(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Almost 250 million people live outside their countries of birth, about three times as many as in 1970. Yet few countries have made arrangements for these people’s political representation. That’s a mistake. Correcting it could have led to different results in recent momentous votes in many countries, including the U.S.

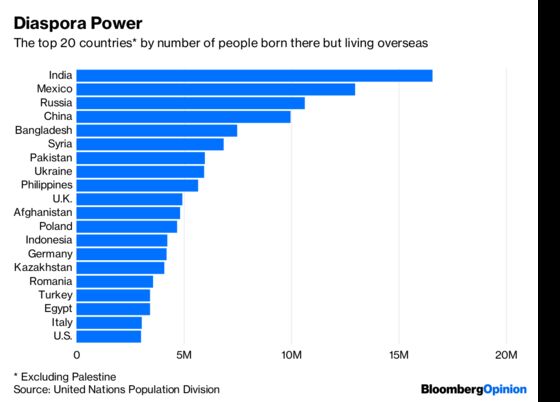

It helps to imagine the diasporas as overseas territories. The Russian one would be the country’s second-biggest region, the Mexican one that nation's second-biggest state. Americans living abroad would form the 32nd-most-populous state, falling between Utah and Arkansas, and overseas Germans would be the county’s seventh-biggest state, right after Saxony.

According to the International Institute for Democratic and Electoral Assistance, 72 percent of nations allow overseas voting in some form. But few treat the diaspora as a separate entity that deserves its own representatives. That doesn’t make sense. Expats, emigres and refugees have specific interests in their home countries as a group. U.K. expats in European Union countries are one example: They see Brexit differently than U.K. residents. Americans are another: As expatriates, they share an interest in avoiding double taxation.

“As a German living abroad, I have other interests than those who permanently reside in Germany,” Ulrike Franke of the European Council on Foreign Relations wrote recently, calling for Germany to introduce diaspora representation. “Other matters concern me. Such as, will Germans in England next require resident permits which will only be granted after a certain income level. I have an interest in close cooperation between the German government and French President Emmanuel Macron. It’s important to me that Germany works on making different European pension and insurance systems compatible so that my pension contributions made in different European countries don’t get lost.”

All diasporas have a strong interest in the foreign policies of their countries of birth — an interest stay-at-home citizens often lack. Russians living overseas have started running into travel, employment and business problems since Moscow turned aggressive. The U.S. diaspora has to live every day with the consequences of President Donald Trump’s foreign policy and the boorish image he’s creating for the U.S.

Most counties attach overseas voters to existing domestic constituencies. If I’d voted in Berlin in the Russian parliamentary election of 2016, my vote would have gone either to Kursk or to Cherepovets, two randomly chosen cities whose local issues are of no interest to me, a Moscow native, and whose elected officials have no interest in representing me as a Russian resident of Germany. Most countries let expatriates vote where they used to live before they moved overseas. Franke’s German parliament member, elected in the city of Aachen, knows nothing of her concerns.

Diasporas Matter

That diasporas often vote in distinctly different ways from those who live in their country of birth is a strong argument for giving them their own representation.

The share of Britons voting to remain in the EU in 2016 was much higher among expatriates than among U.K. residents. Perhaps less predictably, Turks living abroad backed President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s bid for expanded powers in a 2017 referendum by a significantly wider margin than voters in Turkey — 59 percent compared to 51 percent.

In the parliamentary election in Latvia earlier this month, the center-left Harmony party, backed by the country’s Russian minority, came in first with almost 20 percent of the vote; among expats, an increasingly important constituency given Latvia’s shrinking population, only 6.5 percent backed Harmony while 35.7 percent cast ballots for the populist party KPV LV. Latvian expats voting in the U.K. displayed a similar pattern to that of the Brexit referendum, with populist support lower among Latvians living in London.

Few governments, political parties or even academics bother to study the motivations behind distinctive expatriate voting patterns. Campaigning in the foreign constituencies isn’t widespread, either, although Erdogan’s political machine has recently worked hard to collect the overseas vote. Despite the consternation his campaigning has caused in Germany and the Netherlands, more politicians should follow his example. Treating expat voters as an afterthought makes little sense. They can decide election outcomes.

Overseas ballots were the subject of ferocious partisan combat in the 2000 U.S. presidential election and were counted in Florida in a way that helped put George W. Bush into the White House, according to an exhaustive post-mortem by the New York Times. In 2005, a center-left candidate in the Croatian presidential election was forced into a runoff by expatriates voting for the nationalist party. In 2006, the votes of Italians abroad ensured center-left technocrat Romano Prodi’s victory over incumbent Silvio Berlusconi.

It’s interesting to imagine how diasporas could swing important elections if they’d been more empowered and if campaigns had made more of an effort to engage them. They could have produced a different outcome for the Brexit referendum, for example. More than 135,000 Britons registered as overseas voters ahead of that ballot, bringing the total number of expat voters to 264,000. But almost 5 million British-born people live abroad, and Leave won the referendum by a margin of about 1.3 million.

A Political Home

Expats might bother to vote more diligently if they had their own representatives in the home country’s parliament.

The U.K. has considered and rejected the idea. There and in most other countries (but not in the U.S., which taxes its expatriates) it would go against the “no representation without taxation” principle. But a handful of countries aren’t bothered by that: Expats, after all, can come back, and it pays for a country to maintain a connection to these mobile, enterprising citizens.

Most of the countries that have set up expat constituencies have produced relatively large diasporas. In Africa, these are Algeria, Angola, Mozambique and Cape Verde. In the Americas: Colombia, Ecuador, the Dominican Republic and Panama. In Europe: France, Italy, Portugal, Croatia, Romania and Macedonia.

The French system, Europe’s oldest, has existed, with revisions, since 1948. It’s somewhat unwieldy. French people living overseas elect a special 150-member council to represent them before the French government, and that body selects 12 senators to serve in the upper house of the French legislature. The expats also directly elect 11 members of the lower chamber; currently, eight of them are from Macron’s political party.

In the other European countries that allow diaspora representation, the elections are direct and there are fewer constituencies. Portugal, for example, has two — one for Europe and another for the rest of the world, and Italy has four, representing Italians in Europe, North and Central America, South America and the rest of the world.

In Portugal, Croatia and Macedonia, the number of legislators elected abroad depends on the turnout, to make sure they don’t represent fewer people than their colleagues elected at home. That’s a useful safeguard. In Croatia, for example, a maximum of six seats can be won from the overseas electoral district, but only three were distributed in the 2016 election because only 21,208 people voted out of an expat community estimated by the United Nations at more than 900,000 people (though some of them have given up Croatian citizenship). And in Portugal, only about 12 percent of the 242,849 registered expatriate voters cast ballots in the 2015 legislative election.

And yet foreign turnouts can be relatively healthy. In this year’s Italian parliamentary election, almost 1.3 million expats cast votes, 30 percent of all voters registered as living abroad. That activity is understandable given the important role the foreign community’s representatives can play in Rome. In his 2013 book, “The Scramble for Citizens,” the sociologist David Cook-Martin recalled how in 2007, Luigi Pallaro, elected to the Italian Senate in South America, cast the decisive vote in a confidence vote on the Prodi cabinet. The government he saved was grateful, accepting his proposal that 52 million euros ($60 million) be allocated to Italian communities abroad in the next two years.

In this year’s Italian election, the mainstream, center-left Democratic Party finished first among the expatriates; nationwide, the populist Five Star Movement did. The diaspora didn’t prevent an anti-establishment revolution, but at least it tried.

It would be interesting to contemplate how the U.K. Parliament or the U.S. Senate would function if they included representatives of expatriate communities. It’s not such a crazy idea: The Democratic Party, for example, recognizes Democrats Abroad as a “state” for presidential primary purposes.

One could imagine anti-Brexit expat representatives scuppering Prime Minister Theresa May’s parliamentary majority, or Democrats representing the expat “state” making sure that Brett Kavanaugh didn't make it onto the Supreme Court.

Modern nations aren’t confined to their geographic borders. Leaving one’s country for extended periods is no longer unusual, and it shouldn’t mean breaking off civic ties. In his 2013 book, “Parliament and Diaspora in Europe,” Michel Laguerre of the University of California at Berkeley described the countries that allow diaspora representation as “cosmonations.” In a sense, every nation is a cosmonation today: It’s a reality waiting to be recognized by conservative, hard-to-reform political systems.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jonathan Landman at jlandman4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European politics and business. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.