Negative Yields Could Be the Death of Bond Markets

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Negative yields have never truly made sense.

And yet, if you work in finance or even just read about markets in general, it’s starting to feel as if the once-absurd (or, at least, strictly academic) is starting to be considered, well, normal. Bloomberg Businessweek’s latest cover in Europe and Asia reads: “No Escape From Low Rates: A Decade of Cheap Money Is Warping the World.” It follows the European Central Bank’s decision last week to keep its key interest rate below zero, and it hinted at cutting the rate even further in the near future.

Someday soon, it might be America’s issue, too. Bob Michele at JPMorgan Asset Management is just one of a growing number of investors who say it’s just a matter of time before benchmark U.S. Treasury yields also reach zero. Researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco wrote that negative rates would have hastened the economic recovery, indicating the type of new tools the central bank may use to combat the next recession.

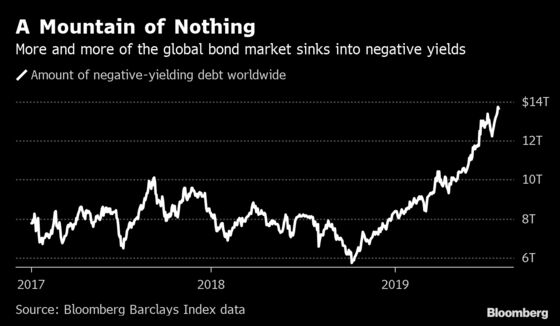

On top of negative rates being a cover story, consider how casually investors toss around the number “$13 trillion,” roughly the amount of debt with sub-zero yields worldwide. Or that negative yields have reached European junk bonds and emerging markets, where the return of principal is far from guaranteed. Or that it’s par for the course that the Bank of Japan controls interest rates by buying up large swaths of exchange-traded funds. Many analysts just write it off as “Japanification” and move on.

A common way to describe this central-bank induced phenomenon is by saying that investors are “paying for the privilege of owning bonds.” I’d call it something else: Setting the stage for the death of the bond market as we know it.

In some ways, the implications of negative yields haven’t sunk in because many investors bought the debt when it offered a positive rate, meaning they’ve seen steady price appreciation and coupon payments at regular intervals. A better test will be whether Germany can continue to issue 10-year bunds that pay no interest at a price above face value, and whether others can do the same.

This is how the bond market dies. Can you even call that sort of thing a bond? It offers no fixed-income payments and guarantees a loss if held to maturity. My hunch is that if this continues unabated, central banks will be one of the few (if not only) consistent buyers of those securities, as they already are in certain corners of the world. After all, they have the ultimate power of effectively printing money to buy assets and don’t particularly care what price they pay. The same can’t be said for pension funds, as I noted in a piece for Businessweek.

With the Fed set to lower its benchmark lending rate this week for the first time in a decade and other central banks running out of options, there has never been a more critical time to assess how to navigate a world with both massively indebted borrowers and return-starved investors. For one, the current state of play allows for the proliferation of zombie companies and zombie investors. Fed Chair Jerome Powell has said his overarching goal is to sustain the expansion, effectively pledging to stick to the status quo of lower-for-longer yields and higher-for-longer risk assets. The question is whether he and other officials can engineer such a soft landing.

Understanding this crossroads is a pressing matter. None other than Ray Dalio, the billionaire hedge fund manager who founded Bridgewater Associates, says a paradigm shift is coming soon in markets, due in large part to massive post-crisis monetary easing and the explosion of debt. He says interest rates have a lower bound “slightly below 0%” and that central banks will keep them pinned there because it’s the path of least resistance.

He wrote the following in an essay on LinkedIn:

“Bonds are a claim on money and governments are likely to continue printing money to pay their debts with devalued money. That’s the easiest and least controversial way to reduce the debt burdens and without raising taxes. My guess is that bonds will provide bad real and nominal returns for those who hold them, but not lead to significant price declines and higher interest rates because I think that it is most likely that central banks will buy more of them to hold interest rates down and keep prices up. In other words, I suspect that the new paradigm will be characterized by large debt monetizations that will be most similar to those that occurred in the 1940s war years.”

Favoring big borrowers over individual savers also has political consequences. CNBC’s Rick Santelli, who is sometimes credited with sparking the Tea Party movement with his rant about the government promoting bad behavior, said earlier this month that he thinks “Americans would hate negative rates” and “at some point, somebody has to rein in the Ph.D’s.”

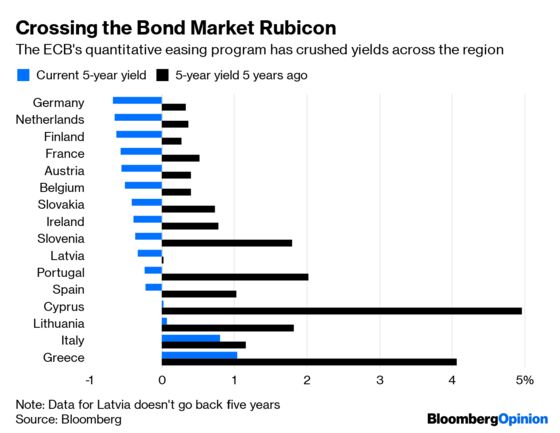

It’s not clear who would do that, though. Politicians love low interest rates, though few besides President Donald Trump say so explicitly. Greek leaders certainly aren’t complaining about being able to borrow for 10 years at less than 2%, nor are Belgium, France and Slovakia, which can issue 10-year debt for nothing even with less-than-pristine credit ratings. Bond traders aren’t staging any sort of buyers’ strike, having learned the hard way the futility of fighting central banks. And traditional 60-40 investors are more or less content with below-zero yields as long as the stock market keeps reaching new highs.

This is a fragile equilibrium. As Dalio wrote in his essay, “There are always big unsustainable forces that drive the paradigm. They go on long enough for people to believe that they will never end even though they obviously must end.”

It stands to reason that negative yields, which are now considered normal, are one such unsustainable force. But if not, and they stay with us for many years to come, it will be because central banks managed to kill off what we all have come to know as the bond market.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.