The Real Threat to Your Children Isn't the Momo Challenge

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The “Momo challenge,” the latest iteration of the remarkably persistent teen suicide game scare, is a hoax born of parents’ media illiteracy and anxiety about what kids do online all by themselves. But the issue of internet-inflicted harm to minors is real, and parents need to look out for things other than a spooky, bug-eyed Japanese-designed character.

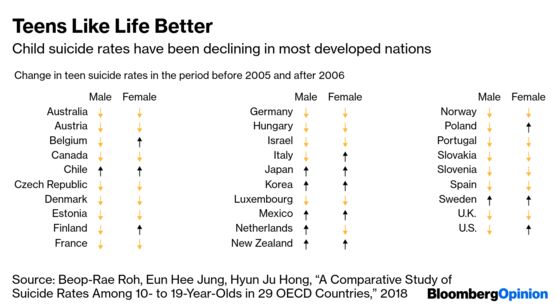

The fact-checkers and data have provided some comfort. Just as in the earlier moral panic caused by the Russian suicide challenge Blue Whale, no one has yet linked a specific death to Momo. Teenage suicide rates have fallen in most developed nations even as internet use increased.

But don't get lulled into a false sense of security. It’s difficult to establish a link between someone’s web history and cause of death. And most comparative studies of teenage suicide rely on the World Health Organization’s mortality database, which isn’t up-to-date enough.

Credible evidence exists linking internet activity and suicide. Swedish researcher Tony Durkee and collaborators reviewed it in a 2011 paper; a number of studies have shown that suicide-related websites and social media groups can push a young person closer to self-inflicted death. New evidence of that, from different countries, keeps emerging.

But it’s likely that by the time a teenager frequents such groups, their parents have already missed something important. There’s a reason there are 10 or more teen suicide attempts for every one completed: Kids want parents and friends to notice something is wrong, and sometimes they use the most drastic way of attracting attention.

Before a teen wants to join an online suicide pact, it is likely that he or she has been bullied. A multitude of studies have established the connection between suicidal thoughts and bullying, whether online or offline.

According to a recent paper by U.S. academics Sameer Hinduja and Justin Patchin, about one in five American middle and high school students reported being subjected to serious degrees of cyberbullying. That tends to lead to “suicidal ideation” – thoughts of killing oneself – though not to the same extent as real-life threats and beatings at school.

Just like with the hyped-up suicide games, it’s next to impossible in most cases to link a teen’s taking of their life to bullying, cyber or otherwise. That doesn’t mean, though, that parents should dismiss the connection as fake.

Then there’s pathological internet use. A link between internet addiction and self-harm or suicidal behavior has been demonstrated repeatedly. The condition, however, is itself a symptom of distress. A 2016 study from South Korea, for example, provides intuitively unsurprising evidence that children of divorced parents, as well as those from both poor and wealthy families subjected to both neglect and competitive pressures, are more likely both to spend all their time on the internet – and get suicidal thoughts.

What’s fundamentally wrong with the hoaxes is that they establish a false link between internet use and suicide where plenty of real links exist. That creates a handy justification for parents to spy on their kids’ online communications. As a parent, though, I know that kind of policing is useless in preventing trouble. Like in the old, pre-internet days, the best way to figure out if a teenager has a problem is to talk regularly and unobtrusively with them; if routine but sincere communication becomes impossible, that is a better warning sign than anything one might find in a chat history.

We often plant the seeds of trouble ourselves at an early age, when, instead of talking or playing, we shut a child up with an iPad. That in itself should be a crime, and not just because of the mind-numbing unboxing videos or disturbing material a kid might find on the web. Last year, a major U.S.-based study showed that more than two hours of screen time a day can damage a child’s cognitive ability. And, quite apart from that, we’re discouraging communication, something we will live to regret by the time we start wondering whether our children are playing an online suicide game.

Parents can be more dangerous to a kid than any version of Momo.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.