(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Netflix Inc. is such a confounding company.

It is by far the most dominant company in streaming video — and streaming video is plainly the future of television. Its first-quarter results, unveiled last week, show that it’s closing in on a staggering 150 million subscribers. It is available in 190 countries. Its streaming technology and sophisticated use of data are unparalleled in the industry. Chief executive Reed Hastings and chief content officer Ted Sarandos are foresighted leaders who have consistently displayed a knack for making the right moves. Is it any wonder that when Netflix tried to raise $2 billion in the bond market recently, it got $6 billion worth of orders?

On the other hand …

The legacy media companies are preparing to come hard at Netflix, with their own streaming services. The Walt Disney Co. alone will be a fierce new competitor; Disney+, set to launch this fall, is going to bundle its great franchises (Star Wars, Pixar movies) with its fabulous library and the popular content (like the Simpsons) that it got in the Fox deal. Disney and others are taking their content off Netflix.

Then there are the numbers. Netflix is spending insane amounts of money — Variety estimates $15 billion this year — creating shows and movies. It is luring important showrunners like Ryan Murphy and Shonda Rhimes with nine-figure deals. It taps the bond market because it doesn’t have the cash to cover all that spending; indeed, it’s been cash flow negative since 2015. Netflix estimates that its cash flow in 2019 will be (gulp) negative $3.5 billion. As my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Shira Ovide pointed out early this year, its obligations off the charts: “It owes $32 billion in coming years for streaming content, debt repayments and other commitments.” Yikes.

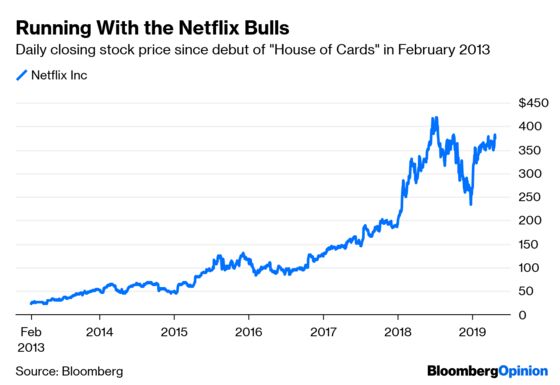

If you’re an investor, how do you think about a company like this — a company that is growing like mad in an important new industry but whose numbers are terrifying? Most investors, of course, have focused on the growth and not the numbers. That’s why Netflix stock has gained about 1,300 percent since it premiered its first important original show, “House of Cards,” in February 2013. And it’s why, of the Wall Street analysts who cover the company, 30 have “buys” on the stock, and only four have “sells,” according to Bloomberg data. Being a Netflix bear isn’t much fun these days.

What prompts these thoughts is a story that caught my eye this week about the most vocal Netflix bear on the Street, Michael Pachter of Wedbush Securities. The story, which was posted on Business Insider, said that in 2017, a Wedbush executive had written a widely distributed internal email calling on the research department to stop following Netflix because Pachter’s bearish call had become “a joke” and “one of the worst in history.” The email’s implication was that Pachter was damaging Wedbush’s credibility — and its brokers’ ability to sell stocks to clients — by staying so stubbornly bearish.

As I quickly learned, the story was, shall we say, overheated. The author of the email wasn’t a significant company executive. As soon as the email circulated, Pachter said, the higher-ups raced to his defense. The broker was given a talking to, and apologized.

Pachter has been a Wedbush securities analyst for 20 years. He’s not one of those people who views all stocks through a negative lens, the way a short-seller might. He told me he has “buys” on lots of stock, including Amazon.com Inc. and Facebook Inc. But with Netflix, he’s never been able to get comfortable with the upbeat growth story because he can’t get past the story the numbers tell.

“I feel like I’m Neo in ‘The Matrix,’” he told me when we spoke the other day. “I can see everything, and I’m baffled why no one else can see it. In fact, it’s shocking to me that everyone doesn’t see it.”

When I asked him how he would define “it,” he replied: “On CNBC recently the host asked me why my price target for Netflix was so low.” (With Netflix stock at $368 a share, Pachter has a $183 price target.)

I said that in order to justify my price target you need $1 billion in improvement in perpetuity. You need 2 billion a year in free cash flow improvement. In order to get there, you need some 300 million subscribers paying $20 a month. I don’t doubt they can do that in a vacuum. But they’re not in a vacuum. What will happen if competitors are charging $7? I know analysts who say that Netflix is spending $15 billion on content, and Disney is “only” spending $4 billion. But Disney’s library has “Frozen” in it. They act as if the library has no value.

I asked him to sketch out the most likely negative scenario. He said that the first sign of trouble will be domestic subscription growth slowing to a crawl. (That’s already started to happen.) Competition from Disney and others will make it hard for Netflix to raise prices. As the business slows, and the stock starts to fall, the debt markets will stop being so friendly to Netflix. That will force the company to cut back its spending on original movies and TV shows. Which will cause viewer defections. Which will make cash even scarcer. Which will make it harder to pay down its debt. “It will be death by 1,000 cuts,” he said.

Needless to say, Netflix bulls don’t believe it will play out the way Pachter envisions. But the smart Netflix investors — they talk to him, pick his brain, listen to him dissect Netflix’s income statement. He has a lot of sources in the entertainment industry and can pass on scuttlebutt about, say, how much it cost Netflix to outbid Amazon Prime for a show.

“There is a hedge fund that is massively long on Netflix,” Pachter said, “and they talk to me all the time. They say, ‘We think you’re wrong, but thanks for the input.’” And even though he is on the wrong side of the argument from their point of view, they still reward Wedbush with commissions for his analysis. They value what he has to say.

I remember a long time ago, when Amazon was the Netflix of its day — a so-called battleground stock that was impossible to value by traditional measures. At the height of the Internet bubble, with Amazon shares at $240, an obscure analyst named Henry Blodget put a $400 price target on the stock. When Amazon hit $400 13 days later, Blodget was suddenly the most famous analyst on Wall Street.

There was another analyst following Amazon: Jonathan Cohen of Merrill Lynch. Like Pachter, he was focused more on Amazon’s numbers than on its growth, and back then its numbers were scary. He had a price target on Amazon, too: $50 a share. Merrill’s army of brokers were not at all happy with Cohen’s bearish stance on Amazon, and they let their superiors know it. Not long after, Cohen left Merrill and was replaced by … Blodget.

When Blodget inaugurated coverage of Amazon after arriving at Merrill Lynch, he wrote, “Amazon.com has blown away expectations since its IPO. It seems reasonable to assume it might continue to do so.” I remembering asking Blodget about that line not long after he wrote it. He shrugged. “It’s something you have to take on faith,” he said.

In fact, although people have forgotten it, Cohen turned out to be right about Amazon. By 2001, the stock had lost two-thirds of its value; it didn’t really take off again until the end of the decade. As for Blodget and Merrill, well, it didn’t work out so well for them, after then-New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer revealed that Blodget had been talking trash about companies he had “buy” recommendations on. Banned from the securities industry, Blodget is now the chief executive of … Business Insider.

I don’t know whether Pachter is going to turn out to be right about Netflix. My own view has been nervously bullish. I agree with him that the debt and negative cash flow are terrifying to contemplate, but I also think that Hastings and Sarandos are unusually smart executives. My working assumption is that they know what they’re doing.

The key thing is this: Just as investors needed Jonathan Cohen’s analysis of Amazon 20 years ago, they now need Michael Pachter’s analysis of Netflix. It takes bears as well as bulls to make a market. And it takes bears as well as bulls to make sense of companies as confounding as Netflix.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stacey Shick at sshick@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Joe Nocera is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He has written business columns for Esquire, GQ and the New York Times, and is the former editorial director of Fortune. He is co-author of “Indentured: The Inside Story of the Rebellion Against the NCAA.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.