(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The world’s largest market isn’t buying the feel-good narrative that investors have embraced this week with global stocks sitting on the cusp of setting a record high and the riskiest corporate bonds soaring like the world economy is back in synchronized growth mode. But traders in the $5 trillion-a-day foreign-exchange market are flocking to the dollar, yen and Swiss franc, which is a bit odd since those “haven” currencies normally outperform when the outlook is worsening, not improving.

Of course, exchange rates are driven by a seemingly infinite number of variables, but it’s notable that the dollar, yen and franc are the best performers over the past week against a basket of developed-market currencies. The dollar measure is the highest since 2017, while the yen gauge is rising the most since the late 2018 turmoil in global markets. That’s even with speculation rising that the Federal Reserve may need cut interest rates later this year as inflation slows and the Bank of Japan saying on Thursday that it has no intention of raising rates for at least 12 months. It’s not hard to see what has currency traders on the defensive. More and more central banks are expressing concern about the global economic outlook and slower inflation, with the Bank of Canada and Sweden’s Riksbank joining the chorus this week. South Korea, a bellwether for global trade and technology, cast doubt over hopes for a quick rebound in the world economy by reporting on Thursday its biggest contraction of gross domestic product in a decade. China is sending signals that that it might dial back economic support measures, which is a bit concerning given that 3M Co. and Caterpillar Inc. both warned this week about weakening business conditions in the Asian nation. Throw in a budding currency crisis in both Turkey and Argentina, and it’s understandable that foreign-exchange traders might not be ready to join the party.

Perhaps there’s no better indicator that all is not well than global trade. New data on Thursday show volumes are falling at t he fastest pace since the depths of the financial crisis, according to Bloomberg News’s Fergal O’Brien. Calculations by Bloomberg based on the Dutch statistics office’s trade monitor show a 1.9 percent drop in the three months through February compared with the previous three months. That marks the steepest drop since the period through May 2009. Comparing the most recent three months with a year earlier is similarly disappointing. That measure saw a second consecutive decline, also the biggest since 2009.

EMERGING MARKETS TAKE A HIT

The most concerning thing about the currency market is the strength of the dollar, at least as it relates to emerging markets. That’s because every time the greenback makes a sustained move higher, investors get worried borrowers in emerging markets will have a tougher time servicing the trillions in dollar-denominated debt they have taken out in recent years. So it’s little wonder that the MSCI Emerging Markets Index of equities fell as much as 1.15 percent Thursday in its biggest decline since early March. An MSCI index of EM currencies fell the most since early December. Recent history shows such knee-jerk reactions aren’t warranted. Emerging markets weathered a much stronger dollar just fine in 2014, 2016 and 2017. These economies largely restructured their economies after the financial crisis, and much of their trade revenue is in dollars, which actually makes it easier to pay back their dollar-denominated debts. Foreign-exchange reserves for the 12 largest emerging-market economies excluding China have jumped to $3.22 trillion from less than $2 trillion in 2009, data compiled by Bloomberg show. But with global trade slowing, the trend could begin to reverse. For now, though, the bond market seems sanguine. The extra yield investors demand to own emerging-market bonds instead of U.S. Treasuries stands at about 2.88 percentage points, little changed over the past three months and far below the 3.50 percentage point level reached in early January, as measured by the Bloomberg Barclays EM Hard Currency Aggregate Index.

WILL HISTORY REPEAT?

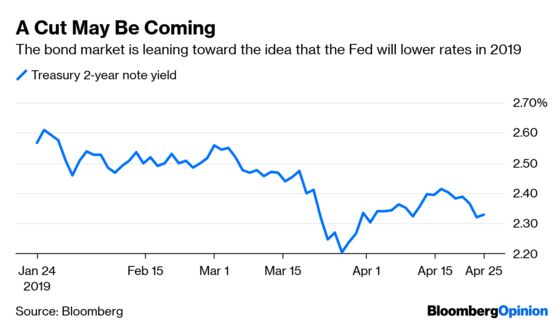

What’s truly extraordinary about the dollar’s renewed strength is that it comes with the futures market moving back toward pricing in a full quarter-point Fed rate cut this year amid speculation the central bank will want to keep inflation from slowing too much and damaging the economic recovery. Lower rates are supposed to damp demand for a currency. There’s no shortage of market participants betting on a repeat of 1998, when the central bank pre-emptively lowered rates to keep events abroad from damaging the U.S. economy, according to Bloomberg News’s Vivien Lou Chen, even though the S&P 500 was rallying and growth was stable. Atr the time, markets were dealing with the Asian financial crisis, Russia’s debt default and the near-collapse of hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management. “You have to pay respect to what the market is pricing in,” Brett Wander, who oversees $28.7 billion as chief investment officer for fixed income at Charles Schwab Investment Management, told Bloomberg News. “A rate cut is a scenario that people have got to consider, even if it’s not the most likely scenario.” Even with markets pricing in a potential Fed rate cut, money markets are still working in the dollar’s favor. Short-term interest rates — which determine the price of currency futures contracts, or forwards — are much higher in the U.S. than in Europe and Japan, according to Bloomberg News’s Katherine Greifeld. The three-month London interbank offered rate in dollars is 2.58 percent, almost 300 basis points above the comparable rate for euros. The difference has almost doubled in the past two years, raising the cost of shorting the greenback for fund managers, Greifeld notes.

ANIMAL SPIRITS ARE LACKING

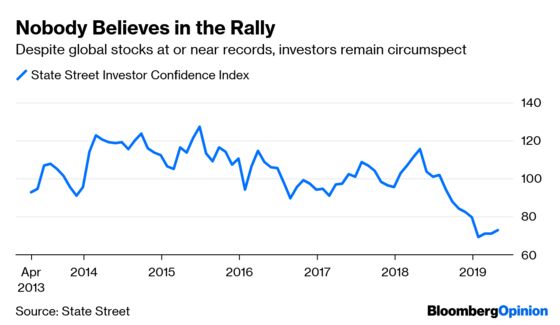

Truth be told, just because stocks are at or back near record highs in an unusually swift rebound from the late 2018 sell-off doesn’t mean animal spirits are running rampant. State Street Global Markets just released its monthly index of investor confidence for April, and the results aren’t encouraging. The measure plunged to an all-time low of 69.4 in January and hasn’t recovered much since, coming in at 72.9 for March. To put those numbers in context, the index only got as low as about 82 during the financial crisis and was above 100 — the level at which investors are neither increasing nor decreasing their long-term allocations to risky assets — as recently as last summer. The measure has authority because unlike survey-based gauges, it’s based on actual trades and covers 15 percent of the world’s tradeable assets. Investors are most pessimistic on the Americas, followed by Europe and then Asia. Cantor Fitzgerald strategist Peter Cecchini embodies the current sentiment. In a week when the S&P 500 Index closed at a record of 2,933.68, Cecchini boosted his year-end target for the benchmark, but only to 2,500 from 2,390, according to Bloomberg News’s Vildana Hajric. For those without a calculator handy, the new forecast represents a 15 percent drop from current levels. “We do not foresee an inflection in U.S. economic growth or S&P earnings growth in the second half as global growth continues to slow and costs rise,” Cecchini said. “We also do not foresee a Fed cut as likely. With slower growth and a Fed that is slow to cut, we think equities will struggle in the second half.” It’s not like Cecchini is some foaming-at-the-mouth bear; he rightly urged investors to buy the dip in January after the big sell-off in late 2018.

COPPER ADDS TO THE BEARISH NARRATIVE

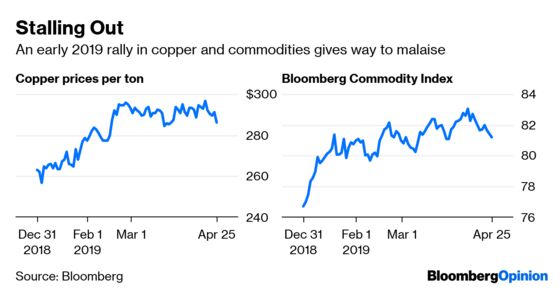

In January and February, the optimists were pointing to the performance of copper, which has a reputation for being a great leading indicator for the global economy given its wide use, as proof that talk of a global synchronized slowdown — and even an imminent recession — were overdone. After all, copper prices had surged 12 percent over the first two months of the year. Since then, though, copper has fallen flat, dropping 3 percent. “There’s no doubt there’s demand for copper around the world, but there’s also the residual effect of the trade impasse between the U.S. and China,” Eli Tesfaye, a senior market strategist at RJO Futures in Chicago, told Bloomberg News. “First you saw it in Germany’s data last week, and now South Korea. The numbers are just not there. The effect is spilling everywhere.” Orders to withdraw copper from the LME have tumbled to 27,600 tons from this year’s high of about 107,000 tons in February, in a sign of weakening demand. And it’s not just copper. After a spurt early in the year, the Bloomberg Commodity Index has struggled to gain any traction, even with the big gains in oil and energy prices. Here, too, the dollar effect is at play. Since many commodities are traded in dollars, a stronger greenback naturally makes owning those raw materials more expensive, tending to damp demand.

TEA LEAVES

The U.S. government’s report on Friday on first-quarter gross domestic product will most likely confirm that market participants were too pessimistic on the economic outlook at the end of last year. The median estimate of economists surveyed by Bloomberg is that gross domestic product expanded at a respectable 2.3 percent rate, a far cry from the recession-like scenario that dominated the narrative as the year began. Some economists are even noting how some indexes that attempt to measure growth in real time are closer to 3 percent, such as the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNow index. The point is that the risk for investors is that the GDP report comes in better than forecast. Nevertheless, the factors supporting that growth may be more ephemeral rather than a sign of sustained momentum, according to Bloomberg News’s Reade Pickert and Katia Dmitrieva. They note that rising inventories and a smaller-than-expected trade gap were among the main forces pushing up GDP estimates for the first three months of 2019. “It’s a good news, bad news story,” said Richard Moody, chief economist at Regions Financial Corp. “If inventories are a big driver of growth in one quarter, then that sets you up for slower growth in subsequent quarters.”

DON’T MISS

Hedge Funds Fail to Deliver What They’re Selling: Barry Ritholtz

How Government Can Make America Grow Again: Gruber and Johnson

Carney’s Replacement Needs to Be Committed: Ferdinando Giugliano

India’s Secret Stimulus Should Be a Warning Sign: Andy Mukherjee

Why Asia’s Central Banks Can’t Pull the Trigger: Daniel Moss

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.