Europe’s Beloved Roundabout Finally Invades America

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It was late one weekday afternoon in Fishers, an affluent Indianapolis suburb with a lot of offices and retail as well as houses, and the traffic was starting to get irritating. There were long waits at lights. At one intersection, the line of cars waiting to turn left blocked the main traffic lane.

Then I crossed over into Carmel, another affluent suburb with lots of offices and retail as well as houses, and everything changed. Instead of traffic lights, there was roundabout after roundabout after roundabout. There also weren’t any long waits or backups at intersections. I can’t say that I breezed through all of the roundabouts — the signage at the bigger ones was a little confusing for a first-timer — but all the other drivers seemed to know what they were doing. Traffic flowed, but it didn’t flow too fast. When a couple of pedestrians showed up at one roundabout, cars had no trouble stopping for them.

That there were so many roundabouts in Carmel (it has upwards of 100, more than any other city in the U.S.) was not a surprise. I had been alerted to their presence by a former Indianapolitan, and I had gone slightly out of my way during a cross-country road trip last month to experience them. I was a little surprised, though, at how well Carmel’s roundabouts worked. Yes, I’d seen roundabouts function successfully in the U.K., where they were standardized and popularized starting in the 1960s, and elsewhere in Europe. But I figured U.S. drivers, more accustomed than their European peers to being told what to do at intersections by lights and stop signs, would struggle with the snap decision-making they require.

A roundabout works on a simple principle: Cars already in the roundabout get priority over entering vehicles. There are no signals or stop signs. And yes, Americans have struggled a bit with this. “Currently, drivers in the United States appear to use roundabouts less efficiently than models suggest is the case in other countries around the world,” reported the Transportation Research Board of the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine in 2007. But practice clearly helps, and we keep getting more opportunities to hone our roundabouting skills every year!

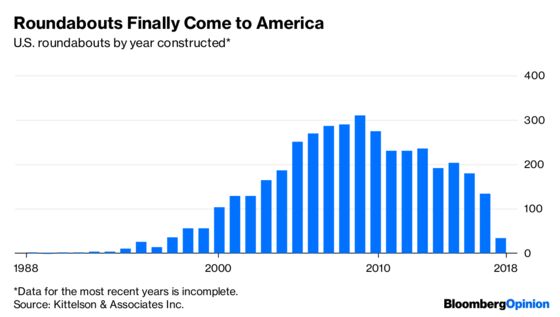

While the dip in roundabout construction after 2009 in the above chart is for real, the result of straitened state and local finances in the wake of the Great Recession, one shouldn’t make too much of the drop over the past couple of years, at least not yet. According to Lee Rodegerdts of the Portland, Oregon, engineering firm of Kittelson & Associates Inc., the keeper of our nation’s roundabout data, there’s something of a time lag in getting new roundabouts into the database. In any case, there are still tons more roundabouts being built in the U.S. now than there were in any decade before the 2000s.

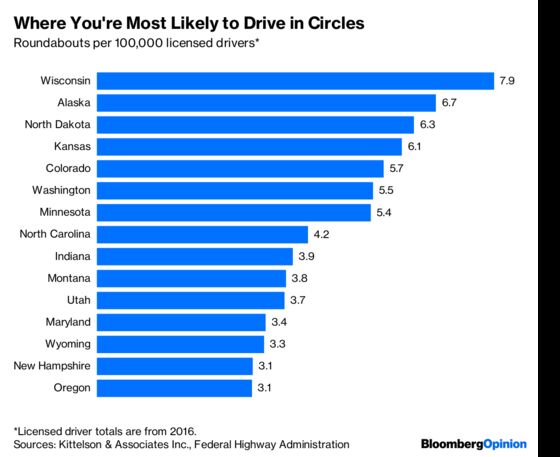

This country is in the midst of a major shift in its built environment and its traffic patterns, then, yet this has attracted only minimal national attention. Maybe that’s because it’s just … roundabouts. But I think it’s also because decisions about road construction are made mainly at the state and local levels and, with the exception of Maryland, the states and cities that have adopted the roundabout with the greatest enthusiasm are all pretty far from the national media’s main bases in New York and Washington. It certainly was news to New York-based me when I encountered roundabouts over the past few weeks in not only Carmel but Muncie, Indiana; Missoula, Montana; Walla Walla, Washington; Bend, Oregon; and even Lafayette, California, the San Francisco suburb where I grew up.

The main safety benefits of roundabouts are that (1) it’s really hard to collide with another car either head-on or perpendicularly in one and (2) they rely on geometry rather than just lights and signs to slow traffic down. I know this mainly because that’s what it says in “Roundabouts: An Informational Guide,” the 2000 report published by the U.S. Department of Transportation that laid out the case for roundabouts and the parameters for designing them and played a big role in the subsequent roundabout boom.

Carmel, where long-time mayor Jim Brainard has made roundabouts a signature of his tenure, got its first one in 1996, but before 2000 there were only a few dozen “modern roundabouts” — as opposed to traffic circles that follow different rules, such as Columbus Circle in New York City and the many circles of Washington, D.C., which aren’t counted in the above charts — nationwide. Now there are more than 4,000, according to the Kittelson & Associates database.

Given the size of the U.S., that’s low compared with many other developed countries. Still, things are changing, and data and expert analysis seem to have brought on the shift. The most prolific source of that data and expert analysis has been Rodegerdts, the lead author of that 2000 report, as well as of the 2007 Transportation Research Board report cited above and 2010’s “Roundabouts: An Informational Guide, Second Edition.” In an email, Rodegerdts cited some other key factors: “In addition to growth that funds the roundabouts, it requires strong leadership, definitely on the public side and ideally on the private side if development is funding the changes.”

Roundabout advocates definitely have to be strong enough to power through some backlash, as there’s usually griping when the things are introduced. In Wisconsin, where the state Department of Transportation has been especially pro-roundabout, some lawmakers have been trying since 2013 to give municipalities veto power over them (the bill hasn’t passed). Truckers complain that some roundabouts aren’t wide enough for them to get through, while neighbors complain because roundabouts take up more space than other intersections. Even roundabout fans acknowledge that they can be problematic for bicycles — the safest way for bikes to traverse them seems to be via the pedestrian crosswalks (or dedicated bike crosswalks), but that’s usually a lot slower than just riding through.

So yes, there are challenges facing our nation that cannot be solved by roundabouts. But in these contentious days, there’s still something encouraging about their spread.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.