(Bloomberg Opinion) -- You can’t say Pedro Sanchez isn’t trying.

The Spanish prime minister is running a minority government, with his Socialist Party holding less than one-quarter of the seats in parliament. Undaunted, he’s trying to cobble together a budget that would raise the deficit targets set by his center-right predecessor Mariano Rajoy.

The measures, which include an increase in social spending and higher taxes on richer individuals and corporations, might not be the best way to strengthen the Spanish economy. But they show at least that it’s possible to offer a left-wing budget while not making a mockery of the European Union’s fiscal rules. Italy, take note.

The Madrid government is targeting a budget deficit of 1.8 per cent of gross domestic product for 2019. True, Rajoy’s People’s Party had envisaged a sharper reduction, to 1.3 percent of GDP. But borrowing levels would still be much lower than this year, when the deficit is forecast to hit 2.7 percent. The European Commission has written to Spain, saying it expected a steeper reduction in the country’s structural deficit, but the difference between what it hoped for and what Madrid plans is only 0.25 percentage points.

There is a strong case for Spain to push harder on the borrowing brakes given how well its economy is doing. Growth has matched or exceeded 3 percent for the past three years, and is expected to hit 2.6 percent in 2018. At 15.2 percent in August, the unemployment rate is still extremely high. But the government had estimated that potential growth was only 1.1 percent this year, so the strong cyclical upswing suggests this would be an ideal time to cut debt substantially.

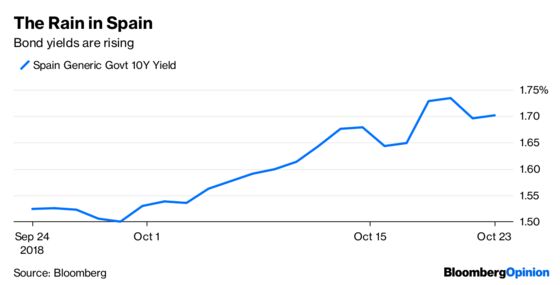

Sanchez’s government isn’t quite doing that. Public debt will fall next year, but only from 97 percent to 95.5 percent of GDP. While that’s lower than many other euro zone countries such as Portugal, Italy and Greece, it’s still much higher than before the sovereign debt crisis. Spain’s bond yields are still low, but they’ve been rising. A prudent government would use the good times to prepare for the next recession. Still, the Sanchez plans aren’t outrageous. Borrowing is expected to fall to 0.4 percent of GDP by 2021, a clear downward path.

The contrast with Italy couldn’t be more stark. In Rome, the anti-establishment administration of the League and the Five Star Movement plans to lift borrowing next year to 2.4 percent of GDP. Claims about the future downward trajectory of the deficit are barely credible. Little wonder that the bond market is freaking out about the plans, which have been rebuked harshly by the European Commission.

The difference between Italy and Spain isn’t so much the motivation of the two governments. Both Madrid and Rome want to help those left behind by the crisis. The Italian government is planning an income-support scheme for the unemployed and the poorly-paid. Spain will increase spending on unemployment and disability benefits and raise the national minimum wage from 736 euros to 900 euros.

Unlike Italy, though, Spain has at least identified those who will lose out from the budget. Income taxes will rise for people earning more than 130,000 euros a year. Business taxes will increase too. Italy, meanwhile, is struggling to choose where to find the money to pay for its handouts. Banks and insurance companies will pay a price, but Rome is reluctant to increase taxes more broadly. The conflicting priorities of Five Star and the League (historically closer to industrialists in Italy’s north) make it harder to devise a coherent economic plan.

The Spanish budget could do more harm than good to the economy, especially by making the country less competitive. But it’s a pretty classic left-wing budget, penalizing corporations and the rich to help pensioners and the poor. From this point of view, it resembles Portugal, where Antonio Costa’s coalition government showed that it’s possible to increase social spending without busting the public finances. What’s happening in Italy is, by contrast, quintessential populism: Promising that everyone will win, when that’s plainly impossible.

Sanchez is still a long way away from getting his budget passed. He has struck a deal with Pablo Iglesias, the leader of Podemos, a far-left party, but still needs to win over a bunch of regionalist parties, which will be far harder to secure. In particular, the Catalans want concessions around their search for independence that Madrid might find impossible to grant.

Still, even if the Socialist prime minister were to fail, his botched budget would offer a useful lesson. For years we’ve heard complaints from the left that the euro zone is a “neo-liberal” project aimed at crushing social spending and helping big business. Spain, like Portugal, shows this is not true. Sanchez’s budget may be neither particularly prudent nor helpful. But it’s a sign that Europe is not all the same.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Ferdinando Giugliano writes columns and editorials on European economics for Bloomberg Opinion. He is also an economics columnist for La Repubblica and was a member of the editorial board of the Financial Times.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.