Guess Which Mediterranean Economy Didn’t Crumble

In a first in nine years, global investors snapped up 2.5 billion euros worth of Greece’s 10-year bonds last month.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Greek revival is an architectural style involving columns of marble. It’s also a good description of a ridiculed nation’s prestige among investors, involving columns of numbers measuring unexpected economic durability.

Global investors snapped up 2.5 billion euros worth of Greece’s 10-year bonds last month, the first such offering in nine years. That made the Hellenic Republic's debt the world’s most prized, buoyed by gross domestic product growth that’s outperforming Germany, France and the euro zone.

Greece reached its bailout deal with European creditors in the summer of 2015 after some of the smartest people earlier that year predicted default and exit from the European Monetary Union.

Former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan told the British Broadcasting Corp. then that it was “just a matter of time” before Greece abandoned the shared currency and the euro disintegrated. George Soros, the billionaire chairman of Soros Fund Management, said in an interview with Bloomberg Television a month later that “Greece is going down the drain.” Marcel Fratzcher, the Oxford- and Harvard-educated former head of policy analysis at the European Central Bank and president of the German Institute for Economic Research, went so far as to characterize Greece as a “political and economic catastrophe.” Amid predictions that Greece would abandon the euro and revert to the drachma in a desperate ploy to reassert control over its economic future, Fratzcher declared: “A Grexit is and remains the worst option for Greece. It is becoming more and more likely.”

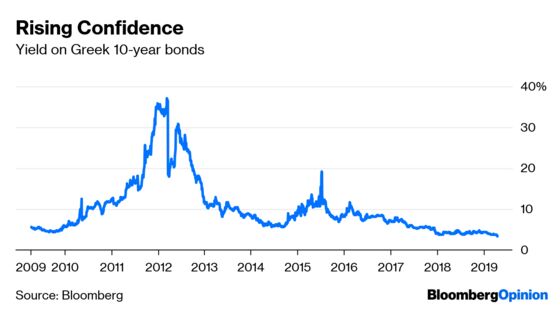

The catalyst for the gloom-mongering was just-elected Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras's seemingly contradictory mandate to end five years of reduced government spending during a depression while securing the final 7.2 billion euros ($8.1 billion) of 240 billion-euro bailout funds from resistant European Union creditors. But public opinion polls in Greece failed to show any preference for returning to drachmas. That's why investors shared little of the rest of the world’s anxiety. While the yield on benchmark Greek bonds briefly touched 19 percent in July 2015, reflecting the country’s economic uncertainty, it remained well below the high of 30 percent in March 2012 and descended during a bull market for developed government debt.

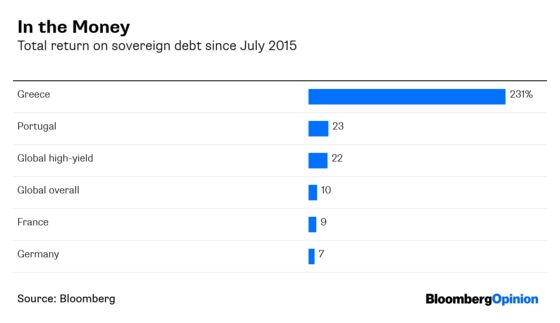

When Greece's newly minted notes of 2029 were priced this March to yield 3.9 percent, they rallied seven consecutive days, confirming the scarcity of the outstanding securities that were yielding 3.3 percent, the lowest borrowing cost for Greece since September 2005, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Nothing in the sovereign bond market since 2015 comes close to matching the performance of Greek debt, which handed investors a 231 percent total return (income plus appreciation). No. 2 Portugal returned 23 percent, while Germany and France gained 7 percent and 9 percent, respectively. The global debt market produced a 9.6-percent total return, the emerging market gained 18 percent and risky global high-yield securities appreciated 22 percent during the past four years, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Greek debt proved to be the signal of EU resilience in the noise of hopelessness amplified by the U.K.’s 2016 vote to leave. Money managers from Belgium, Canada, France and Italy reaped a bonanza, with Newark, N.J.-based Prudential Financial Inc. becoming the largest holder at 7.2 billion euros, or 9.5 percent of the total debt outstanding.

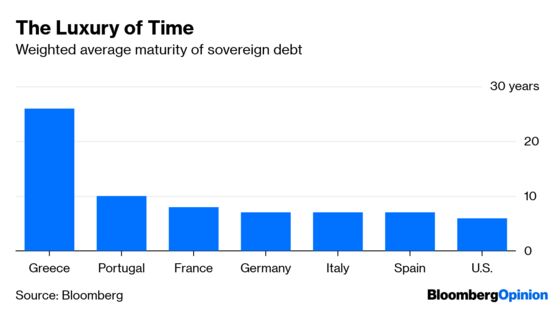

Toronto-based Royal Bank of Canada recently bought 84 million euros ($96 million) worth of Greek securities, according to public filings compiled by Bloomberg. Greece's debt continued to accumulate, with its debt-to-GDP ratio rising to 181.9 percent from 82 percent in 2006, the second-highest among the 25 developed economies. But investors could take comfort in average maturities of more than 25 years, almost four times similar obligations for Spain and Italy and more than double the comparable debt of Portugal.

None of the major European countries is growing as fast as it did at the beginning of the new century. Greece is no exception and suffered its worst contraction in 2012, with unemployment rising to a record 27.7 percent a year later. For investors, that was the most favorable buying opportunity. The GDP rebound since then has overtaken Germany and France, with the 1.9 percent projected pace of Greece’s 2019 expansion putting it at No. 10 among the European GDP leaders, substantially above the expected euro zone average of 1.4 percent, according 21 economists surveyed by Bloomberg.

The jobless rate is poised to decline to 16.5 percent by 2020. The ratio of Greece’s budget deficit to GDP, which rose to a high of 15.1 percent in 2009, turned into a surplus of 0.5 percent in 2016, the first annual favorable outcome since 1995, and widened to 0.8 percent last year. The surplus will prevail for at least three more years, according to 11 economists surveyed by Bloomberg.

The Greek revival isn't only the story of debt. The 60 companies in the Athens Stock Exchange General Index produced a 25 percent total return so far this year, the No. 2 market for shares among the world's 94 major indexes. Among the 569 banks in the world with a minimum market capitalization of $1 billion, Greek banks returned a world-beating 45 percent in 2019.

“Markets have priced in a political change that favors investment in Greece and political stability after the national election,” said Kyriakos Mitsotakis, president of New Democracy, in an interview in his Athens office last week. Mitsotakis served as minister of reforms between 2013 and 2015 and is leading in polls to become Greece's next prime minister this year.

To be sure, the three banks among the 569 with the highest ratio of nonperforming assets to total loans are all Greek.

“Markets are anticipating a collapse of the nonperforming-asset-to-total-loan ratio at the end of the next three-year period as a result of a much better legal environment, the efforts made by banks, the application of systemic solutions and the acceleration of the growth rate of the economy which, if certain conditions prevail, can double its current rate of growth,” said Yannis Stournaras, governor of the Bank of Greece in an interview at the central bank last week. Stournaras was the minister of finance who negotiated the second bailout program between 2012 and 2014.

One measure of the improvement already is evident: The volatility of Greek shares, or the daily fluctuation of values in Greece compared with equity in the rest of the world, is collapsing, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

That means investors are showing the highest confidence in corporate Greece in more than a decade.

--With assistance from Shin Pei and Richard Dunsford-White.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jonathan Landman at jlandman4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Matthew A. Winkler is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is the editor-in-chief emeritus of Bloomberg News.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.