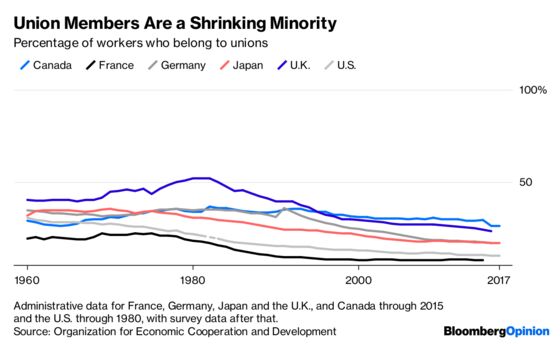

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Unions are on the decline in the U.S., and have been for a long time. Last year, only 6.5 percent of private-sector workers in the U.S. belonged to one. (Among public-sector workers the unionization rate was 34.4 percent and has held relatively steady over time, but the public sector’s share of the workforce has been shrinking since the 1970s.)

You probably already knew that, more or less. But low and declining union membership is not just an American thing (yes, this chart looks a little squished, but I thought I should have the same scale on all of them to make them easier to compare):

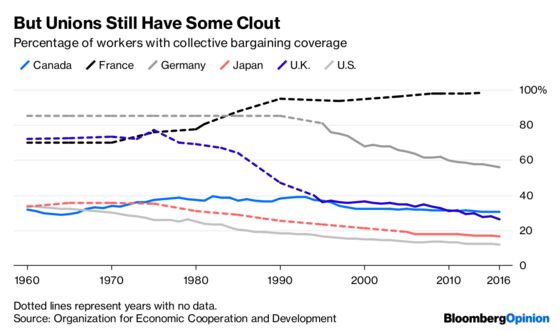

So union membership is even lower in France than in the U.S.! As I learned from the National Review’s Reihan Salam a few years ago when I first discovered this amazing fact, though, that’s kind of misleading. Almost every worker in France is covered by collective bargaining agreements between the country’s unions and employers.

It is French law that has guaranteed this continued strong role for unions even as membership dwindles, and it seems fair to say that the results have been less than optimal. Even with President Emanuel Macron’s recent efforts to increase labor-market flexibility, the French economy remains beset by high labor costs, frequent strikes, a low labor-force participation rate and excruciatingly slow growth.

In Germany, which generally has a better reputation as far as labor-market policies go, unions continue to play a much bigger role than they do in the U.S., but their clout has been on the decline since the 1990s. In the U.K., that decline began in the late 1970s, which happens to be when Margaret Thatcher became prime minister and made breaking the power of unions a top priority. In Canada, the declines in both union membership and collective bargaining representation have been relatively muted, but both did start from a pretty low base.

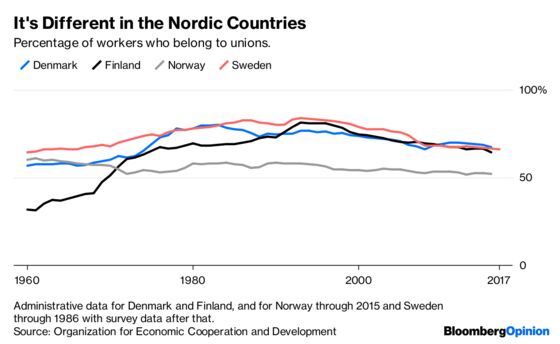

These statistics offer some support both for those who argue that that the union decline has been inevitable (it’s been happening in all the big developed economies, after all) and those who see it as an unfortunate political choice (the timing and the trajectory have differed by country). More backing for the latter argument can be found in the experience of the group of nations with the highest union membership rates in the developed world, the Nordic countries.

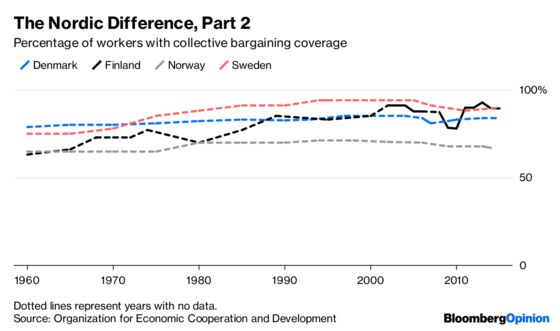

Yes, even Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden have seen declines in unionization since the early 1990s, which is when the region experienced its own local version of the financial crisis and deep recession that beset rest of the developed world in 2008 and 2009. But union membership is still really high! (I should note here that Iceland is also a Nordic country and its unionization rate is even higher, at 90.4 percent in 2016, but it’s so tiny and its historical data so spotty that I left it off the chart.) The percentage of workers covered by collective bargaining agreements is even higher, and holding somewhat steadier.

The thing about unions in the Nordic countries, though, is that they’re different from unions in most other countries. I learned this in Denmark in 2007 when a union steward at Lego A/S, which had just announced plans to move a bunch of factory work to Eastern Europe, gave me an impassioned lecture on the positive economic aspects of outsourcing. Unions in Denmark saw (and presumably still see) preserving the competitiveness of Danish industry as a much higher priority than protecting specific jobs. They arrived at this mindset in part because Denmark is a small country trying to succeed in a big, scary world, but also because access to generous unemployment benefits is what leads many (perhaps most) workers in Denmark to join unions in the first place.

Denmark, Finland and Sweden are what are called “Ghent system” countries, where unions administer the unemployment insurance program with help from government subsidies. Norway used to have a Ghent system but abandoned it in 1938. Belgium, where the actual city of Ghent is located, has a “partial Ghent system.” In recent years, the link between union membership and unemployment insurance has weakened in the remaining Ghent system countries too, with most union-affiliated insurance providers now formally independent, and scholars from those countries have written lots of papers about the pressures the system is under. But from the perspective of many outside observers it still looks pretty great in the way that it combines continued union strength with a flexible, pragmatic approach to serving workers that seems quite compatible with economic competitiveness.

Interestingly, some of the biggest American fans of this approach in recent years have come from the political center-right. The Atlantic’s Jonathan Rauch cited the Ghent system approvingly in making “The Conservative Case for Unions” last year; the Manhattan Institute’s Oren Cass did the same in a City Journal article on “More Perfect Unions”; and in their 2008 book, “Grand New Party: How Republicans Can Win the Working Class and Save the American Dream,” the aforementioned Reihan Salam and New York Times columnist Ross Douthat advocated “new model unions” that would focus more on providing services and training to members than negotiating with their employers.

Some traditional unions in the U.S. are already responsible for providing pensions, which hasn’t been going very well for them lately. The “new model” Freelancers Union, founded in 1995, offers health coverage and other forms of insurance to independent workers, as well as political advocacy. This is an awfully long way from the Nordic system in which unions play a central role not only in providing unemployment insurance but in determining how much money everybody makes. But on Labor Day one can always dream, I guess.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jonathan Landman at jlandman4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.