This Is a Market Only a Contrarian Should Love

Gains are coming when global economic growth is decelerating, forcing central banks to delay normalizing monetary policies.

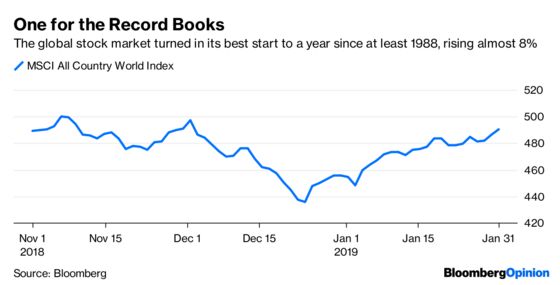

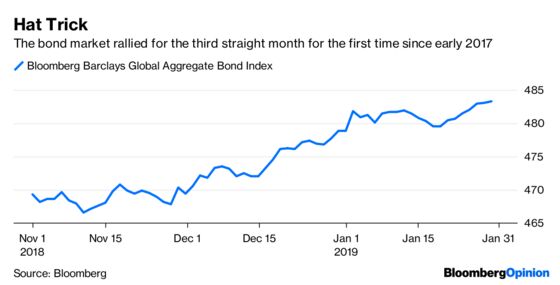

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Market historians are likely to remember January 2019 for years to come. Not only did the S&P 500 Index turn in its best start to a year since 1987 by surging 7.87 percent, but global equities, bonds and commodities all generated positive returns in the same month for the first time since last January. But that’s where the similarities between the moves end, which is too bad.

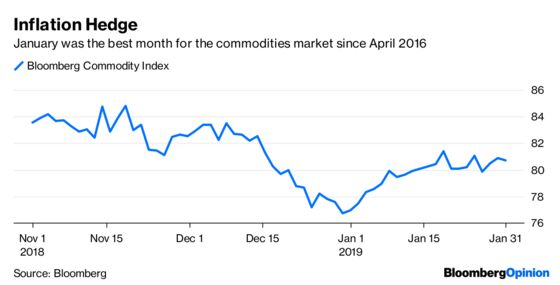

The MSCI All-Country World Index of equities has jumped 7.80 percent, while the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Bond Index was up 0.92 percent through Wednesday and the Bloomberg Commodity Index has surged 5.23 percent. Those just returning from an Elon Musk-sponsored flight to Mars might look at the financial markets and conclude that all is right in the world. In reality, the gains are coming when global economic growth is rapidly decelerating to the point where central bankers are being forced to delay their plans to normalize monetary policies. That’s far different from this time last year, when the buzzwords were global synchronized economic recovery and tighter monetary policy. But as we know, 2018 turned out to be a terrible year for stocks, bonds and commodities, showing that good beginnings don’t always end well. (Everyone remembers what happened in 1987, right?) Will 2019 turn out different? Anything’s possible, but the odds are long given that the recent gains have more to do with relief that the Federal Reserve has had a change of heart and is less likely to cause a recession through excessive interest-rate hikes. But that still leaves a slowing economy no longer supported by either tax cuts or surging corporate profits, which doesn’t engender a lot of confidence.

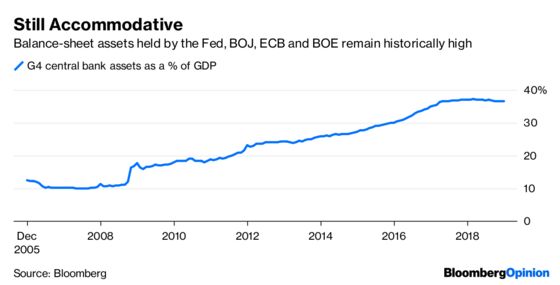

And while the Fed has turned dovish, Chairman Jerome Powell made clear Wednesday that rate hikes would be back on if the economy stays healthy and inflation proves a threat. And it’s not like the end of rate increases is some magic market elixir. “Memo to the bulls: be careful what you wish for,” David Rosenberg, the chief economist and strategist at Gluskin Sheff + Associates, wrote in a Twitter post. The “lag time between the time of the Fed pivot to ease and the recession is typically 6 months.” That’s not all: the Fed is still shrinking its balance sheet, with at least another $500 billion of assets on tap to be jettisoned this year, an amount some economists figure equates to a rate increase of about half a percentage point.

GIVE THE FED A BREAK

Powell and his fellow central bank policy makers have taken a lot of heat for their dovish turn this week. Most of the criticism takes two forms. Either they caved under pressure from President Donald Trump or they are looking to underpin stock prices through some mythical “Fed Put” that only promotes financial excesses rather than supporting the economy. In many cases, these are the same people who criticized the Fed in December for looking past the weakness in stocks and financial assets to boost rates and flag that more were to come. Perhaps it’s better to consider the Fed’s pivot this week as more of a mea culpa. The central bank was too hawkish when it raised interest rates on Dec. 19 for the fourth time in 2018, not because stocks were falling out of bed but because of the impetus for the drop. As December dawned, concerns were rising that the global economy was in trouble. Oil prices were down about 40 percent since early October amid signs of lower demand. Portions of the Treasury yield curve had inverted, a sign a recession is on the horizon. Inflation expectations had plunged, with the bond market discounting any chance that the top line Consumer Price Index number would exceed the Fed’s 2 percent target any time over seven years. Bianco Research points out that only 16 percent of the world’s 35 biggest economies are producing above average economic momentum. Will Powell’s critics change their tune if the Fed proves nimble enough to engineer a soft landing in the economy?

BOND MARKET GIMMICKS

Largely lost in January’s bond market rally was the fact the world remains awash in debt. The Institute of International Finance figures that the global debt pile is hovering near a record at $244 trillion, which is more than three times the size of the global economy. The big question is, at what point does all that debt start to overwhelm demand? Well, the U.S. government may just have dropped a big hint that point is closer than many realize. A ballooning budget deficit caused the U.S. to more than double its borrowing last year to $1.34 trillion, and predictions are that annual new issuance will range from $1.25 trillion to $1.4 trillion over the next four years. And this month, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin asked the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee, a group of external advisers largely made up of Wall Street firms, to assemble a list of potential new debt securities the government might use to expand its investor base, according to Bloomberg News’s Liz McCormick. The U.S.’s rising borrowing needs, even without factoring in the chance of a recession, “would pose a unique challenge for Treasury over the coming decade,” Beth Hammack, chair of the committee, wrote in a report to Mnuchin. Maybe the Treasury is just being prudent, but it’s a shocking nonetheless that the home world’s reserve currency as well as deepest and liquid bond market feels the need to come up with something new to lure investors.

A BUD FOX MARKET

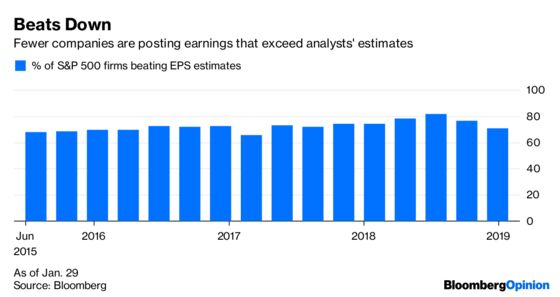

In the classic 1987 movie “Wall Street,” grizzled brokerage executive Lou Mannheim turns to young Bud Fox, who is in the midst of an ethically questionable winning streak, and says, “Enjoy it while it lasts, ‘cause it never does.” That’s sort of the feeling around the stock market these days, which is on a roll despite central bankers around the world who see multiple back clouds on the horizon. Investors certainly can’t be pushing up stocks because they are optimistic about the outlook for earnings. In the U.S., company profits are actually coming in worse relative to analysts’ projections than at any time in almost two years, according to Bloomberg News’s Lu Wang and Sarah Ponczek. But it’s not as if earnings were expected to be up much in the first place, with members of the S&P 500 forecast to report an increase of just 2.2 percent in the first quarter, which is well below the 20 percent or more pace for much of last year. It’s not much better for the second quarter, when profits are expected to rise by a meager 2.4 percent. In that sense, January’s rally only makes much sense if the Fed truly is done boosting interest rates and can engineer a soft landing in the economy — something that is historically rare. “The month leading up to the latest hike was the weakest on record before a pause, so recent strength could be interpreted as a bounce from a deeply oversold condition aided by Fed policy,” Ed Clissold, chief U.S. strategist at Ned Davis Research, wrote in a research note.

CURIOUS COMMODITIES

That leaves the commodities market. It would be easy to peg the rebound in everything from oil to iron ore to sugar on an improving economic outlook, but that would be a bit naïve. For one, the moves have largely been idiosyncratic. Oil has jumped as OPEC and its allies make headway in cutting production, as well as concerns about what turmoil in big producer Venezuela may mean for supplies going forward. Iron ore, the key ingredient used in making steel, is surging after a deadly accident at a Brazil mine run by Vale SA, the world’s No. 1 producer of the raw material. A better explanation for the biggest monthly rally in the Bloomberg Commodity Index since April 2016 may be the Fed. After all, a dovish central bank generally translates into faster inflation, and commodities are a traditional hedge against faster inflation. Breakeven rates on five-year Treasuries — a measure of what bond traders expect the rate of inflation to be over the life of the securities — rose in January by the most since March 2016. The Fed’s pivot has also caused the dollar to weaken, and a weaker dollar generally makes commodities more affordable because they are largely traded in greenbacks. Then there’s the price of gold, which has surged 3 percent this month to about $1,321 an ounce, the highest since May in a sign of demand for haven assets.

TEA LEAVES

The U.S. government will release the monthly jobs report Friday, and by all accounts it should offer no real surprises, even with the government shutdown. The median estimate among economists surveyed by Bloomberg is that the economy added a solid 165,000 jobs in January. The real action is likely to be in the Institute for Supply Management’s monthly manufacturing index. Although economists expect January’s reading to be little changed from December, dropping slightly to 54 from a revised 54.3 in December (readings above 50 denote expansion and those below 50 signal contraction), the risks seem to be to the downside. That’s because similar manufacturing indexes in most major economies have fallen off a cliff, and it’s hard to believe that the U.S. manufacturing sector can continue to hum along in an increasingly globalized economy if its peers are suffering. A similar measure in China has dropped into contraction territory. One for the euro zone is on the verge of following suit, having dropped to 50.5 from more than 60 at the end of 2017. And if signs do emerge that the U.S. manufacturing sector is weakening more than expected, the recent rebound in riskier assets such as stocks and corporate bonds is likely to take a breather.

DON’T MISS

Stock-Picking Contests Are No Way to Pick Stocks: Barry Ritholtz

A Fed Primary Dealer Has Big Balance-Sheet Call: Brian Chappatta

Brexit Leaves U.K. Assets Stranded in Purgatory: Mark Gilbert

The Fed’s Global Fear That Dares Not Speak Its Name: Daniel Moss

The Fed’s Bold Step Toward Main Street: Narayana Kocherlakota

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.