Maybe It’s Time to Stop Blaming Gerrymandering for Everything

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Gerrymandering has over the past few years become something of an all-purpose boogeyman for Democrats frustrated with the way the political winds are blowing. Even after a successful election in which the party won back control of the House of Representatives for the first time in eight years, one can still find people grumbling about it.

And sure, it is possible to find evidence of gerrymandering — the drawing of legislative districts to favor one party over another — in Tuesday’s election results. In North Carolina, where the congressional map concocted by Republican state lawmakers after the 2010 Census was ruled unconstitutional by a federal court in August but allowed to stay in place for this election, Democrats got 48.3 percent of the House vote on Tuesday yet won only three of the state’s 13 House seats.

Nationwide, though, Democrats had 51.5 percent of the House votes counted when last I checked, and they seem likely to win at least 230 of 435 House seats, or 52.9 percent. That popular-vote share is expected to rise by another percentage point or two as more votes are counted, so let’s just say the Democratic popular-vote percentage will be roughly equal to the party’s share of House seats.

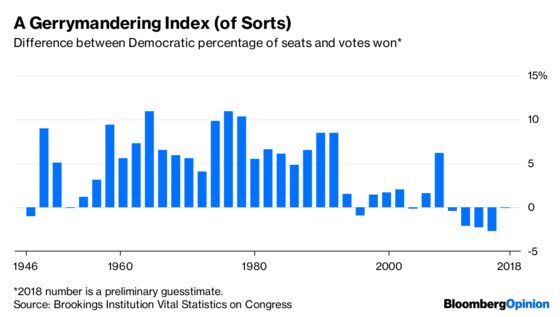

There’s no reason these percentages should be perfectly equal, and it’s not always the fault of gerrymandering when they diverge widely. But comparing the two gives us at least some sense of when gerrymandering might be having a big impact and when it might not, so here are the House vote/seats differentials for the Democrats since 1946, courtesy of the Vital Statistics on Congress database maintained by the Brookings Institution:

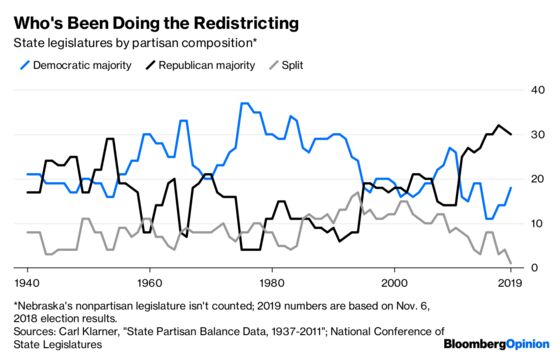

For decades, then, Democrats got a much higher share of House seats than their share of the popular vote. That's partly because in every election from 1954 through 1992, the Democrats got more than 50 percent of the House popular vote, often much more, and a first-past-the-post, single-member-district electoral system like we have in the U.S. can often accentuate the advantage of a majority party. But it can't be entirely coincidental that from the late 1950s through the mid-1990s, Democrats also controlled most state legislatures and were thus responsible for drawing most U.S. House district lines:

This isn’t a perfect measure of who controls the process, as governors play a role too and some states have taken redistricting at least partly out of legislators’ hands (more on that in a moment). Also, it’s not weighted by state population, and Republican control of, say, both houses of the South Dakota Legislature has no effect at all on U.S. House redistricting because South Dakota has only one House seat. Still, it gives a sense of which way the political balance was tilting, and seems to help explain a few interesting phenomena like the Democrats’ continued hold on the House of Representatives during the Republican “revolution” of President Ronald Reagan. It also makes clear that the redistricting following the U.S. Census of 2010 was the Republicans’ first chance to dominate the redistricting process in a really, really long time.

As the first chart hints, they do seem to have taken advantage of this opportunity. The 2012 election was the only one since 1946 in which the party that won the House popular vote (the Democrats got 48.3 percent to the Republicans’ 46.9 percent) didn’t win control of the House, and the Democrats’ seat share trailed their vote share by even more in 2014 and 2016. An Associated Press analysis last year concluded that gerrymandered districts gave the GOP a 22-seat advantage in the 2016 House elections.

Gerrymandering doesn’t always keep working as planned, though. The practice usually involves creating a minority of districts in which the opposing party is likely to win in a landslide, and a majority that your party can expect to win by smaller-but-still-comfortable margins. Shifting demographics and political loyalties can render these assumptions about voting behavior less and less reliable as the years pass after a census, and wave elections can turn those smaller-but-still-comfortable margins into sweeping losses. Both forces were at work this week in Dallas County, Texas: In 2011, reports the Texas Tribune, Republicans in the Texas House of Representatives drew new district lines intended to give them the majority in eight of Dallas County’s 14 state House seats even though the county as a whole was majority Democratic. On Tuesday, Republicans won only two of those 14 seats despite getting about one-third of the overall popular vote (that’s 14 percent versus 33 percent).

This kind of gerrymander-backfire doesn’t seem to have happened in a big way on the national level this week — if it had, one would expect the Democrats to get a much larger share of seats than of the popular vote, as the party did in the Watergate election of 1974 and the GOP did in 2010. But there will be another chance in 2020 and, given how well the Democrats did despite a quite strong economy on Tuesday, a downturn or even slowdown could conceivably put dozens more seats within reach.

Then, after the 2020 Census, we’ll get another round of redistricting! Despite big Democratic gains in state legislative races this week, Republicans remain in the driver’s seat in most states for now, so it’s possible we’ll just start another cycle of Democrats complaining about gerrymandering in 2022.

They will probably have less to complain about, though. There are currently six states in which congressional district lines are drawn not by state legislators but by independent commissions, some politician-appointed and some not, and voters in Colorado and Michigan chose Tuesday to add their states to that list. Several other states constrain lawmakers’ redistricting choices to some extent, with Missouri, Ohio and Utah all taking steps in that direction this year and more states considering changes. That, and there are redistricting lawsuits pending in 13 states.

If I were a Republican politician, I imagine I would see this turn against gerrymandering as more than a tad unfair: The Democrats got to do it for decades, and now that Republicans finally get their chance, everybody wants to make it illegal. Then again, in some of the most aggressively gerrymandered states, such as North Carolina, today’s Republican gerrymanderers are often direct political heirs of the Democratic gerrymanderers of yesteryear. What’s more, almost everybody in the U.S. except for elected officials belonging to parties currently in control of state legislatures really does seem to want to make gerrymandering illegal. Redistricting reforms are extremely popular among voters of all political stripes.

Redistricting reform isn’t magic. Independent commissions still have to make difficult choices with political consequences, and there isn’t complete consensus on which factors (competitiveness, contiguity, representation of different demographic groups, etc.) should weigh heaviest in drawing district lines. But taking those politicians who seek mainly to advance their parties and protect their jobs out of the equation does seem to be a step in the direction of greater public voice and confidence in the political system. That is, it may be a step in the direction of less grumbling.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.