Trump Puts Supply-Side Economics to Its Final Test

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Corporate tax cuts were basically the last hope for supply-side economics. This economic doctrine, which became popular in the 1980s, holds that taxes distort the economy a great deal, and that cutting taxes therefore produces big gains in growth. Those gains are assumed to eventually result in higher wages for workers, leading some to derisively label the idea as trickle-down economics.

But since the turn of the century, a bevy of tax cuts don’t seem to have had the broad positive effects that supply-siders anticipated. A series of studies has generally concluded that the growth effects of President George W. Bush’s income tax cuts of 2001 and 2003 were small, and the dividend tax cut of 2003 had even less of an impact. That generally fits with economic theory, which holds that the lower the tax rate, the less of an effect cutting it will have — income and dividend taxes had already come down significantly decades earlier, so it makes sense that cutting them even further should have diminishing returns. In any case, earnings for the bulk of Americans stagnated in the 2000s, leaving many with the feeling that the supply-side credo had little to offer.

Corporate tax cuts, however, were the big exception, for three reasons. First, U.S. corporate tax rates were still relatively high before 2017, especially in comparison to other rich countries, most of which had lowered their rates substantially in the 1990s and 2000s. One sign that U.S. rates were too high was that corporate tax revenue wasn’t much higher than in other countries, indicating that American businesses were managing to avoid much of the tax anyway. Second, corporate taxes don’t just affect rich shareholders, but also workers and consumers, meaning that a corporate tax cut wouldn’t only be a cut for the rich. And third, economists generally think that taxes on capital income discourage investment, and thus are more harmful than income taxes, because they reduce the economy’s capital stock in the long run.

Much of that optimism might still be well-placed. The U.S. economy is in a boom right now. Corporate investment is up a bit, though modest compared to earlier eras, which is a small encouraging sign. Unemployment is low. The corporate tax cuts pushed by President Donald Trump might have contributed to this boom — possibly through demand-side fiscal-stimulus effects, but also possibly through the supply-side effects of removing tax distortions.

But one piece hasn’t fallen into place: wages. Even if corporate taxes are raising economic growth and business investment, that new wealth hasn’t yet trickled down to the masses.

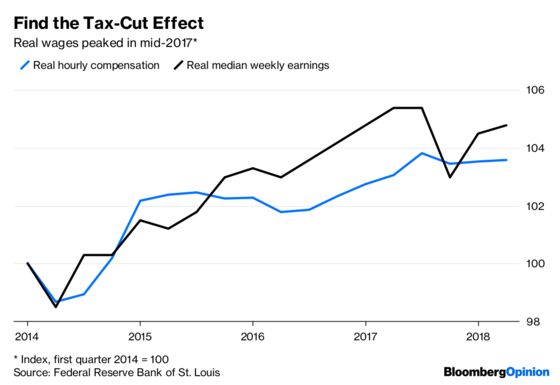

This is apparent just from looking at the behavior of wages since the tax cut was passed at the end of 2017. Two common measures of real wages are still below the peaks they hit in the third quarter of 2017:

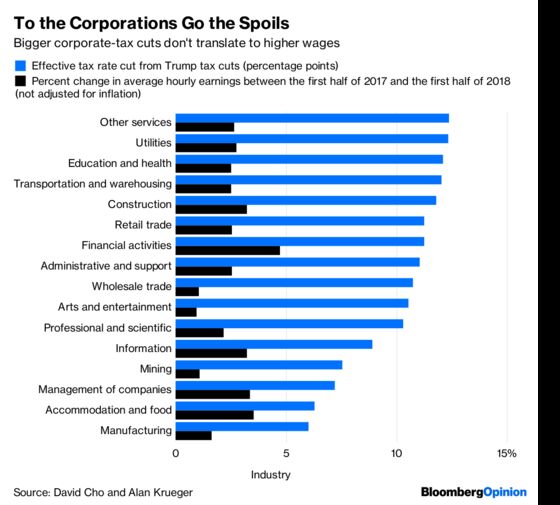

But this is far from the only evidence. Different industries pay different rates of corporate tax, so the tax cut was effectively a different size for each one. Economists David Cho and Alan Krueger compared the size of the effective tax cuts received by various industries with the change in their wages between the first half of 2017 and the first half of 2018. Some industries got bigger tax cuts but had only small wage changes; others, the reverse. Overall, the researchers found no correlation between the two:

It’s still early, of course — it might take time for the increased labor demand from a corporate tax cut to start pushing wages up. But Cho and Krueger also find no correlation between tax cuts and employment changes at the industry level. That’s bad news, since more hiring and tighter labor markets should be the mechanism by which corporate tax cuts raise wages.

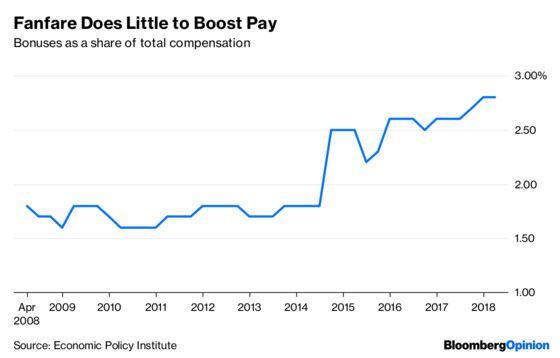

What about those companies that announced bonuses after the tax cut was passed? Sadly, that trend seems to have been exaggerated. Economist Larry Mishel reports that bonuses didn’t add up to a significant increase in total compensation in 2018, implying that the announcements were mostly a publicity move:

So what’s going on? Why isn’t the tax cut raising wages? Perhaps the impact of tax cuts will be felt only over a period of years rather than months. After all, it’s important not to read too much into short-term economic data.

But it also might be the case that the supply-siders are simply wrong. Perhaps those who believed that a substantial amount of the corporate tax cut would go to workers were doing their empirical studies incorrectly, or plugging the wrong numbers into their models. Or maybe U.S. corporations were simply so successful at avoiding taxes before the tax cut that the new lower rate hasn’t really done anything other than to allow them to save money on accountants and lawyers. Either way, if Trump’s corporate tax cuts end up having no observable effect on workers’ pay, it will be the final blow to the supply-side worldview.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.