(Bloomberg Opinion) -- First, the good news. More white Americans want to live in heavily black neighborhoods. A 2016 paper by the National University of Singapore’s Kwan Ok Lee found that since 1990, neighborhood segregation by race declined. Even better, mixed white-black neighborhoods have tended to stay mixed, instead of resulting in white flight or displacement of black residents. This trend isn’t true in every area of the country, but it’s quite a change from the mid-20th century, when whites fled mixed neighborhoods en masse to more segregated suburbs.

Now for the not-so-good news. A recent investigation by the New York Times confirmed the trend of white people moving into black neighborhoods. But it also found a disturbing pattern. When a neighborhood is diversified by an influx of nonwhite people, the newcomers’ incomes tend to be about average for that neighborhood. But when white people move into a mostly nonwhite neighborhood, their incomes tend to be much higher than the local average.

Although gentrification tends to improve neighborhood amenities, it can also cause difficulties for long-time residents of poor minority communities. Gentrifiers may be more likely to call the police on their neighbors. New retail outlets can change the character of a neighborhood. And most importantly, housing prices tend to rise, putting pressure on those of modest income. The biggest worry related to gentrification is that it will result in displacement.

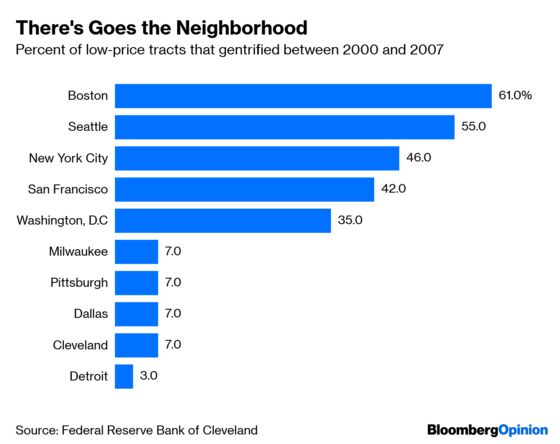

For some low-income residents in the country’s so-called superstar cities, this is the reality. A study by the nonprofit National Community Reinvestment Coalition found that from 2000 through 2013, displacement of long-time residents was heavily concentrated in big cities with strong economies. A 2013 study by Daniel Hartley of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland supports this story:

But overall, gentrification isn't a big source of displacement. Some studies have found no evidence of increased exit of low-income residents from gentrifying neighorhoods. The NCRC study did find about 135,000 black and Hispanic people displaced by gentrification over the 13 years they studied, mostly in the superstar cities like New York and Washington. And they guess that the true number is somewhat larger. But in a country of more than 300 million people, 135,000 is a very small number. Meanwhile, a 2009 study by urban-planning researcher Lance Freeman found that gentrification didn’t decrease neighborhood diversity.

So although gentrification displaces a few low-income minority Americans, this isn’t a widespread phenomenon, and it isn’t leading to re-segregation — if anything, it appears to be modestly reversing the effects of white flight. Of course, rising housing costs are still a burden for those who aren’t displaced, which is part of a more general crisis of affordability in the country’s more desirable cities. And higher rents deter poor minority Americans from moving to economically healthy neighborhoods. The government should be doing all it can to bring down housing costs.

But the phenomenon of gentrification tends to distract urbanists, reporters and policy makers from the bigger problem afflicting American cities — concentrated poverty. Even as a few superstar cities see influxes of well-to-do residents, many more are languishing in neglect and decay.

A 2019 study by the University of Minnesota Law School’s Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity found that for poor Americans, concentration of poverty and local decline were much more common outcomes than gentrification. Since 2000, the study reports, 36.5 million Americans have experienced both local economic decline and an increase in the number of poor people living nearby. It found that the low-income population of economically declining regions has grown by more than 5 million in that time.

Ohio urban planner Jason Segedy is frustrated by the lack of attention to this trend:

Many well-intentioned people … worry so much about the potential downside of urban revitalization, that they are overlooking the far greater challenges of inter-generational poverty, uneven economic growth, disinvestment, abandonment, negative-net-growth urban sprawl, and pervasive and entrenched racial and economic segregation.

Segedy is right. Concentrated poverty, especially in declining towns and cities such as Detroit and Cleveland, is a much bigger problem than gentrification. But because the former is an old, well-known phenomenon while the latter is a newer trend, attention is naturally drawn to the latter. This is dangerous, because excessive worry about the potential harms from gentrification might cause some policy makers to discourage investment in poor minority communities, out of fear of displacement. But discouraging that investment would cause many more problems than it would prevent.

Instead, policy makers should try to manage and alleviate the strains of gentrification, while continuing to vigorously attack concentrated poverty. Policies to encourage investment in poor minority neighborhoods, like the successful Empowerment Zone program that began under President Bill Clinton and expired in 2016, should be maintained and expanded. Just because a problem is old doesn’t mean it can be safely forgotten.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.