Why Power in the Senate Is Increasingly Imbalanced

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As the stalemate over President Donald Trump’s border wall threatens to lead to another government shutdown, all eyes are on the Senate, where a slim majority of lawmakers continues to support the barrier, even though less than 35 percent of Americans do.

What accounts for this and many other such imbalances in the upper chamber of Congress? The answer, sadly, is that the Senate, which has always given outsize political clout to smaller, rural states, has become increasingly dominated by this constituency. And these days, most of these small states lean conservative, giving them far more power than the Founding Fathers intended or than their relatively smaller share of the population would suggest.

The shift is a natural consequence of a decision made at the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in 1787. The delegates faced an obvious problem: How could they stitch together a republic made up of states of such varying sizes? Although everyone could agree in principle that power in the House of Representatives should be derived from population alone, small states objected to setting up the Senate in the same way.

Their reasoning was understandable. If both the House and Senate derived from population alone, the largest state, Virginia, would have almost 14 times the clout of the smallest, Delaware. In the debates over this issue, delegates from large states and small states traded insults and threats.

The compromise was a House of Representatives derived strictly from population, and a Senate that conferred equal representation on large and small states alike. That meant that even though each decennial census from 1790 onward would alter the number of representatives from each state, the number of senators would always remain the same: two.

The result is that today a voter in the state with the lowest population — Wyoming, with 573,000 people — has approximately 70 times the influence in the Senate as a voter in the largest state, California, where the population is 39.5 million.

Though shocking, it’s unclear whether this imbalance is all that different from the way the Senate has distributed power in the past. Perhaps this has always been the case, and if so, tradition should probably stand. But if the Senate has become increasingly undemocratic in the way it shortchanges large states (and privileges small ones) then reform may be necessary.

Measuring the relative power of large and small states over time is easier said than done, given that the number of states has changed dramatically, and with it, the number of seats in the Senate (for example, the first Senate had only 26 lawmakers).

What has also changed is the relative ranking of states: California was a “small state” at one time, for instance. If we focus on today’s biggest and smallest states, we won’t learn anything about the small-state/large-state dynamics over the entire sweep of the nation’s history.

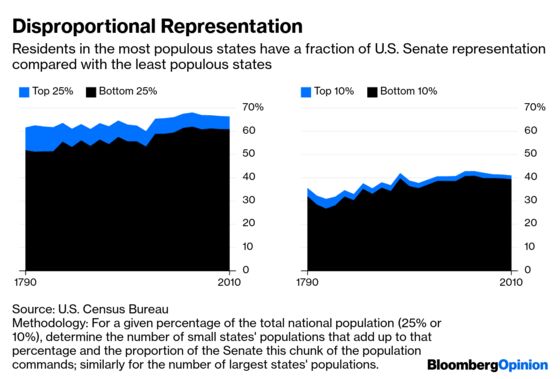

One way of attacking the problem is to choose a certain arbitrary percentage of the total national population: say 25 percent. Then ask a simple question: How many of the nation’s smallest states’ populations add up to that 25 percent — and what proportion of the Senate would this chunk of the population thus command at different points in time?

For example, in 1790 the total population for purposes of representation was a little more than 3.8 million. A quarter of that is slightly more than 950,000, which equaled the combined populations of these six states, listed in ascending size: Delaware, Rhode Island, Georgia, New Hampshire, New Jersey and Connecticut (plus a little of the next largest state, South Carolina). This can then be translated into a percentage of the total seats in the Senate: 51.78 percent.

In other words, in 1790, the 25 percent of the total population that resided in the smallest states controlled 51.78 percent of Senate seats. One can do a similar calculation for a small proportion of the population: say 10 percent. In 1790, this smaller “tranche” of the population — also concentrated in the smallest states — controlled a still staggering 31.96 percent of the Senate.

At the same time, one can flip the question by looking at the largest states. Here the results are very different. In 1790, for instance, the 10 percent of the population concentrated in the largest states controlled only 3.57 percent of the Senate; the top 25 percent controlled a mere 9.81 percent.

This was unequal representation. But in all fairness, this was by design: Small states were supposed to have disproportionate power in the Senate in 1790. If you perform the same calculations every 10 years from 1790 on, a rather interesting pattern emerges.

In the first two decades of the 19th century, the large states got a little more clout in the Senate (and the smaller states lost a bit of their power). This was due to an evening out of the population, reducing the disparity between the biggest and smallest states. Then the tide began to turn in favor of the small states.

Part of this was driven by the rapid-fire admission of a number of new states, many of which started very small, particularly in the West, even if they didn’t stay that way for long. As the population grew, these distortions faded away.

Since around 1900, the smaller states have slowly amassed more power at the expense of the larger states, in part because of the growing concentration of the population along a smaller number of states along the coasts.

The graphs above show that story in full, and while the trends have unfolded at a glacial pace and without dramatic shifts, it is hard to deny that the large states are considerably weaker now than they were in the U.S.’s formative years.

Likewise, the smaller states have definitely amassed more power, though this shift is less dramatic.

In 1790, the 10 percent of the population concentrated in the smallest states had around nine times the number of Senate seats as the 10 percent in the largest states. By 2010, the 10 percent in the smallest states controlled about 23 times the number of Senate seats as a comparable bloc in the most populous states.

While it’s unlikely that we’ll be passing a constitutional amendment to fix the problem, the nation is overdue for a nonpartisan debate over whether there are limits to the extent to which the largest and smaller states can diverge in size.

For example, states once had to meet a certain population threshold in order to gain admission to the union; what if states faced the prospect of losing statehood if they fail to maintain that threshold?

This is not as far-fetched as it may seem. Throughout U.S. history, territories that wished to become states had to reach a certain basic population threshold before being considered. In the opening decades of the 19th century, for example, states generally had to wait until they had 60,000 inhabitants before applying.

By that measure, three states now fall short: Wyoming, Vermont and North Dakota. If they were territories, none would meet the current population threshold and would remain without representation in Congress. (Sorry, Bernie Sanders!)

Another possibility would be to limit the size of big states. Once a state gets too big — I’m looking at you, California and Texas — they would need to split into two, or even more parts, as some Californians have proposed. This, too, would address the problem.

And there is a problem.

What began as a commendable effort to compromise over two centuries ago has introduced a powerful distortion into our system of representation, one that the architects of the Constitution did not anticipate, and most likely, would not have approved of — unless, of course, they were from Delaware.

This actually understates the degree to which this system penalized the largest states: The population totals used here include enslaved persons, who counted as 3/5ths of a person in apportionment totals for the House of Representatives.

There are 435 seats in the House of Representatives.The apportionment population from the 2010 census was 309,183,463, which yields the figure of 710,767 residents per representative.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Max Berley at mberley@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Stephen Mihm, an associate professor of history at the University of Georgia, is a contributor to Bloomberg Opinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.