(Bloomberg Opinion) -- From left to right, British politicians have taken one particular issue to heart.

“When it comes to opportunity we won’t entrench the advantages of the fortunate few, we will do everything we can to help anybody,” said Theresa May in her maiden speech as prime minister in July 2016. Since becoming Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn has lambasted “grotesque” disparities that he believes to be the consequence of nearly a decade of Conservative party rule. “We cannot go on creating worse levels of inequality,” he said in a 2017 interview.

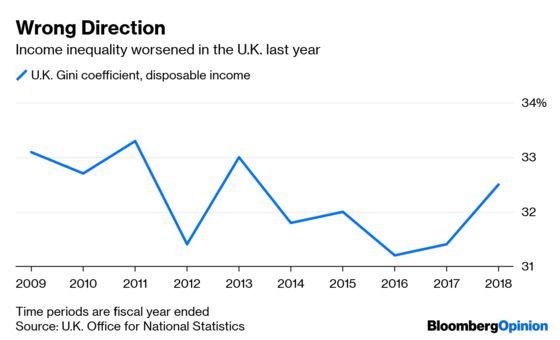

This week, new data from the Office for National Statistics seems to prove that the politicians have chosen a worthy target. Inequality in disposable income, as measured by the Gini coefficient, rose to 32.5 percent in the fiscal year ended in 2018, the largest increase since 2013. The poorest fifth of the population saw its average income fall by 1.6 percent as benefits shrank, while the richest fifth enjoyed a 4.7 percent gain as they received higher wages.

This certainly deserves monitoring, and would be a real concern were the current direction to be sustained. The Resolution Foundation, a think tank, forecasts that the Gini coefficient will increase slightly in the near future as low- to middle-income households encounter particularly weak income growth.

Yet, what happened last year is for now an exception rather than the rule. Income inequality in the U.K. is still slightly lower than it was in 2007, before the financial crisis. Overall, Britain’s welfare state has done pretty well in helping the poor weather the crisis and its immediate aftermath. The ONS has found that in the absence of cash benefits, the Gini coefficient would have been 14.2 percentage points higher in 2014-5.

Of course, it is legitimate to argue that Britain has a problem. The top 1 percent earns around 7 percent of total disposable household income. The Gini coefficient stood at 25 percent in 1978, rose steeply under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and now hovers around 32 percent. This is why Labour is pushing for more radical policy proposals, including restoring sectoral collective bargaining.

Still, the evidence shows that the main form of inequality dogging Britain – much like the rest of Europe – is the one between generations. A report from the Intergenerational Commission found last year that disposable incomes are no higher for millennials who have reached age 30 than they were for the previous generation at the same age. This contrasts, for example, with the steep improvements enjoyed by the baby boomers relative to their own parents. The report also found that while in 2001 those aged between 25 and 34 were consuming the same as 55-64 year-olds, they are now consuming 15 percent less.

Britain's failure to tackle this issue does more than instill a sense of unfairness among its youth. It also breeds resentment and political apathy, which can hamper future economic growth and productivity if it prevents young people from investing in their human capital.

May has done little to address this issue. Last autumn, chancellor Philip Hammond promised “the end of austerity”, as he moved to inject money into the National Health Service, increase the funding of universal credit (the government’s new welfare benefit) and raise the threshold for the personal allowance and higher rate taxpayers. But there was little in the budget for the young, except for an increase in the national living wage for the over-25s, and some more money for homebuilding.

There is hope booming employment levels, which continue to hit record highs, can help the younger generation. But with Brexit taking a toll on the economy, there is a risk that even this rare piece of good news goes into reverse.

A silver lining could, paradoxically, come from the housing market, which is cooling, particularly in London. But it will take time before the South East’s expensive stock of residential property becomes affordable for first-time buyers.

The fight against inequality often puts ideology before evidence. The recent increase in income disparities deserves scrutiny, but pales when compared to the intergenerational gulf which has opened up in Europe over the past few decades. Politicians should have no doubts over where to intervene first.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jennifer Ryan at jryan13@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Ferdinando Giugliano writes columns and editorials on European economics for Bloomberg Opinion. He is also an economics columnist for La Repubblica and was a member of the editorial board of the Financial Times.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.