futures have surged 128% since early April. Heating oil is up 69% in 2021.

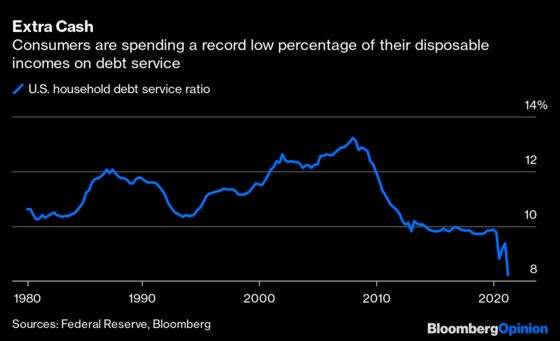

But it’s obvious that consumers and the economy more broadly are better equipped to weather rising energy prices than they were in the 1970s, even with the some 5 million or so Americans who lost their jobs at the start of the pandemic still not back in the workforce. For one, energy makes up a smaller percentage of household expenses. Motor fuels, heating oil, electricity and natural gas make up 4.3% of disposable income, down from more than 7% in the 1970s, according to data compiled by my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Liam Denning. And consumers have more leeway these days when it comes to their expenses. Households are spending a record low 8.23% of their disposable incomes to service their debt, compared with well above 10% heading into the 1980s, Federal Reserve data show.

Although federal government stimulus checks have ended, as have emergency unemployment benefits, consumers have plenty of savings that can be tapped. That stockpile totals more than $2 trillion, according to Bloomberg Economics. As BloombergNEF notes, traffic on the roads is holding up despite the spike in fuel prices and the end of the peak summer driving season.

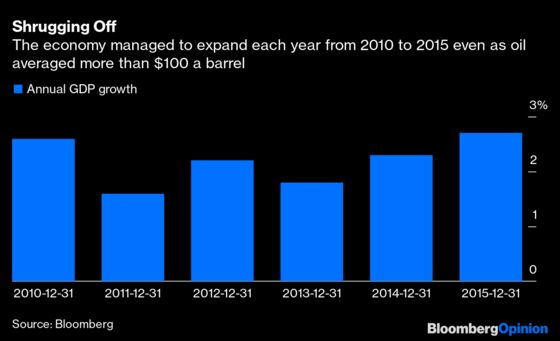

Remember that the economy and consumers did just fine between 2010 and 2015, when oil prices averaged more than $100 a barrel. The strategists at JPMorgan Chase & Co. wrote in a report this week that adjusting for inflation, consumer balance sheets, total oil expenditures, wages and prices of other assets such as housing and equities, even if oil rose to between $130 and $150 a barrel, equity markets and the economy could function well. In fact, they argue that oil is actually cheap at $80 a barrel when considering that all of the major asset classes — bonds, stocks, real estate, etc. — have increased about 50% or more over the last decade, while oil has declined 25%. Here’s how they summed up their views:

Consumer balance sheets are now in a strong position and some reallocation of expenditures towards energy would not set back the economy and equity markets. At the low end of the income range, potential strain from high gas prices could be an issue, but it can easily be addressed with a small fraction of current stimulus plans.

The U.S. and the world learned a lot from the oil shock of the 1970s. The main lesson was that it was time to reduce the economy’s dependence on fossil fuels. Although that transition has been slow, it is happening. Horizon Investments in its “Big Number” report this week pointed out that the “energy intensity” of gross domestic product is half of what it was in the 1970s. It takes 0.43 barrel of oil to produce $1,000 of global GDP compared with nearly 1 barrel of oil to produce the same amount in 1973, they add, citing data from Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

It also helps that the U.S. is not only a net energy exporter now, but it has stockpiled a huge amount of oil in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. Just the mere speculation that the White House might tap those reserves to counter the rise in energy prices sent the price of crude tumbling as much as 2.7% on Wednesday. Sure, the economy is experiencing some level of stagflation, but it’s not like the dark days of the 1970s.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is the Executive Editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global Executive Editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.