Trump’s Already Tweeting His Post-Presidency Defense

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- President Donald Trump’s three-tweet sequence on Michael Cohen Thursday morning was different from the usual presidential stream of consciousness. Compact and carefully reasoned, the tweets sound an awful lot like they were written with a lawyer standing at the writer’s shoulder.

Taken together, the tweets signal that Trump and his team are genuinely concerned about the possibility of his being indicted after leaving office — totally separate from any danger of impeachment. That’s significant.

The tweets lay out a three-part defense strategy aimed at fending off a future possible prosecution of the ex-president for campaign finance violations, which Cohen has said he performed at Trump’s direction.

The tweets’ timing tells you that they are responding not only to Cohen’s guilty plea but also to the news that the National Enquirer’s parent company, American Media Inc., has acknowledged paying off Playboy model Karen McDougal with the intention to suppress her story of an affair with Trump and help Trump get elected in 2016. Like the payoff to Stormy Daniels, the adult-film actress who also said she had a sexual relationship Trump, this payoff violated campaign finance law because it was structured to hide the payoff in order to get Trump elected.

What makes the Enquirer admission particularly dangerous for Trump is that it amounts to independent confirmation of Cohen’s account. Essentially, it means Trump can’t defend himself by claiming that Cohen is lying about the payoffs — or their purpose.

The legal strategy in the tweets confirms that Trump isn’t going to say that Cohen lied. Indeed, the three defenses are all highly technical.

They aren’t the kinds of defenses aimed at convincing Republican senators not to impeach. They’re the arguments that defense attorneys propose to prosecutors.

The ideas in the tweets are almost certainly being aimed at the Department of Justice and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York, and they show that Trump is ready to fight this out in court.

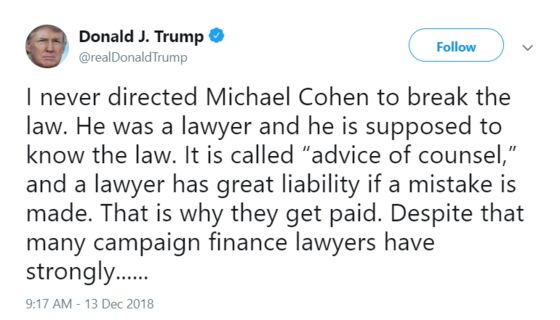

The three defenses can be summarized this way:

- Trump didn’t direct Cohen to commit the violations, because Cohen was Trump’s lawyer and devised the payoff structure on his behalf.

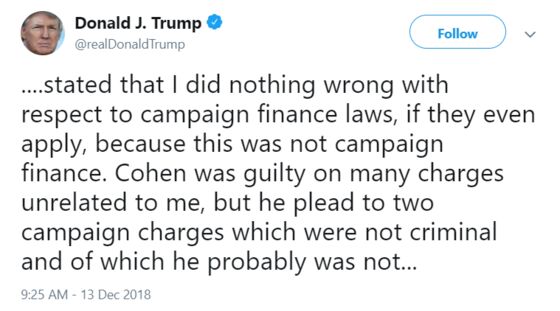

- The payoffs weren’t campaign related — and if they were, the violations were mild enough to be civil violations, not criminal acts.

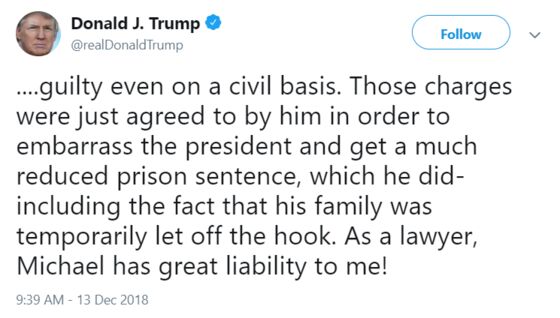

- Cohen’s criminal guilty plea to the campaign violations shouldn’t indicate that the acts were really criminal. Because Cohen was going to prison anyway, he threw in the campaign violation plea as a favor to prosecutors.

Each deserves a closer look — because each represents a hurdle for prosecutors who might want to indict and convict Trump when he leaves office.

Defense 1 is the cleverest. Cohen has testified that he structured the payoffs at Trump’s “direction.” The Southern District prosecutors have said that they accept this formulation.

Ordinarily, the person who directs a crime can be charged with that crime — and ultimately will be, if prosecutors have the capacity to do so. Legally, the one who directs the criminal offense is criminally liable. Morally, prosecutors like to go as high up the chain of command as they can, on the theory that the top person is the most culpable for a course of criminal conduct.

Trump’s tweet insists that “I never directed Michael Cohen to break the law.” The idea is that Cohen “was a lawyer” and was “supposed to know the law.”

Trump is saying he may have told Cohen to pay off Daniels and McDougal, but he didn’t tell him to do it illegally. This is clever because it probably would have been legal for Trump to pay the women directly. If Cohen came up with the structure where he and the Enquirer put out the money first, Trump is saying, then the criminal part was at Cohen’s initiative, not Trump’s.

To defeat this defense, a prosecutor would want to show a judge and jury that Trump knew how Cohen was structuring the payments, and that he either knew it was illegal or at least knew it was aimed at covering up the payoffs.

That may be doable, but it adds work for a future prosecution. And Trump will be able to tell the court and the world that he was misled by his own lawyer — a pretty good public defense.

Defense 2 is more subtle. Trump says the payoffs weren’t “campaign finance” and thus weren’t illegal. Presumably he means to say that he made the payoffs because he wanted to avoid embarrassment, not because he wanted to get elected. The timing makes this doubtful. But it’s worth noting that a prosecutor would have to prove that the payoffs were really connected to getting Trump into office. The say-so of Cohen and the Enquirer might not be enough.

If the acts were campaign-finance related, Trump also says that they were civil, not criminal. That’s a judgment call based on severity. Trump here is mostly trying to convince the prosecutors that they shouldn’t treat the acts as crimes but as civil violations — pay a fine and you’re done.

That brings us to Defense 3: The claim that Cohen didn’t “really” plead guilty to a criminal violation, even though he did. From the prosecutors’ point of view, this is a bit absurd. Cohen did plead guilty to campaign-finance crimes alongside tax evasion and lying to Congress.

The real issue here is that once a subordinate has pleaded guilty to a crime, it’s normal for the prosecutors to indict the principal on criminal charges — not treat the principal’s act as a civil violation.

Trump’s aim here is to say that because Cohen was going to jail anyway, it cost him little to plead guilty to the campaign-finance violations. That’s true. It’s also legally irrelevant. But it might have political weight. It puts the Department of Justice on notice that Trump will say a criminal prosecution of him would be unjustified — despite Cohen’s guilty plea.

Prosecutors will now have to consider these defenses as they decide whether to prepare indictment documents on Trump to be put in the drawer, for possible use in 2021 or 2025.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stacey Shick at sshick@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Feldman is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is a professor of law at Harvard University and was a clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Justice David Souter. His books include “The Three Lives of James Madison: Genius, Partisan, President.”

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.