Markets Need to Keep an Eye on the Lucky Country

Australia has become known as “The Lucky Country” for having avoided a technical recession since 1991.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Australia has become known as “The Lucky Country” for having avoided a technical recession since 1991. It even managed to keep growing while the rest of the world suffered through the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression a decade ago. But now its luck may be running out, and the implications are potentially global.

The Australia dollar is usually one of the major beneficiaries of a global “risk on” rally in markets like the one this year given its close economic ties to China. But instead of appreciating, the so-called Aussie has depreciated 3.50 percent against a basket of developed-market peers over the past year, including a big 1.17 percent plunge on Wednesday. The latest decline came as Reserve Bank of Australia Governor Philip Lowe shifted to a neutral policy outlook as he acknowledged increased economic risks at home and abroad. Indeed, the nation’s economic data has been consistently falling below analysts’ forecasts since the beginning of December as measured by the Citi Economic Surprise Indexes amid a weakening housing market and high consumer debt loads. But the truly important thing is that many international investors view Australia as a proxy for China, and the latest weakness in the economy and the Aussie belie the good feelings that have gripped global risk assets this year. It’s not only currency traders who are worried. Bond traders flocked to the safety of Australian government debt, pushing 10-year yields below 2.20 percent, which is not too far from the record low of 1.82 percent in August 2016.

Of course, a resolution to the trade war between the U.S. and China would go a long way toward easing investors’ concerns, but that’s far from assured. And while Australia’s economy is relatively small at about $1.3 trillion, so are canaries that are sent into those big coal mines.

ITALY SMACKS OF DESPERATION

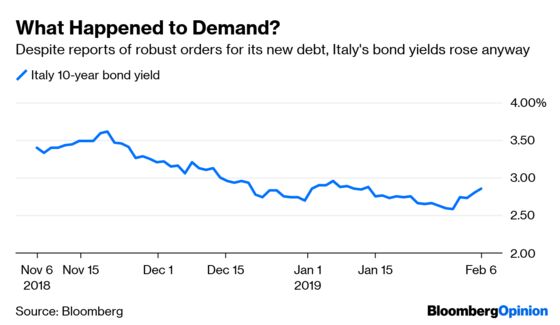

Italy sold 8 billion euros ($9.1 billion) of 20-year bonds on Wednesday, and by all indications the fiscally challenged nation had no trouble attracting demand. Investors placed orders for 41 billion euros of bonds, according to Bloomberg News, citing a person familiar with the matter who asked not to be identified because they’re not authorized to speak about the deal. There’s usually no way of confirming such assertions of robust demand, but one way to tell is to look at how existing bonds reacted. In theory, they should soar as those who lost out on the bidding clamored for what has already been issued. In Italy’s case, its 10-year bonds fell, pushing yields to their highest level since mid-January. “We were a little bit concerned about the timing of this issuance because it was a complete surprise to everyone, and so it does (smack) a little bit of desperation,” Mark Nash, head of global bonds at Merian Global Investors, told Bloomberg Television’s Guy Johnson. What was also odd about the reports of demand is that the sale came on the same day that the International Monetary Fund said Italy’s government was falling short on needed reforms, with annual economic growth projected to stay below 1 percent through 2023. “The authorities’ strategy falls short of comprehensive reforms needed to address the long-standing structural impediments to sustained growth and, therefore, risks leaving the economy vulnerable,” the IMF said in a report.

CUE THE COMPLACENCY CONCERNS

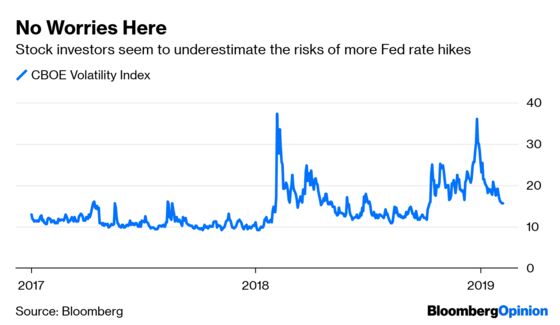

Despite all the challenges facing the global economy and markets — the U.S.-China trade talks, the potential for another U.S. government shutdown, the looming Brexit deadline and the rapidly deteriorating euro zone economy — the widely watched CBOE Volatility Index, or VIX, has fallen to its lowest level since early October. One big reason is that investors overwhelmingly believe the Federal Reserve is done raising interest rates and may even stop shrinking its balance sheet assets. Such speculation outweighs the angst over just about anything else. But what investors seem to be discounting is that the more volatility declines and talk of complacency heats up, the more inclined the Fed might be to raise interest rates, maybe not this quarter or the next, but possibly in the second half of the year. The Fed would almost certainly continue to shrink its balance sheet, withdrawing some $50 billion of liquidity from markets each month. To Bank of America’s strategists, the current environment is much like late 2015 and early 2016, when recession fears were overblown because of temporary signs of weakness in the economy, namely in manufacturing. What investors keep forgetting is that manufacturing makes up only 17 percent of the U.S. economy, and the rest seems in decent shape.

BRAZIL STOCK BUBBLE POPPING?

It hasn’t received a lot of attention outside of diehard Brazil-watchers, but the nation’s stock market had been on an absolute tear — until Wednesday. Brazil’s benchmark Ibovespa index of equities had surged 41 percent between mid-June and Monday before wobbling on Tuesday and then plunging as much as 3.44 percent on Wednesday in its biggest decline since May. Much of the tumble was tied to the escalating troubles at Vale SA, which late on Tuesday declared force majeure on some of its iron ore contracts — something the company said it wasn’t going to do after a deadly dam break in January. Then, a Brazilian state regulator revoked its license to operate a dam key to production at one of its largest mines. As this column noted recently, this situation is a test of new President Jair Bolsonaro, a populist who brought with him big plans for reform that propelled the stock market higher. The question now is whether he will be able to push through his various market-friendly economic proposals, such as easing environmental restrictions and boosting mining production through reforms. The other thing to note is that Brazil is a bellwether emerging market, being the “B” in the BRIC acronym that also includes Russia, India and China. So, any weakness in Brazilian equities has the high potential to turn off emerging-market investors globally. Indeed, the MSCI Emerging Markets Index of equities fell on Thursday.

COPPER UPSETS BEARISH NARRATIVE

With evidence of a global economic slowdown mounting, it’s not hard to build a bearish case against riskier financial assets. That is if it weren’t for copper. The metal, which has a reputation for being a great leading indicator for the global economy given its wide use, has been soaring. On Wednesday, prices rose to their highest since the start of December. Strategists chalked up the recent gains partly to optimism that the U.S.-China trade talks will wrap up amicably. Sentiment “is positive and that’s helping the outlook for copper,” George Gero, a managing director at RBC Wealth Management, told Bloomberg News. But there’s also some fundamentals at play. Orders to withdraw copper from the LME rose 29 percent to 56,725 tons, the highest since November and a sign of rising demand, according to Bloomberg News’s Susanne Barton and Mark Burton. To be sure, at about $6,280 a ton, copper is still down some 14 percent from last year’s high of $7,332 in June. That suggests the recent rebound may have more to do with global recovery in risk assets than anything having to do with a positive outlook on the global economy.

TEA LEAVES

The Bank of England wraps up its Monetary Policy Committee meeting on Thursday, and it’s highly probable that the central bank will continue the trend seen among its peers in recent weeks and express a cautious outlook on the economy. That’s especially true for the U.K., where the inability of lawmakers to agree on a plan to exit the European Union has weighed on the economy and markets. “Brexit-related uncertainties have increased since the last MPC meeting pre-Christmas further limiting the committee’s room” to maneuver, the strategists at RBC Capital Markets wrote in a research report. In fact, U.K. economic growth is set to be sluggish for the next few years even if a Brexit deal is secured, according to the National Institute of Economic and Social Research. In a report, the think tank lowered its estimate for growth this year to 1.5 percent from 1.9 percent and said output would pick up only slightly to 1.7 percent in 2020 and 2021, according to Bloomberg News’s Jill Ward.

DON’T MISS

Don’t Blame the Stock Market for Corporate Myopia: Peter Orszag

Vanguard Defends the Value of Active Bond Funds: Brian Chappatta

Italy Is Playing With Fire in the Bond Markets: Marcus Ashworth

Brexit Delivers a $400 Trillion Market Truce: Lionel Laurent

Even the Right American Is Wrong for World Bank: Mihir Sharma

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.