Negative Rates Are Coming for Your Savings

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- First they came for central banks, then they came for government bonds, then they came for rich depositors. Then they came for me.

Negative interest rates are coming for us all, in one form or another, as central banks redouble their efforts to avert a global economic slowdown that threatens to unleash deflation. So how can we defend ourselves from the coming assault on our bank balances?

Investors seem resigned to the new no-yield orthodoxy in fixed income. Norges Bank Investment Management, the world’s biggest sovereign wealth fund, revealed on Wednesday that it has reversed its longstanding bet that bond yields will climb.

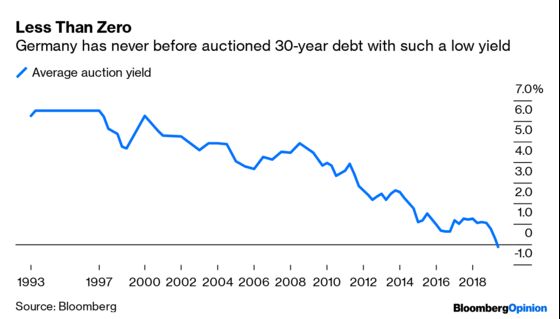

And the government debt market passed yet another milestone this week, with Germany’s auction of the world’s first long-dated bond paying zero interest. Priced to yield -0.11%, buyers are guaranteed – guaranteed – to lose money if they hold the securities to maturity, after paying an average price of 103.61% of face value for notes that will repay at 100% in 30 years.

Of course, you are probably already exposed to negative rates if you have any money invested in an international fixed-income fund. Someone, after all, owns the $16.5 trillion of debt that yields less than zero. With pension funds effectively forced to buy, any money you put away every month to build your retirement nest egg is helping to fuel the bonfire of yields.

But the most direct threat that negative interest rates pose is to our bank accounts. In Switzerland and Denmark, the very wealthy are already being sanctioned. Jyske Bank A/S this week said it will charge Danish depositors with 7.5 million kroner ($1.1 million) or more in their accounts; earlier this month, UBS Group AG halved the level at which its annual 0.6% fee kicks in to 500,000 euros ($560,000).

How long before even lower balances are subject to monetary assault? This threatens to be a key political controversy in coming months.

The prospect of the European Central Bank driving its benchmark rate even lower than its current -0.4% level when it next meets on Sept. 12 prompted Bavarian Prime Minister Markus Soeder to call for a ban on German banks passing the cost on to savers.

Negative rates send “a completely wrong signal and lead to a running down of savings,” Soeder told Bild newspaper this week. He wants legal protection for deposits of up to 100,000 euros.

That tallies with an argument made by Miles Kimball, an economics professor at the University of Colorado. In recent weeks, he has engaged with critics of a paper he published in April with International Monetary Fund economist Ruchir Agarwal that carries the somewhat incendiary title “Enabling Deep Negative Rates to Fight Recessions: A Guide.”

On his blog, Kimball suggests that central banks should incentivize commercial banks to guarantee non-negative rates for smaller checking and savings accounts. “It is precisely zero rates for the ‘wealthy’ and for corporations that need to be disallowed,” he wrote. “There should not be negative rates for people of modest means.”

There’s another way for consumers to prevent their savings being depleted by negative rates, however – by switching to cold, hard cash, tucked under the mattress or buried in the garden. And there’s evidence that people have been stocking up on actual currency.

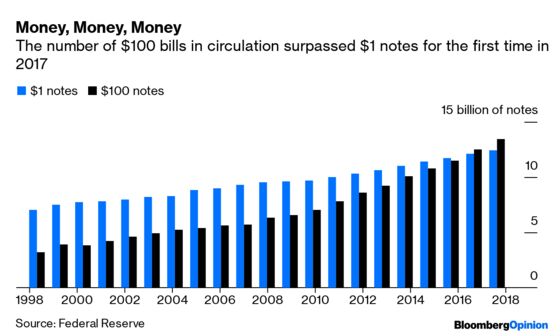

In the past couple of years, the number of $100 bills in circulation has exceeded $1 bills. Moreover, almost 80% of those large-denomination notes are held outside of the U.S., according to the Federal Bank of Chicago, which said in a report last year that rising demand for paper currency in recent years coincides with interest rates falling to zero or below.

A report published in June by the IMF noted that the average American keeps only $60 of cash in hand, so the rise in $100 bills in circulation looks to be driven almost entirely by foreign demand.

“Underground demand for paper currency has been surely rising in part because interest rates and inflation are exceptionally low,” the IMF report cited Ken Rogoff, its former chief economist and now Harvard University economics professor, as saying.

Central banks might find other ways to ensure you bear the burden of their negative rate policies which, after all, are designed to persuade you to spend rather than save. Morgan Stanley Vice Chairman Reza Moghadam, who used to head the IMF’s European department, wrote in the Financial Times last month that central banks could impose a transaction fee on currency withdrawals. “By varying the fee at its cash window, the ECB can operate the system at any negative rate it chooses,” he wrote.

Extricating your savings from the virtual world of the digital banking system and converting them into small pieces of paper isn’t without risk. You could get burgled. Your house could burn down. You could forget where you stashed your cash. So the 25% rise in the price of gold in the past year is probably at least partly driven by concern about negative interest rates. But if you can’t afford the physical storage costs of precious metals and you’re feeling particularly brave, there will always be Bitcoin.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering asset management. He previously was the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is also the author of "Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable."

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.