That Lone Rate Hike Was Probably One Too Many

South Korea’s central bank nudged interest rates up just as activity cooled. There’s little clamor for a repeat.

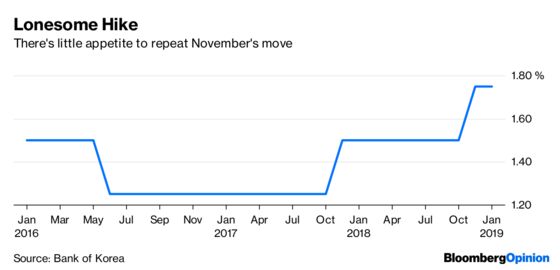

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- South Korea's interest-rate hike late last year looks awfully lonely.

The Bank of Korea's move in November to nudge up its benchmark rate, the first such step in a year, is increasingly seen by economists as a one-time thing. It may also end up being judged an error that's reversed in coming months.

The BOK already displayed little appetite this week to undertake further climbs. The broader regional and world economic currents seem to have caught up with the central bank.

As 2018 drew to a close, South Korea's exports were looking grim and global growth appeared to have peaked. As I wrote in October, any central bank that hadn't begun to withdraw accommodation would find the weather heavy.

The BOK's step, framed as a way to reduce financial imbalances, was either a bold bet that growth would pick up or, at best, not cool significantly. Whatever the basis for altering your stance, you don't want to be shifting to higher rates into a slowdown.

It was telling that the conversation at Thursday's BOK press conference turned to the prospects of monetary easing rather than how to follow November's hike. “Some in the market have flagged the possibility of a rate cut following the Federal Reserve’s turn to a more dovish stance,” Governor Lee Ju-yeol said. “But our current stance is already accommodative, so the BOK doesn’t think now is the time to discuss a rate cut.”

Lee's comments are revealing on a couple of levels. They show how the dominant narrative among central banks has shifted from tightening to, first, plateauing, and then to potential reductions in borrowing costs.

On the “accommodative” point, if policy is still easy then what did one quarter-point adjustment to 1.75 percent get you? Rates are still low. At the time of November’s excursion, Lee cited record household debt and a widening gap between American and South Korean interest rates. I fail to see how a quarter point addresses this in any meaningful way.

On the issue of U.S. rates, it's true that in November the Fed was confidently signaling a December increase in the federal funds rate and the prospect of a few more to come. However, that was a campaign of tightening underway for two years. It wasn't something the Fed decided on the spur of the moment.

It's also true the European Central Bank wrapped up quantitative easing. Again, that was a long process of withdrawal from bond buying that merely had a finale. In Asia, Indonesia lifted rates multiple times and, by late 2018, it had paused.

It's hard to imagine the BOK will stand by November for long. South Korea is one of the world's foremost exporters. Trade figures for the first 20 days of January, released this week, were dire. Overall shipments slid 15 percent from a year ago, and semiconductors plummeted at almost twice that pace. Exports to China slumped 23 percent.

Mistakes happen. It's also important not to overdo the slowdown in global activity. For all the angst about the International Monetary Fund's forecast cuts, the numbers aren't dramatic.

It is appropriate that the conversation in Seoul has shifted. The adventure two months ago should be buried, quietly or otherwise.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Daniel Moss is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian economies. Previously he was executive editor of Bloomberg News for global economics, and has led teams in Asia, Europe and North America.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.