(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Spare a thought for Italian banks if you can. Barely recovered from their recent crisis, the country’s lenders find they have stumbled into a new one.

Rome’s populist administration has sent yields on government bonds soaring by passing a budget that busts the EU’s fiscal rules. And since Italian banks still hold hefty amounts of those bonds, investors have taken fright, dumping the lenders’ shares.

The country’s finance industry is better placed to weather a shock than it was a few years ago. But the consequences of prolonged turmoil shouldn’t be underestimated. Banks could restrict credit, which would weigh on the economy. And were one of the weakest lenders to get into serious trouble, the Italian government would face some unhappy choices. That could cause a widespread loss of confidence.

Following Italy’s long recession, its banks have been under severe pressure because of their big holdings of nonperforming loans. Yet there has been an improvement. Bad loans made up 11.4 percent of the total loan book in the second quarter of 2018, down from 15.2 percent in the same period last year, according to Bank of Italy data. Some of the banks in worst shape, such as Veneto Banca and Banca Popolare di Vicenza, have been shut down.

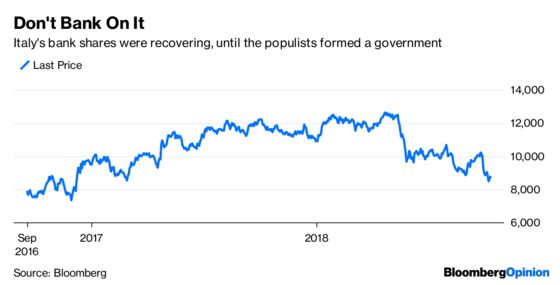

Investors had taken heart from what they’d seen. Between the liquidation of the two Veneto banks in June 2017 and mid-May this year, a sectoral index including Italian banks rose by more than 80 percent. But the formation of a populist coalition in May between the Five Star Movement and the League has halted the rally. The same index has lost more than 30 percent over the past five months.

Italian banks face some very strong headwinds, as the populists have unveiled a long list of lavish promises and started putting some into practice. As lenders have significant exposure to Italian debt, they are highly sensitive to changes in the credibility of the Italian sovereign. An increase of 100 basis points in the sovereign spread between Italy’s bonds and Germany’s bunds reduces the Common Equity Tier 1 capital of Intesa Sanpaolo SpA and UniCredit SpA, the country’s two largest banks, by 35 basis points, according to a note by Citi Research. For UBI Banca SpA and Banco BPM SpA, two mid-sized lenders, this is larger — standing at 56 and 66 basis points.

As the International Monetary Fund warned in its Global Financial Stability Report today, the reemergence of the sovereign risk-banking system nexus in Italy could be destabilizing.

Fortunately, under pressure from the European Central Bank, Italy’s banks have improved their capital position. The average CET1 ratio was 13.8 percent at the end of last year, compared to 7.1 percent in 2008, according to Bank of Italy data included in a study by Intesa. While the largest banks look in better shape, though, some smaller lenders are in a more perilous position.

Indeed, investors shouldn’t take too much comfort from capital strength, even for the biggest firms. For a start, Italian banks are facing an increase in their funding costs because of the spike in bond yields. If prolonged, this could affect their ability to lend. Borrowing costs for families and businesses are still very low, but they started to rise in August. Should they increase further, it might hasten Italy’s incipient economic slowdown. A new recession would undermine the efforts of the banks to cut nonperforming loans, and affect their profitability.

Trouble at any bank would be tough to manage. The new Italian government opposes EU banking rules, which demand that shareholders and bondholders take a financial hit before a government can rescue a bank. Yet were an Italian bank to come under serious pressure, it could be difficult for Rome to avoid state intervention. Investors would be reluctant to provide fresh capital and foreign banks might have better things to do than save an Italian bank. As for fellow Italian lenders, they already chipped in during the last crisis. It would be hard for them to come to the rescue. This could leave the government with no choice but to negotiate a bailout with Brussels and Frankfurt — a very difficult task given Italy’s opposition to the rules.

Italian banks have themselves to blame for keeping so many of their government’s bonds on their balance sheets. But there’s plenty for which they have little responsibility, from the risk of recession to bust-ups with Brussels. Their hope — maybe a forlorn one — is that politicians see sense before it’s too late.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Ferdinando Giugliano writes columns and editorials on European economics for Bloomberg Opinion. He is also an economics columnist for La Repubblica and was a member of the editorial board of the Financial Times.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.