(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The city of Minneapolis just launched a quiet revolution when the city council voted to abolish single-family zoning. This is an excellent move. Cities around the country should follow suit.

Single-family zoning laws say that the only thing you can build in these areas area are homes designed to accommodate one family. Most of these rules mandate large lot sizes, providing space for lawns, garages and setbacks from the street and neighboring properties. These rules also usually contain height limitations — say, three stories at most. Thus, single-family zoning reduces urban density, limiting the number of people who can live in a city.

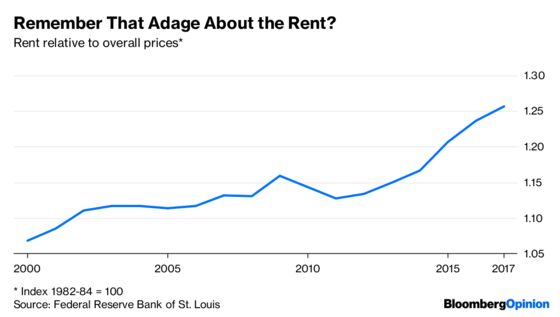

This low density is bad for the U.S. economy. In recent decades, economic activity has become increasingly concentrated in cities. There’s a deep, fundamental reason for that. As manufacturing has become more automated, the drivers of the economy have shifted toward knowledge industries like software, medicine, finance and various high-tech fields. These industries require large concentrations of smart workers to function. But the crowding of highly paid workers into cities is driving up home prices and rents:

If cities fail to accommodate this major economic change, the boom in knowledge-based industries will be self-limiting. Even Google employees in the San Francisco Bay area have trouble affording housing near their workplace, causing the tech giant to look into the possibility of building them small, cheap apartments. Single-family zoning precludes such apartments, and generally limits the supply of housing in dense urban areas, thus increasing costs for both renters and first-time homebuyers. That may be choking off the drivers of U.S. growth.

Single-family zoning is also bad for economic equality. It makes it a lot harder for people of modest means to live in a thriving area, since these people tend only be able to afford apartments, townhouses or other smaller or multifamily dwellings. Blue-collar workers aren’t just being priced out of the country’s increasingly productive cities — they’re being prevented from moving there in search of better opportunities. Urbanist Richard Florida refers to this in his book “The New Urban Crisis.”

There’s also a racial dimension to the inequality that exclusionary zoning creates. Black families, which tend to earn less money, are kept out of white neighborhoods by their inability to afford the sprawling homes that cities mandate be built there. In fact, single-family zoning might have even been invented for just this purpose, as part of a large raft of approaches that cities used to keep higher-earning whites segregated from generally lower-earning black residents after race-based zoning was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1917. Eliminating this zoning is thus one important step on the road to integration.

Denser housing will also be good for the environment, as well as for human safety and happiness. Low-density cities, like the ones the U.S. tends to build, require lots of driving, which increases emissions of carbon and other pollutants, not to mention the risk of crashes. Urban sprawl contributes to habitat loss. In warm, dry states like California, sprawl also raises the risk of property damage and death from wildfires. Long commutes are also a source of unhappiness.

So for a number of reasons — economic growth, racial and class equality, environmental protection and human happiness — cities need to become denser. Minneapolis is leading the way. The city’s new plan even goes beyond simply banning one exclusive form of zoning by eliminating off-street parking requirements for new houses. And it allocates $40 million for subsidizing low-income housing and combating homelessness.

The great hope is that Minneapolis will be the first of a flood of cities to eliminate the exclusionary housing policies of the past century. Cities that make housing more affordable will become more attractive for young knowledge workers, which in turn makes them more attractive for high-value companies. Accommodative housing policy is therefore a better bet for luring investment than offering lavish corporate incentives. Also, creating more places for blue-collar workers to live, and allowing them to move alongside wealthier city residents, will probably be good for the approval ratings of politicians that move against exclusionary zoning.

There’s also hope that national politicians will help prod cities to make the change. U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren has a new plan that would give block grants to cities that eliminate exclusionary zoning. Even Ben Carson, secretary of U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, has suggested similar ideas.

Will allowing density trigger a new wave of white flight to the suburbs, starving cities of resources, as happened in the 1960s and 1970s? There are reasons to think that this time will be different. Crime rates are way down in most U.S. cities, near historic lows. And evidence shows that white Americans are much more willing to move to (and remain in) mixed-race neighborhoods than they were in previous generations.

So onward with urban density and the fight against exclusionary zoning. When the history of the new urban revival is written, Minneapolis may earn pride of place as the first city to make this necessary change.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.