Masa Son Desperately Needs That Second $100 Billion

A more accurate account of how much SoftBank has made from the Vision Fund might come from the money it has actually received.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- SoftBank Group Corp. Chairman Masayoshi Son is in the kind of pickle that even Jamie Dimon can’t get him out of.

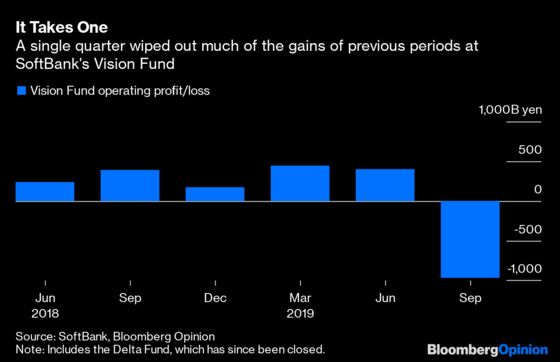

Earnings for the September quarter show just how badly his Vision Fund is performing, and accelerate the need to raise a second incarnation just to keep the money flowing through SoftBank’s books.

While its stake in the $97 billion Vision Fund accounts for less than 15% of SoftBank’s holdings, that investment vehicle made up 53% of operating income last year. Crucially, 68% of that contribution came from unrealized gains on the valuation of investments. In other words, SoftBank is heavily reliant on paper profits.

As a result, the dive in shares of Uber Technologies Inc., Slack Technologies Inc. and Guardant Health Inc. during the three months to Sept. 30, combined with a 498 billion yen ($4.6 billion) write-off on WeWork, weighed not only on the Vision Fund but on the company itself, forcing SoftBank to an operating loss of 704 billion yen, its first in more than a decade. The fund alone lost 970 billion yen for the quarter, which means that it was underwater even before WeWork came along. The only thing that stopped it blowing out further was yet another paper profit: a $2.6 billion gain in the value of its stake in Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.

To really understand what’s going on, however, we need a deeper dive into SoftBank and its relationship with the Vision Fund. Only a handful of the fund’s holdings are in publicly listed shares, whose value can be assessed in real time. What’s more, the biggest contributors to the fund’s gains to date come from buying and flipping two investments: Nvidia Corp. and Flipkart Online Services Pvt. Ironically, its single biggest winner to date — Nvidia — was bought and sold in public stock markets, not through venture investing.

The rest of its shares are private, including marquee unicorns such as Didi Chuxing Inc., ByteDance Ltd., Grab Holdings Inc. and The We Co. — the official name of WeWork. Many got their sky-high valuations because of SoftBank-led investment rounds. Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase & Co., a major backer of WeWork, already learned his lesson. He told CNBC this week, “Just because a valuation prints at a certain level by one investor doesn’t mean it’s the right valuation. That’s not price discovery.”

If Son isn’t listening to Dimon, then let’s hope investors are, because the message is clear: We only know what these shares are worth after they list. Even the bailout and SoftBank’s 83% devaluation of WeWork doesn’t mean the office-rental company is truly worth its new $8 billion number; that’s merely what Son and his team think. The falling price tag on Uber, Slack, Guardant and WeWork all show us to be wary of SoftBank’s ability to correctly value a company. And how the Vision Fund and SoftBank make their money — quarter in and quarter out — is heavily dependent on how much Son thinks his stable of more than 80 companies is worth.

Even if the fund doesn’t make a dime, it’s on the hook for close to $3 billion per year in coupon payments on around $40 billion of preferred shares that pay 7% per year. This cash need is probably what prompted the fund, and not SoftBank, to take out a $4.1 billion three-year loan led by Mizuho Financial Group Inc., JPMorgan, UBS Group AG and Saudi Arabia’s Samba Financial Group.

A more accurate account of how much SoftBank has made from the Vision Fund might come from the money it has actually received. It plays two roles here: SoftBank the investor — just like the Saudi and Abu Dhabi governments — receiving a distribution when the fund sells an investment at a profit; and SoftBank the fund manager, earning a fee for sourcing and executing deals.

All this explains why SoftBank not only wants to raise a second $100 billion fund, but truly needs to: From the fund’s inception through to June 30 this year, it earned $3.2 billion in management performance fees, twice the $1.6 billion it received in distributions as an investor. That distribution is supposed to rise over time as more investments come to market or get acquired, but the decline in publicly traded shares and the cooling mood toward unicorns doesn’t augur well for the future.

With the first Vision Fund tapped out, there’s not a lot of money around to keep pushing up valuations, which in turn drive earnings of both the fund and SoftBank. And with public markets turning sour, hopes of a steady flow of distributions from cashed-out investments are also dimming. That makes fees the most reliable way to keep the machine ticking over. On Thursday, Softbank announced that “preparations for the full-scale launch of SoftBank Vision Fund 2 are underway.” So far that’s been a tough sell as would-be investors, including those who are part of the first fund, balk.

Thankfully for Son, there’s a patron who owes him a favor. Having dodged questions over the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the hands of Saudi agents, and telling Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman that SoftBank wouldn’t abandon him, now seems about the right time to expect a check in the mail. The Saudis can probably afford it. It helps when your own company is about to become the most valuable in the world.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tim Culpan is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. He previously covered technology for Bloomberg News.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.