The U.S. Is a Meritocracy. That Doesn’t Mean It’s Fair.

A study says most of those with top 1 percent of incomes are people who work, not the idle rich. But there’s still inequality.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Much of the current debate about inherited wealth in a number of Western countries is informed by the notion that most of today’s top incomes are the product of passive returns on financial capital rather than labor. But in a new National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, four U.S. economists stipulate that much of that income actually comes from the returns on the aptitudes, or human capital, of the working rich; these returns are so great because large human capital is exceedingly rare.

In their important 2018 work, “Distributional National Accounts,” Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman wrote that, “in contrast to earlier decades, the increase in income concentration over the past 15 years derives from a boom in the income from equity and bonds at the top.” This implies that the top incomes of the 20th century – those of top executives, star performers and professional athletes – grew because the richest received bigger pay for work considered unique. Now the elite grows wealthier simply by virtue of owning assets. The authors say the new state of affairs is manifestly unfair, especially since the assets can be passed by inheritance, creating an idle owner class, somewhat like the old aristocracy, that vacuums up much of societies’ cash.

In the new paper, “Capitalists in the Twenty-First Century,” Matthew Smith of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Tax Analysis, Danny Yagan of the University of California at Berkeley, Owen Zidar of Princeton Univesity and Eric Zwick of the University of Chicago take issue with the conclusions of Piketty et al. They argue that about three-quarters of the pass-through business income the biggest U.S. earners receive is, in effect, payment for work or returns from human capital such as expertise, connections and reputation.

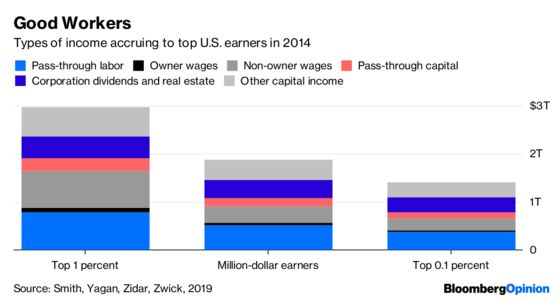

About 84 percent of the top 0.1 percent of earners receive some pass-through income from businesses that aren’t subject to corporate tax. “A typical firm owned by the top 0.1%,” the economists write, “is a regional business with $20 million in sales and 100 employees, such as an auto dealer, beverage distributor, or a large law firm.”

For the top 1 percent, who account for about 40 percent of U.S. wealth, pass-through income typically comes from small professional services firms or medical practices.

The recipients of pass-through income are typically involved in these small and medium-sized businesses; 70 percent of people in the U.S. who earn $1 million work for a living. For tax reasons, they choose to receive compensation as pass-through income rather than wages. Moreover, 75 percent of top earners are self-made, meaning their parents came from the bottom 99 percent.

To figure out how much of that income is the product of the earners’ human capital, Smith, Yagan, Zidar and Zwick compared the income flows from closely held firms in which working-age owners have died or retired to those of companies where the owners remained in place. They found that after death or retirement, profits accruing to owners drop by more than three-quarters. This doesn’t mean the companies are no longer well-managed once the founders are gone: A lot of the profit now goes to professional outside managers.

Studying the effects of owner death and retirement led the researchers to conclude that about 75 percent of pass-through income is the product of labor rather than capital. “An important role for human capital is consistent with the view that the demand for top human capital has outpaced its supply, with the returns to top human capital increasingly taking the form of business income,” they wrote.

In other words, people with a high human capital – outstanding expertise, lucrative networks, a stellar reputation -- are in such great demand that their earning potential has gone through the roof in this century, and high earners have mostly seen fit to record their earnings as business income rather than wages. This is meritocracy at work rather than some kind of aristocracy-formation process.

The findings in the Smith paper, however, aren’t necessarily a moral justification of modern capitalism. As the authors point out, “returns to top owner-managers need not be socially optimal.” Their human capital can include connections within the country’s elite or access to lucrative government contracts. Privilege and corruption aren’t fair or socially useful, but they do boost some people’s earning potential.

Researchers and wealthy individuals often discuss the pitfalls of passing fortunes by inheritance. But even if governments take most of the assets away through taxes or if the top 0.1 percent decide to leave their children nothing but a good education, the kids will still get an unfair start compared with the rest. They’ll be able to draw on their parents’ networks, including their “socially suboptimal” parts, and the fortunes they make in the process will be booked under “returns to human capital.” That’s not particularly meritocratic.

Leveling out this sort of unfair advantage defies simple solutions. Even estimating the share of income that accrues to inherited social capital is no easy task; we know, for example, how much money Donald Trump inherited from his father, but we don’t know how much of Trump’s subsequent income is attributable to his father’s connections. And yet, if Smith and collaborators are right and human capital is king, this kind of inheritance -- sometimes from parents in the 99 percent, too --- could well be an important contributor to income inequality.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Max Berley at mberley@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.