Can a Hedge Fund Quant Remake a City Without Destroying It?

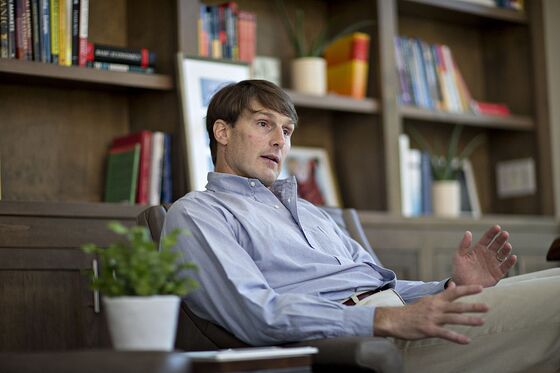

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- I went to Charlottesville, Virginia, a few months ago to talk to a man who had just given his alma mater its largest-ever private gift: $120 million.

The man is Jaffray Woodriff, the school is the University of Virginia, and the gift’s purpose is to establish a school that, he hopes, will advance the frontiers of artificial intelligence, machine learning and other aspects of data science. Woodriff got rich running a quant hedge fund; his Quantitative Investment Management, with $2.8 billion under management, uses black box algorithms to find trading patterns it can take advantage of. Since its founding in 2003, QIM’s cumulative return is 240 percent (though like many quant funds, it was clobbered in 2018, with one of its funds down 42 percent).

“The School of Data Science will establish leadership in a field that already plays a central role in shaping our future,” Woodriff said at the mid-January ceremony unveiling the donation. He added, “The time is right to establish a school which will not only train the finest data scientists in the world but … evaluate and shape policy with respect to the ethical, privacy and regulatory aspects of data science application.”

I have no doubt that Woodriff meant every word he said — and, indeed, if UVA were to develop ways to significantly enhance data privacy, he will have made an important difference. But as I discovered when I met him a few days later, that wasn’t his only agenda. Not even close.

******

With a population of 48,000, Charlottesville is a classic modern university town. It’s got bookstores and music halls. Its restaurants all seem to have embraced the farm-to-table movement. Downtown Charlottesville is dominated by a walking mall lined with interesting shops. It’s livable in another way as well: Most of its houses are affordable on a university professor’s salary, and there are plenty of apartments students can afford.

Woodriff, who’ll turn 50 in April, grew up on a farm in Somerset, Virginia, a speck of a town a half-hour from Charlottesville. Charlottesville was the big city for the young Woodriff, the place he went to go to the movies or have a restaurant meal. When it was time to go to college, there was no question where he was going to go: UVA.

After graduation, Woodriff drove across the country, spending time in cities as varied as Missoula, Montana, and San Francisco. None of them were places he wanted to put down roots. He had a few false starts trying to establish himself as a trader, so he went to work for Societe Generale in New York. When he left the bank and formed a small company with a colleague, he stayed in New York for about a year. But it was always Woodriff’s goal to return to Charlottesville, which he did around 2002. “I’m an introvert and a homebody,” he told me. Charlottesville was the city he loved, and where he felt most comfortable.

His mother, he told me, wasn’t thrilled about his decision to return to Charlottesville, with what she viewed as its limited opportunities. But you can run a hedge fund from anywhere. Woodriff, in fact, isn’t the only hedge fund manager to call Charlottesville home. Ted Weschler, one of Berkshire Hathaway’s two investment managers, lives in Charlottesville. There’s also Guardian Point Capital, Bluestem Assets and a handful of others.

Woodriff told me that he’d always known that “if I were doing well, I would contribute.” He added, “I never really understood making as much money as possible without giving a lot of it away.” The Quantitative Foundation, run by Woodriff and his wife, Merrill, makes lots of donations around town to such worthy causes as the Boys & Girls Club. Still, his first two big gifts were to causes he was personally invested in. He gave UVA $10 million to start a Data Science Institute, a precursor to the new school. And after becoming smitten with squash, he gave the athletic department $12.4 million to build a fancy new squash facility.

Which gets to that other agenda I mentioned earlier. What Woodriff really wants to do with his wealth is transform Charlottesville into a place that will attract more people like, well, him. He hopes that students who attend the School of Data Science will want to stay in Charlottesville after graduation — and that their parents will be thrilled with that choice. “I want people to come here and say, ‘I aspire to this,’ and not interviewing with Google,” he said.

Woodriff was particularly influenced by a series of essays written by Paul Graham, the co-founder of Y Combinator, the startup incubator. “The essays described what you would need for your city to be a startup hub,” Woodriff said. The three main requirements were a research-oriented university, lots of wealthy people, and a vibrant, walkable downtown. “You need to be able to get up from your desk and randomly bump into a wide variety of people who are bright and motivated,” he said. “Palo Alto has that. Bell Labs had that. And I’m trying to facilitate that in Charlottesville.”

Thus, in early 2017, Woodriff purchased the Main Street Arena in downtown Charlottesville, a building that housed, among other things, an ice rink, a concert venue and a café popular with the LGBTQ community. It is being demolished, and will be replaced with a new 160,000-square-foot building with offices for tech startups.

Woodriff’s former partner on the project, Tim Miano, told the Daily Progress of Charlottesville that the city’s startup culture “is on the cusp of becoming a thriving industry” but needed, among other things, more outside talent and downtown office space. Woodriff’s belief is that in supplying the latter the former will take care of itself — as graduates of the School of Data Science set up their new companies in his building, perhaps with his seed capital.

I asked Woodriff whether he was worried that his dream, if it came true, might transform Charlottesville into a city that he might not like as much as the city he lives in now. He waved away my concern. “I don’t think Charlottesville will look all that much different,” he replied. “If we move the percentage of graduates staying in town from two out of 3,000 to 100 out of 3,000, that is an absurdly small percentage.”

I’m not so sure about that. So far the main complaint about Woodriff’s purchase is the removal of the ice rink — though he is helping fund a new one — and that the new building will eliminate some important meeting spaces. “It benefits a small segment of the population, to the detriment of everyone else,” said Michael Payne, a local community activist.

But the larger issue, it seems to me, is that adding 98 entrepreneurs a year to your city, as Woodriff envisions, is not a small thing. Some of those entrepreneurs will go bust, but others will succeed — perhaps beyond anyone’s wildest imagination. I lived in Austin, Texas, in the mid-1980s when it was a comfortable town with a population under 300,000. During that same time, however, a college student named Michael Dell was building computers in his dorm room at the University of Texas. The success of Dell Computers — which now has its headquarters in nearby Round Rock, Texas — utterly changed the character of Austin. Austin’s population today is around 1 million, big tech companies are everywhere, traffic is unbearable, and entire neighborhoods have been razed to make way for high-rise office buildings. People who live in Austin bemoan what’s happened to their city.

Jaffray Woodriff is using his money in ways that he believes will help Charlottesville. But he’s one rich guy, influenced by another rich guy, Paul Graham. He has not involved the government except to get approvals for his new building. Nor has he thought hard about the possibility that one of his startups might turn out to be another Dell Computers. There is a chance that he will change Charlottesville for the better — but there is an equal chance he will change it for the worse.

Which raises the question: For all his money and his good intentions, should one rich guy be able to reshape a city? Or should the city itself have a say in how it might change?

As of October 2018, according to Bloomberg.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stacey Shick at sshick@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Joe Nocera is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He has written business columns for Esquire, GQ and the New York Times, and is the former editorial director of Fortune. He is co-author of “Indentured: The Inside Story of the Rebellion Against the NCAA.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.