Merit-Based Immigrants Aren’t the Most Successful Citizens

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Politicians often say they prefer highly skilled immigrants over low-skilled ones. But data show that attracting people with foreign degrees is not necessarily the most efficient policy.

In his State of the Union address speech in January, President Donald Trump said it was “time to begin moving toward a merit-based immigration system. One that admits people who are skilled. Who want to work. Who will contribute to our society.”

In the U.K., where popular dissatisfaction with immigration policies helped trigger Brexit, the focus is on bringing in more skilled immigrants. And in many continental European countries, anti-immigration parties routinely draw a contrast between “merit-based” or “skilled” immigration and recent asylum seekers, often described as dishonest economic immigrants unable to contribute to society.

A fresh report on migrant skills by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development provides often surprising data from developed countries to test that rhetoric. The OECD obtained the numbers not just by analyzing information about migrants’ formal qualifications but also by using a test to determine actual literacy, numeracy and problem-solving skills (I tried answering the test questions in different languages; they aren’t daunting to a college-educated person, but there’s a clear handicap for non-native speakers).

Immigrants, according to the OECD data, are generally less educated than those born in the receiving country. In Germany, 30 percent of immigrants and 15 percent of natives have less than a high school education; in France, it’s 45 percent vs. 25 percent. But in countries with “merit-based” systems, such as Australia, New Zealand and Canada, the picture is reversed: In Canada, for example, 58 percent of migrants and just 42 percent of natives are highly educated. Not surprisingly, such policies also mean that a larger share of locals than of immigrants work in low-skilled jobs.

Countries with selective immigration policies also register the smallest gaps in literacy and numeracy scores between immigrants and natives. In Sweden, for example, the difference is greater because there are a large number of humanitarian immigrants. The gaps are largely explained by the language barrier. The later a person arrives in a country where he or she needs to learn, or start using, a new language, the wider the skills gap. “Linguistic distance” is also important; it’s much easier for a Dutch person to catch up with the natives of an English-speaking country, or for a Croat with Slovenians, than for a Syrian Arabic speaker to close the skills gap with Swedes.

This doesn’t mean, however, that countries with merit-based immigration systems, which are relatively reluctant to open their doors to people who simply need help, are profiting more from their immigration policies than countries at the other end of the spectrum. The skill gaps between natives and immigrants still exist at every education level, and they are much more important for a worker’s competitiveness in highly skilled jobs than in menial ones.

That probably explains why a different set of OECD data -- the 2018 International Migration Outlook -- shows that in all developed countries except Switzerland, college-educated immigrants practice low-skilled occupations more frequently than locals. According to the OECD, a third of college-educated immigrants are overqualified for their jobs, a rate that is 12 percentage points higher than for natives.

In Canada, according to official statistics, the unemployment rate among immigrants with university degrees was 6.1 percent last year, compared with 2.9 percent for native-born Canadians with the same education level. At the same time, immigrants who are high school graduates were as likely to be unemployed as native Canadians with similar credentials.

The “brain waste” problem -- doctors and architects driving taxis or drawing unemployment benefits -- is, arguably, not a bad one for a country to have. OECD data for Canada show, however, that immigrants educated in the host country enjoy much better labor-market outcomes than foreign-educated ones. That’s clear evidence that importing “ready-made” professionals through some kind of point-based system isn’t optimal and a country is better off bringing in bright young people and educating them locally.

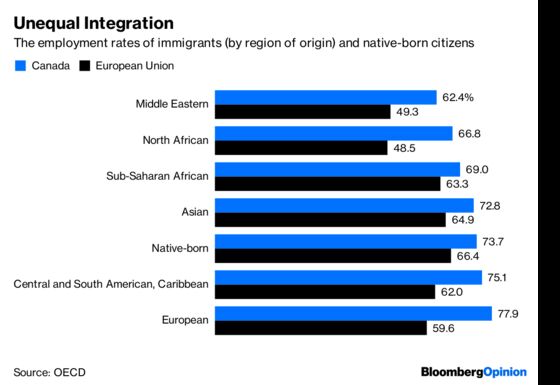

Besides, merit-based immigration systems don’t really help to solve the problem of Middle Eastern and North African immigrants, who, in every destination country, tend to be out of work more often than migrants from other regions. Cultural differences, linguistic distance and entrenched biases tend to keep many of them on the fringes of society both in Canada with its points-based immigration and in Europe, where immigration policies have a more humanitarian bent.

Smart immigration policies shouldn’t be based on “merit,” described as some measure of educational attainment or professional qualification. They should be linked to a country’s integration potential, its ability to close skills gaps created by linguistic and cultural barriers, its strength in training competitive workers at all levels of achievement. Sometimes it makes sense for a country to develop training expertise in areas that don’t require college degrees, such as elder care or tourism, and draw in immigrants willing and able to be trained. Other times, when more highly educated people are required, the host country should pay more attention to testing the abilities of the children applying for entry than to checking their parents’ backgrounds.

Unfortunately, political rhetoric, both of the leftist and the far-right variety, is clouding policy makers’ vision when it comes to devising such policies and building up countries’ integration potential. As international migration increases, the sloganeering creates a time bomb.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Max Berley at mberley@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European politics and business. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.