Oil's Next Great Deflationary Force: Taxes

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In a commodity business, cost is king. The efficient producer ultimately wins more business and more investment – and that is as true for countries as it is for companies.

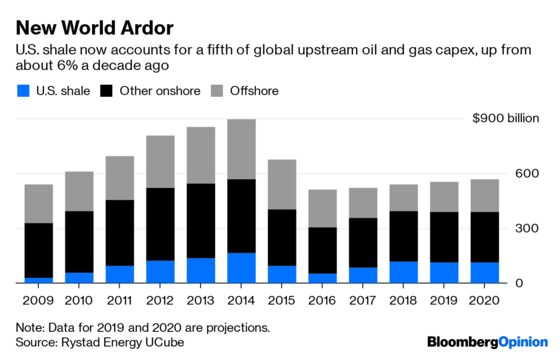

The shale boom, along with slowing energy demand growth in much of the industrialized world, has changed the global oil and gas business. Rising productivity in areas such as the Permian and Appalachian basins has been a deflationary force rippling out across the industry, forcing producers everywhere from Canada’s oil sands to Brazil’s deepwater fields to cut costs.

Similarly, North America has become a magnet for investment, with even such former globetrotters as Chevron Corp. and Exxon Mobil Corp. rediscovering an affinity for home. In parallel, Schlumberger Ltd., a bellwether for upstream spending beyond the U.S., trades around levels reached in the depths of the financial crisis, despite the fact that we are now about three years into a recovery in oil prices.

Oil and gas companies are working, with varying degrees of success, to redefine themselves in the face of this, with a particular focus on keeping costs down. One of those costs is largely out of their hands, except in the sense that they get to choose where they drill: taxation.

In a report published last month, analysts at Morgan Stanley surveyed nine countries, other than the U.S., where oil majors have typically been active. They found that the government’s share of net present value in its remaining resources averages about 63% under current fiscal terms for those countries . The U.S. figure, meanwhile, is just 36%.

Industry griping about harsh fiscal terms is an old sport and one that amounted to little when it was thought that ever more of the world’s supply would migrate to the likes of Saudi Arabia. Only a decade ago, oil majors were signing up to be paid a relative pittance per barrel for the chance to drill in Iraq. Times have changed. OPEC exists pretty much as a mere adjunct of Saudi Arabia at this point, with that country’s latest round of haggling with non-member Russia over production cuts being the latest reminder. And with “peak oil” having morphed into speculation about peak demand, the old assumption that the value of petrostates’ underground hoards would only appreciate over time has been overturned. So just as companies are competing to be the lowest-cost, Morgan Stanley’s analysts point out that there is an incentive for countries to do the same.

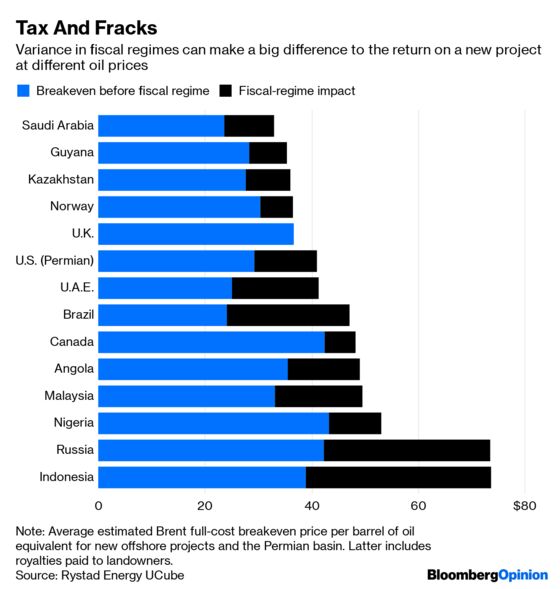

Rystad Energy, a research firm, has calculated breakeven prices for new offshore projects in various countries as well as in the Permian basin, both before and after factoring in the fiscal take.

Some countries have already loosened terms to attract more investment. For example, the U.K. slashed tax rates in 2016 in a bid to stem the slide in oil and gas production. Output in 2018 was 8% higher than in 2015, and Brent crude oil prices had risen 53% in sterling terms, but the government’s overall tax take fell by almost a quarter. In a different way, and at the other end of the spectrum, Saudi Arabia’s reform plans aimed at diversifying the tax base away from oil represents another attempt to effectively reduce the country’s overall breakeven price.

What’s striking about the chart above is that, absent the fiscal impact, the range from low to high in terms of breakeven costs is relatively small at about $20 a barrel, with Saudi Arabia at the low end with sub-$24 and Nigeria up at just over $43. Once you factor in the governments’ take, that range doubles, spanning $33 to almost $74.

The implication is that, just as the shale-led decline in upstream unit costs has been deflationary, fiscal competition between states could add to that effect. Those countries that rely heaviest on oil and gas taxes will, of course, find it hard to loosen up. Equally, though, they will ultimately confront the prospect of rival producers taking a bigger share of a market heading toward a plateau. Barrels left in the ground don’t provide any taxes at all.

The nine countries are Angola, Argentina, Brazil, Egypt, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Nigeria, Norway and Oman. Morgan Stanley used data from Wood Mackenzie.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.