Macedonia Needs More Patience On the Road to Europe

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Macedonia’s referendum on a proposed name change, which could have opened the Balkan nation’s path to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the European Union, has failed because of a low turnout. The math behind the failure shows why it’s hard to be an optimist about the Western Balkans, Europe’s current frontier.

Sunday’s referendum followed a deal reached by Macedonian Prime Minister Zoran Zaev and his Greek counterpart Alexis Tsipras in June. Tsipras agreed to drop Greece’s opposition to Macedonia’s NATO and EU membership if it renamed itself North Macedonia, to distinguish itself from Greece’s northern region, and dropped the previous, nationalist government’s shaky claims to a connection with the warrior kings of ancient Macedon, especially to Alexander the Great.

The quarrel over identity had lasted for more than a quarter of a century, causing Macedonia, part of the former Yugoslavia, no end of economic and diplomatic trouble. A resolution seemed in sight when the EU’s announced earlier this year that it would accept more Western Balkan nations as members some time in the next decade. Since membership would require those nations to first work out their squabbles, it looked like peace might be finally possible for the war-scarred region still torn apart by stubborn nationalisms. Serbia and Kosovo, too, appeared to be moving toward a settlement of their disputes.

The result of the Macedonia referendum is a sobering reminder that there are no short-cut solutions.

Only 661,393 people, or 36.87 percent of the registered voters turned out on Sunday to answer the question “Are you for EU and NATO membership by accepting the Agreement between the Republic of Macedonia and the Republic of Greece?” Though 91.5 percent of them (or 33.7 percent of registered voters) voted “Yes,” Macedonia’s constitution requires a turnout higher than 50 percent for a referendum to be valid. The plebiscite’s result doesn’t make it easier for Zaev to get the name change through parliament; his party doesn’t have a majority, and a two-thirds vote is required to amend the constitution.

At first sight, it might appear that the disinformation-rich campaign to boycott the referendum, which Macedonian nationalists ran in place of a “No” campaign – succeeded. Russia, which is seeking to delay Macedonia’s NATO membership, backed the nationalists – and we will undoubtedly hear a great deal in the coming weeks about how it had managed to thwart Zaev. In reality, however, the prime minister did a little better on Sunday than he did in the December, 2016 general election.

Back then, the turnout was 67 percent of Macedonia’s 1.8 million registered voters, likely the maximum possible, because up to a third of registered voters live and work abroad, and the country can’t afford to organize absentee voting on any serious scale. Of the 67 percent, 39.3 percent voted for VMRO-DPNE, the nationalist, authoritarian party than had held power for the previous 10 years. (It got more votes than Zaev’s center-left bloc but couldn’t form the government because the biggest ethnic Albanian party switched allegiance to Zaev). Most of the VMRO-DPNE voters would have said “No” to the name change, and it is safe to assume many of them simply chose not to show up for Sunday’s referendum.

That 33.7 percent of registered voters endorsed Zaev’s preferred outcome in the referendum represents an improvement from the 27 percent who didn’t back VMRO-DPNE in the general election. In absolute terms, the prime minister has increased support for his version of Macedonia’s Euro-Atlantic path. But it is not nearly enough.

Zaev’s bid for a quick solution to the dispute with Greece was opportunistic and foolhardy, and it’s not surprising that it failed, despite Macedonians’ overwhelming support for membership in Western institutions. Too many of them have fled the economic hardship and the high unemployment; too many of those who remain don’t feel any urgency about NATO membership — which, unlike EU accession, can come almost immediately after the name change — that would justify a compromise with Greece. And indeed, there’s something to be said for attrition: Greece started out with a harsh economic blockade of newly independent Macedonia, and now is willing to accept relatively small changes to its constitution to settle the long-standing conflict.

Zaev tried to put a good spin on the referendum result, saying all political forces had to respect the will of the people rather than expect a different deal with Greece. But since he is unlikely to get the parliamentary support he needs, another early election is on the cards. Zaev would be favored to win, but he may not get much closer to a two-thirds majority.

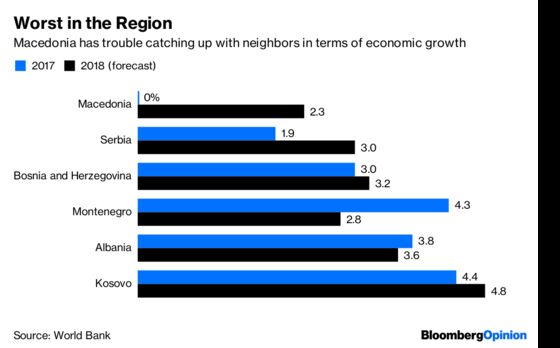

The euro-optimists must now recognize that there is no quick fix. To get the popular support needed for a compromise with Greece, they need to show they can govern the country better than the nationalists did during their decade in power. Last year, Macedonia showed zero economic growth, compared with 2.4 percent for the Western Balkans as a whole; the World Bank forecasts only 2.3 percent growth for this year, less than for any other country in the region.

That is hardly reason for Macedonians working abroad to return home, where unemployment is above 20 percent; it would take a boom like Poland’s, which has resulted in a labor shortage. EU membership, of course, would likely stimulate growth – but Macedonia isn’t even an official accession candidate yet, so that’s going to take time in any case.

As in the Serbia-Kosovo instance, where the sides are actively looking for a compromise but are still far apart, no magic wand will remove long-standing obstacles to peaceful progress. The hopes that have arisen for the region this year aren’t dead, but it will take more than the prospect of EU and NATO membership to produce specific solutions to long-standing problems. Patient political maneuvering, better day-to-day economic management and cautious diplomacy are still the Western Balkans best chance.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Bobby Ghosh at aghosh73@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European politics and business. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.