Fed Gives Markets What They Want, Not Deserve

An overly dovish tilt leads market commentary. Plus, a descending dollar, African aspirations and more.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The Federal Reserve managed to exceed expectations on Wednesday by scaling back its projected interest-rate increases this year to zero and saying it would stop shrinking its balance sheet assets in September. Before the announcement, the markets were generally expecting the central bank to keep one rate hike on the table and allow its balance sheet to contract through the end of the year – so it’s no surprise that stocks rose from their lows of the day and bonds soared. But the big questions are, why so dovish and at what cost?

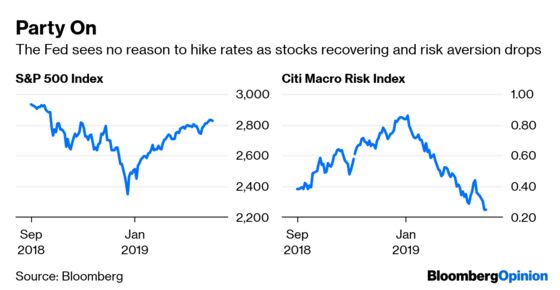

Yes, the central bank lowered its economic-growth projections for this year and next to 2.1 percent, a full percentage point below 2018’s pace, but this year’s rebound in equities and credit markets means that financial conditions are as loose now as any time in the past five years, based on the Bloomberg U.S. Financial Conditions Index. Plus, investors’ aversion to risk is the lowest since early 2018, as measured by a Citigroup Inc. index. The point is, the Fed made clear in January that it was willing to be “patient” in part to keep equities from extending December’s big drop and damaging the broader economy. But with stocks and risk appetites having recovered, that rationale should no longer be in the mix. Policy makers would have lost nothing by forecasting one rate increase later in the year. “The Fed is in a very strange place right now,” Bleakley Financial Group chief investment officer Peter Boockvar wrote in a note to clients. “They backed off from tightening early this year because the market drop scared them into believing markets knew something about the economic outlook. If there was symmetry in their thinking, they should be thinking about tightening again.”

The Fed built up a lot of credibility among investors the last few years by raising rates nine times in a measured manner that didn’t roil markets. Equities gained, credit markets continued to hum, government bond yields remained relatively low and volatility was muted. But now, the Fed is becoming less predictable and markets may end up suffering as a result. Perhaps that’s why stocks only briefly rose after the announcement before closing lower.

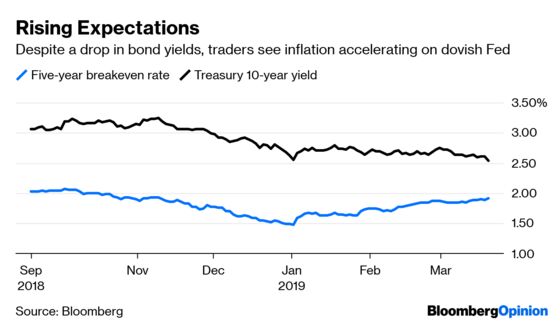

INFLATION EXPECTATIONS INCREASE

Despite the big drop in bond yields, one thing that the Fed managed to do was elevate inflation expectations, which isn’t a bad thing. Breakeven rates on five-year Treasuries — a measure of what bond traders expect the rate of inflation to be over the life of the securities — rose to the highest since mid-November. The rate, which dropped below 1.50 percent in early January, reached as high as 1.91 percent Wednesday. The Fed views inflation expectations as something of a self-fulfilling prophecy in that if markets and consumers expect faster inflation, it will likely happen. A little inflation is also a sign of a healthy economy. The Fed formally adopted its 2 percent inflation goal in 2012, and price gains have mostly come in below that level since then. Policy makers slightly lowered their expectations for inflation relative to their last set of economic projections. After 1.8 percent headline inflation in 2019, they see price gains of 2 percent on both the main and core indexes for the next two years, eliminating the overshoot they had previously projected, according to Bloomberg News’s Jeanna Smialek.

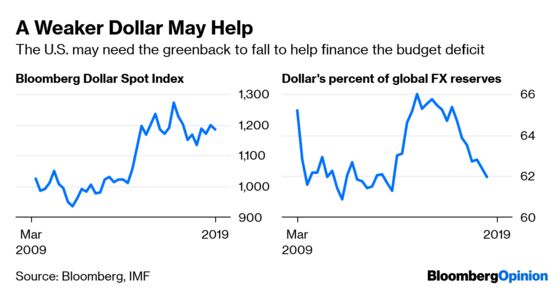

THE DOLLAR DESCENDS

The big loser from the Fed’s decision was the greenback. The Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index dropped to its lowest level since the end of January. President Donald Trump has expressed frustration that the dollar is too strong for the U.S.’s own good, and he’s not necessarily wrong. While Trump sees a weaker dollar as a way to make exporters more competitive, there are other benefits that probably take priority at the moment. The $1 trillion dollar budget deficit facing the U.S. and the related widening in the current-account deficit means the U.S. is becoming even more reliant on attracting foreign capital. As the economists at Citigroup pointed out in a research note Wednesday, this is easily achieved when the economy is strong via higher bond yields and credit spreads; it becomes a much tougher chore when the Fed is on hold or even easing monetary policy. As a result, the alternative way of making dollar-denominated assets more attractive would be to make them appear cheaper via a lower currency rate. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said Wednesday that the central bank doesn’t seek to affect the dollar with its policies, but it’s clear that the international investors have been diversifying away from the greenback. The dollar accounted for 61.9 percent of global currency reserves as of the end of the third quarter, the lowest level since the end of 2013.

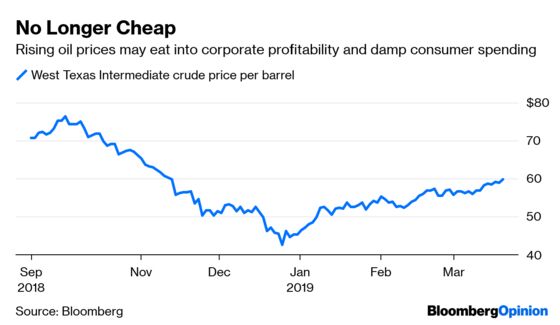

OIL ON THE RISE

Oil briefly rose above $60 a barrel in New York on Wednesday for the first time in more than four months, bringing its year-to-date gain to almost 32 percent. The reason given for the latest increase was a government report showing the biggest withdrawal of crude in U.S. storage tanks since July, a sign of tightening supplies. The 9.59 million-barrel decline in American oil stockpiles reported by the government confounded all 10 forecasts from analysts in a Bloomberg survey, according to Bloomberg News’s Ben Foldy. Although oil remains well below the more than $75 a barrel level reached in early October, the higher prices are likely to take a toll on manufacturers as well as consumers because the economy has decelerated greatly this quarter. In other words, growth may be too sluggish for manufacturers and consumers to easily absorb higher energy prices. Among the most recent evidence of that is government data showing a 0.5 percent drop in personal spending in December, the biggest such decline since 2009.

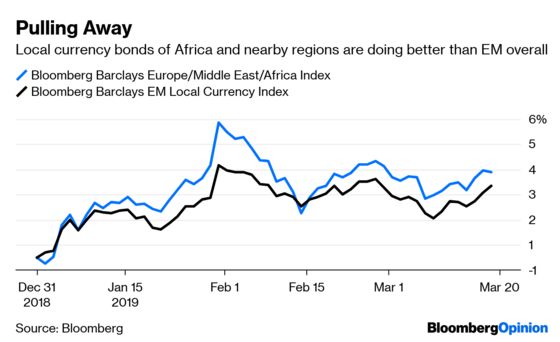

AFRICA RISING

For years, global investors have extolled the promise of Africa. Yes, the continent’s political situation always seems to be in flux, but when looked at holistically, Africa seems to be in an upward trend. At least that’s true economically speaking. The median estimate of economists surveyed by Bloomberg see Africa’s economy expanding by 3 percent this year and 3.7 percent in 2020, up from 2 percent in 2018. This optimism can be seen in several bond sales this week. West African neighbors Benin and Ghana issued a combined $3.6 billion worth of bonds on Tuesday, and met with robust demand from investors, according to Bloomberg News’s Paul Wallace. For Benin, which has annual output of barely $10 billion and is rated four steps below investment grade, the sale was its first foray into the market. Ghana’s bumper sale was even more impressive, with investors looking past its volatile currency and the risk of a fiscal splurge before elections next year.

TEA LEAVES

In what has so far been a good year for emerging markets, the notable exception is Argentina. Its peso has slid 8.26 percent since the end of January, compared with a gain of 2.26 percent in the MSCI EM Currency Index. The peso’s drop in 2019 follows a 50.6 percent tumble in 2018 as Argentina’s economy fell into a recession and its deficits widened. To say that pressure on Argentine President Mauricio Macri is rising would be an understatement. He’s likely to suffer another blow Thursday with the release of fourth-quarter GDP and unemployment data, which are forecast to show Argentina's economy sinking further into recession. The median estimate of economists surveyed by Bloomberg is that Argentina’s economy contracted 6.4 percent in the final three months of 2018, the most since 2009.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.