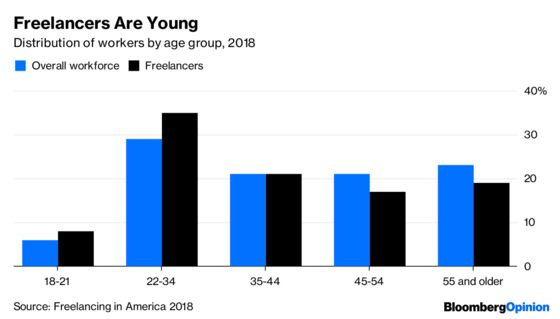

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The gig economy or freelance economy or free-agent nation or whatever you prefer to call it sounds like it’s something for the young folk. That’s certainly the impression one gets from the Freelancing in America 2018 survey released in September by online talent marketplace Upwork Inc. and the Freelancers Union, which broadly defines freelancers to include people who mix occasional gigs with full- or part-time jobs:

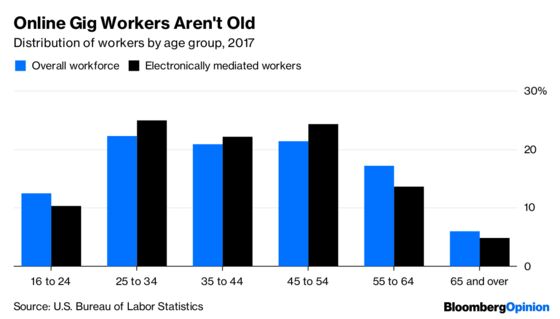

The first-ever Bureau of Labor Statistics survey of “electronically mediated employment,” conducted in May 2017, also found a skew toward youth, albeit a less pronounced one, among those who reported doing “short jobs or tasks that workers find through mobile apps that both connect them with customers and arrange payment for the tasks.”

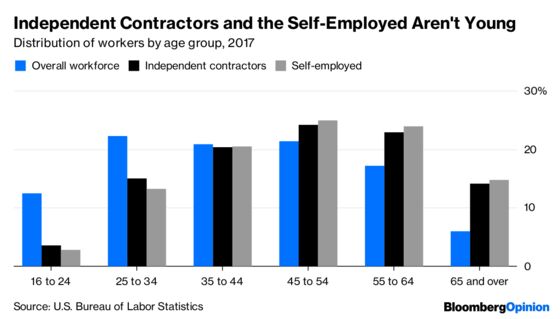

To slice it another way, 41 percent of employed people 65 and older and 23 percent of those 55 through 64 are either self-employed or working as independent contractors. Only 11 percent of those 25 through 34 are. This makes sense, in that older workers are more likely to have the experience and connections to make a go of independent work (and are also probably more likely to get the boot from full-time jobs by employers looking to cut costs). But it also illustrates that, when we talk about the gig economy or freelance economy or free-agent nation or whatever you prefer to call it, we are often grouping very different things together.

My impression is that such talk first took off in a big way in 2015 — an impression that, at least in the case of the phrase “gig economy,” is backed up by Google Trends.

There were surely multiple reasons for this takeoff, among them the desire of a bunch of startups brokering work via smartphone apps to give the impression that they were surfing a huge labor-market wave. But I wouldn’t underestimate the role played by a report that the Government Accountability Office published in May 2015 estimating that 40.4 percent of U.S. workers were in work arrangements that could be classified as “contingent.” This figure, based on 2010 data, was up from 30.6 percent the last time the GAO had made such an estimate, based on 2005 data. It was enough to give one the impression that gig work, broadly defined, was rapidly taking over the U.S. economy.

More than three-quarters of that 40.4 percent was made up of independent contractors, the self-employed and part-time workers. I wrote a couple of columns at the time arguing that the part-timers in particular were skewing the numbers. Part-time work’s share of employment has a strong cyclical component, usually peaking at the end of a recession or early in the subsequent recovery. (Sure enough, it peaked in early 2010 and has been falling since.) Another issue with the GAO’s 2010 number was that it was derived from a different and probably less reliable source than the 2005 one, which came mainly from a Bureau of Labor Statistics survey on contingent and alternative work arrangements that hadn’t been conducted since then because of budget constraints.

The BLS finally did conduct that survey again in 2017, and when it released the results last June they showed that the percentage of U.S. workers in contingent and alternative arrangements had actually declined slightly since 2005 and was only barely above the levels of 1995. Because of the way the BLS defines things, these results included only a minority of part-timers and self-employed workers, the rest of whom the GAO had added in to get its contingent worker totals. While I don’t have access to 2017 data exactly equivalent to what the GAO used for 2005, I’m close to certain that the 2017 contingent worker share of employment would also be slightly lower by the GAO’s reckoning than 2005’s. This makes me feel pretty good about those columns I wrote in 2015! But it also gives the mistaken impression, reflected in a lot of the subsequent media headlines last summer, that nothing much had changed in the labor market since 2005.

What hasn’t changed much are the sizes of the big categories of part-timers, independent contractors and the self-employed. Part-time work’s share of employment rose a lot in the 1970s and 1980s as more and more women entered the workforce, but since 1990 its movements have been, as already noted, mostly cyclical. Its age distribution is bimodal, with such work more prevalent among those under 25 and over 54 than among those in between.

Independent contracting and self-employment are, as indicated above, skewed toward older workers. They are also long-established work arrangements in the U.S., with the former holding more or less steady as a share of employment since it was first measured in the mid-1990s and the latter on a modest downward trend since then and probably since at least the 1940s (“probably” because only the data on unincorporated self-employment goes back that far). If this seems odd given all the recent talk about freelancing’s rise, listen to Lucas Puente, economist at Thumbtack, an online marketplace for home repairs, lawn care and a lot of other not-exactly-newfangled services: “The point I always want to drive home is that a lot of these occupations have always been done in what the BLS calls alternative arrangements.” They aren’t necessarily in growth industries. Employment in construction, a big sector for independent contractors, has been rising in recent years but is, after an epic housing bust, still below the levels of 2005 through 2008. Agriculture, where self-employment is an ages-old tradition, has been shedding jobs in the U.S. for a century. It accounts for just 8 percent of unincorporated self-employment now, down from 27 percent in 1967.

The ranks of part-timers (27.2 million as of October), independent contractors (10.6 million as of May 2017) and the self-employed (15.8 million as of October) dwarf the 1.6 million people, or 1 percent of the workforce, that the BLS estimates did “electronically mediated” work during its survey reference week in May 2017. But that’s still 1.6 million people who presumably weren’t getting work via apps a decade ago. Also, since the data only covers a week, it misses less frequent workers. A JPMorgan Chase & Co. Institute study of customer checking accounts found that 1.6 percent of them had as of March 2018 gotten some income from online platforms in the past month and 4.5 percent had received such income in the past year, although the income amounts were generally small.

Then there are the people counted in Freelancing in America 2018, where almost all the growth since the first survey in 2014 has been among “diversified workers” with multiple income sources from freelance and traditional work (the number classified as independent contractors, meanwhile, has fallen sharply). This year’s report estimated that there 17.6 million such diversified workers. A lot of them do freelance work only occasionally, there’s no pre-2014 data to compare with, and the number is based on a much smaller survey sample than the ones conducted for the BLS. But it does seem to indicate that there are interesting new things going on at the younger end of the gig/freelance economy that we shouldn’t dismiss just because the older, more established parts are declining or treading water.

In short, one should treat claims that freelance or gig or independent work is exploding or becoming the norm with great suspicion. But one should also keep an eye on it.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.