The Fed Isn’t Sending a Signal to Buy Stocks

Set aside intuition and recent experience. The data don’t support the conclusion that lower interest rates bolster equities.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s time for investors to fight the Fed.

A popular Wall Street saw is that the Federal Reserve has a heavy hand in the level of the stock market. The theory is that low interest rates buoy stocks and that high rates sink them, so by controlling interest rates the Fed controls the market indirectly. From that nugget springs the conventional wisdom: Buy stocks when the Fed cuts rates and sell them when it hikes. Or, as the admonition is better known, “Don’t fight the Fed!”

Investors are likely to be reminded of that in the coming months. The 10-year Treasury yield is roughly 0.3 percentage points lower than the yield on three-month T-bills, the largest inversion since early 2007. The central bank lowered the fed funds rate 25 basis points last week and is widely expected to keep cutting to right the yield curve.

It’s tempting to assume that a renewed rate-cutting campaign will bolster stocks. Lower interest rates allow companies and individuals to borrow more cheaply, which in theory should encourage more spending and investment and thereby goose the economy and corporate profits — and stock prices by extension. Lower interest rates also punish bond investors, which should nudge them to seek higher returns in riskier assets such as equities.

Recent experience reinforces that intuition. The central bank dropped the fed funds rate to near zero in response to the 2008 financial crisis, and the rate has remained well below its historical average. Meanwhile, the U.S. has enjoyed the longest economic expansion on record, corporate earnings have ballooned, and the broad U.S. stock market has more than quadrupled in value since the financial crisis. Investors who stayed on the sidelines or sold stocks along the way paid a heavy price.

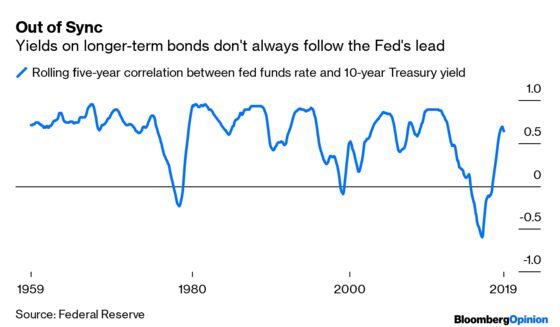

Before investors stuff more U.S. stocks into their portfolios, however, it’s worth asking whether intuition and recent experience jibe with the longer history. The answer is no. Let’s start with the assumption that the Fed has sway over longer-term interest rates. It’s true that since 1954, the longest period for which numbers are available, the fed funds rate and 10-year Treasury yields have been highly correlated (0.91). But that correlation often breaks down for years, and even turns negative, as it did recently from 2012 to 2016 (-0.48). In other words, there’s no guarantee that longer-term rates will take their cue from the Fed. (A correlation of 1 implies that two variables move perfectly in the same direction, whereas a correlation of negative 1 implies that two variables move perfectly in the opposite direction.)

And even when the fed funds rate and longer-term yields move together, it’s not clear which one is leading the dance. These days, it appears more likely that the Fed is chasing the 10-year Treasury yield than the other way around. That’s an important distinction. If the Fed is simply parroting the moves of longer-term bonds, stocks have most likely already digested those moves.

It’s also not clear what impact interest rates have further afield. There’s been no meaningful correlation between yields and nominal annual GDP growth since 1930 (0.11), based on data compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. The same is true when comparing yields with GDP growth over subsequent three-year (0.10), five-year (0.09) and 10-year periods (-0.02).

Similarly, there’s been no correlation between yields and annual earnings growth since 1872 (-0.09), according to data compiled by Yale professor Robert Shiller. Here again, the same is true when looking at earnings growth over longer subsequent periods.

What about lower interest rates sending investors into the stock market in search of higher returns? There’s little support for that, too. There appears to be no correlation between yields and what investors are willing to pay for stocks, either based on 12-month trailing price-to-earnings ratios since 1871 (-0.11) or cyclically adjusted P/E, or CAPE, ratios since 1881 (-0.16). That squares with recent experience in Japan and many European countries where, unlike the U.S., low or even negative interest rates have coexisted with muted stock valuations for years.

So contrary to popular perception, central bankers probably can’t control the stock market or investor behavior, at least not in any reliable or predictable way. Still, investors have undoubtedly chased U.S. stocks in recent years, often citing low interest rates as a motivation. A common refrain is that lower interest rates allow them to pay more for stocks and still expect the same or higher premium over bonds.

Yes, the premium currently priced into markets approximates its long-term average. The earnings yield for U.S. stocks has averaged roughly 6%, based on the inverse of 12-month trailing P/E ratios since 1871 or CAPE ratios since 1881, or an average premium over government bonds of 1.5 percentage points. Today, the earnings yield is 3.3% based on the CAPE, or 1.6 percentage points more than the 10-year Treasury yield of 1.7%. And based on the 12-month trailing P/E ratio, the earnings yield jumps to 5.2%, or a premium of 3.5 percentage points.

But while the premium may be the same — or more generous, depending on one’s preferred measure — the risk is considerably higher. Based on the way earnings yields have moved in the past, investors can expect them to land somewhere between 3% and 23% roughly 95% of the time. With yields already at the lower end of that range, they’re far more likely to move higher than lower, which is almost always the work of lower stock prices rather than higher earnings.

It’s useful to keep all that in mind if the Fed continues to lower rates in the coming months. It won’t mean the stock market is predestined to move higher or that investors ought to pile more risk into their portfolios.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.