Japan’s Economy Is Getting a Lot of Things Right

Japan spent years recovering from its asset-bubble bust. @Noahpinion says the country has made up for its lost decade.

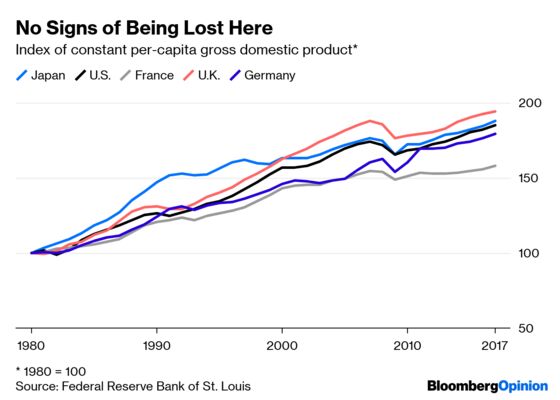

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As Japan’s emperor Akihito prepares to abdicate, what’s known as the Heisei period -- Jan. 8, 1989, through April 30, 2019 -- draws to a close. Those 30 years will forever be associated with the spectacular asset bubble that burst right at the beginning, and the economic lost decade that followed. Heisei was also when Japan’s population peaked and started to decline. But it was a time when Japanese popular culture flourished and gained international renown. And in the 2000s and 2010s, Japan’s growth recovered its footing:

Economically, the period ends on a high note, with record employment rates, and wage growth finally starting to pick up as the retirement of the highly paid baby boom generation stops dragging the numbers down. Meanwhile, throughout its struggles, Japan maintained its ultra-low crime rate, superb infrastructure and transportation, and beautiful, well-kept cities. As Bloomberg’s Brian Bremner writes, Japan has been much more of an example for other nations than is popularly realized.

On May 1, Japan will get a new emperor, and a new era -- the Reiwa period -- will begin. The transition is largely symbolic, as the emperor’s role is ceremonial. But it’s a good opportunity to take stock of where Japan is as a country, and where it needs to go.

Some Western observers have made dark predictions that Japan will turn back toward fascism in the years to come. They have interpreted the characters in the name Reiwa -- which is taken from an eighth-century poem about flowers, and translates roughly as “ordered harmony” or “auspicious calm” -- as a dog-whistle for fascism. This interpretation in turn is based on the notion, popular in some Western journalistic circles, that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is an ultranationalist leader bent on bringing back the autocratic militarism of pre-WWII Japan.

That notion is wrong. Abe does have political ties to some ultranationalists, and he does support the idea of revising Japan’s pacifist postwar constitution. But overall his administration has been a startlingly liberal one. When an ugly anti-Korean hate group emerged during the early years of Abe’s tenure in office, he responded by enacting the first hate-speech law in Japan’s history. Visitors to Japan will notice that the loudspeaker vans that once blared right-wing propaganda through major shopping districts every weekend are now mostly absent from the streets.

Abe’s policies have also been diametrically opposed to those of President Donald Trump and other modern right-wing populists. He has dramatically expanded immigration to the once-insular nation, enacting a guest worker law and establishing a fast track to permanent residency. The number of foreigners working in Japan has soared since Abe took office at the end of 2012:

In Tokyo, 1-in-8 young people coming of age in 2018 was foreign-born. That’s a startling increase in diversity for a historically homogeneous nation. But so far, Japan is embracing the change -- in a recent Pew poll, Japan was the only country surveyed where more respondents said they wanted to increase immigration than wanted to decrease it. Without Abe’s leadership, it’s not at all clear this shift would have happened.

Japan’s society has liberalized in other ways too. A country famous for gender inequality now has a higher female labor force participation rate than the U.S., thanks in part to Abe’s attempts to pressure companies to hire more women and to provide more child-care services. Abe is also taking the lead on free trade, pursuing trade deals with the European Union and keeping the Trans-Pacific Partnership alive. Japan is competing with China to build infrastructure in developing countries.

So despite Abe’s ties to right-wingers, his policies have led to a liberalization and opening of Japan that is unprecedented in the country’s postwar history. This looks nothing like the xenophobic, populist eruptions in the U.S. or the U.K., and certainly nothing like a prelude to fascism.

But in order for Japan to truly prosper during the Reiwa period, much more must be done. There are two big immediate priorities: Changing Japan’s corporate culture, and reforming its justice system.

Japan’s hidebound corporate culture is out of step with the needs of a modern economy. Its seniority-based pay system makes it hard to attract talented young workers, who demand higher starting salaries. A focus on long working hours reduces productivity and makes work-life balance impossible. An atrophied market for midcareer hires stifles the flow of ideas and expertise between companies. And a reluctance to sell family businesses leaves many industries fragmented and overcrowded.

Meanwhile, Japan’s justice system is antiquated and illiberal. As the recent high-profile mistreatment of Nissan executive Carlos Ghosn has demonstrated, the ability of the police to arbitrarily detain and question suspects must be abolished, and forced confessions replaced with due process. The judiciary needs more young, liberal judges who will fight discrimination and uphold the law rather than defend obsolete social norms out of personal preference.

Beyond these pressing challenges, Japan needs to continue its efforts to boost fertility rates by making it easier for women to balance careers and family life, invest in cutting-edge science to maintain its technological edge, and improve relations with neighboring South Korea.

So far, the Reiwa period looks like it’s off to a promising start. The period’s name may mean “harmony,” but signs point to an era of great and needed change.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.