(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It worked in the 1990s: The U.S. economy continued to grow strongly for several years even after it showed signs of capacity constraints and low unemployment. The question is whether that can happen again, or whether this cycle is destined to end in a bout of inflation that prompts the Federal Reserve to raise rates and end the party. The answer will depend in large part on whether productivity growth can accelerate as it did a generation ago.

In theory, an economy that’s running hot in the midst of a tight labor market could prompt corporations to invest more and become more productive. That will be difficult to test in the real world, though, because of President Donald Trump’s hostile trade policy and because the Federal Reserve is in no mood to make any sudden changes to their inflation framework.

With the unemployment rate at generational lows, employers are increasingly complaining about labor shortages. A dwindling pool of labor slack combined with above-trend economic growth typically means that faster wage growth and inflation are coming, the types of conditions that lead the Fed to hike interest rates faster. But that environment — low unemployment and reports of labor shortages — occurred in December 1995, as the Federal Reserve noted in its Beige Book report at the time. What followed was a five-year economic boom.

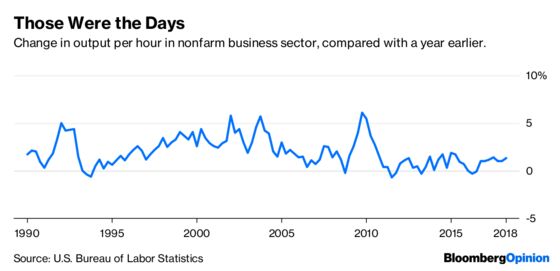

What made that boom possible was productivity growth during 1998 through 2000 that averaged in excess of 3 percent. Workers, aided by the technological revolution of the day, were becoming much more productive, allowing the economy to grow strongly without unwelcome inflation. Productivity growth in recent years has averaged closer to 1 percent, making it much tougher to continue growing quickly without inflation risks emerging.

But technological innovation wasn’t the only story of the late 1990s. Global trade was booming as well. Those were the years that one might call peak globalism, with the passage of Nafta being recent history, the adoption of the European monetary union in 1999, and China getting set to join the World Trade Organization. Increased global trade is a contributor to productivity growth as well. But while that increase in global trade may have contributed to faster productivity growth, it also led to an increase in income inequality, as CEOs benefited from that increase in trade more than workers did.

Obviously, with trade wars escalating today, we shouldn’t expect global trade to drive productivity growth. In fact we could see the decline of trade slowing productivity. So we could lean on the “run the economy hot” approach instead.

Here, the idea is that labor shortages and faster wage growth would make new equipment and technology a more attractive use of capital than hiring workers. Investments here would presumably drive productivity growth higher — think replacing fast food workers with kiosks or self-driving trucks.

But to get that kind of economic environment, we might need to see wage growth, and to some extent inflation, run much hotter than the Federal Reserve seems willing to accept. Rather than wage growth in the 3 percent range, maybe it would need to run more like 6 or 7 percent, which we haven’t had since the 1970s. In a recent speech, Lael Brainard, one of the members of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, reiterated the Fed’s commitment toward its two percent inflation target, and added for emphasis, “Stable inflation expectations is one of the key achievements of central banks in the past several decades, and we would defend it vigorously.”

What we know from experience is that the trade policy you’d want to achieve faster productivity growth is more global trade, and currently the U.S. is moving in the opposite direction. And what seems reasonable to believe from theory is that a tight labor market combined with fast economy growth could lead to a pickup in productivity growth as businesses respond to those conditions by investing more, but it seems unlikely the Fed will allow that to happen either so long as they remain anchored to a 2 percent inflation target.

With birthrates low throughout the developed world and the political environment not being supportive of immigration for the time being, faster productivity growth is critical if economic growth is going to continue at the kind of pace we’ve seen throughout our history. It makes sense to experiment to see if we can do better than we’ve done in the recent past. But over the next few years at least, it doesn’t appear that we will.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Philip Gray at philipgray@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Conor Sen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is a portfolio manager for New River Investments in Atlanta and has been a contributor to the Atlantic and Business Insider.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.