Europe’s Rebound Shows Draghi Got it Right

Better-than-expected economic data vindicates the ECB’s decision to offer only a limited stimulus package in March.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The European Central Bank faced a torrid start to the year, as critics said it was not providing enough stimulus to a slowing euro-zone economy.

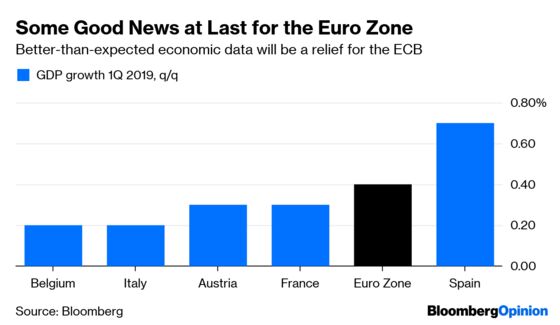

In retrospect policy makers may have got it just right. The economy in the currency union expanded by 0.4 percent in the first quarter, beating expectations. The growth rate may not be spectacular, but is higher than in the last three months of 2018, when it came at 0.2 percent. The euro zone is not out of the woods yet, but the ECB’s wait-and-see approach may have been vindicated.

For much of the first quarter, the central bank could not really make up its mind about the extent of the region’s slowdown. President Mario Draghi noted how the industrial sector was clearly going through a rough patch courtesy of a range of one-off factors (including disruptions in Germany’s automotive sector) and global trade tensions. The question was whether these weaknesses would impair internal demand.

The data from the first quarter show that euro-zone factories are back. Italy’s emergence from a technical recession was probably the result of a rebound in manufacturing and entirely due to exports — the economy expanded 0.2 percent in the first quarter compared to the final three months of last year. In France, where the economy grew 0.3 percent, manufacturing accelerated significantly. In Spain, production bounced back strongly from a poor second half in 2018, driving a 0.7 percent increase in gross domestic product.

Meanwhile, there is no sign that the labor market is getting weaker: The region’s unemployment rate fell to 7.7 percent in March from 7.8 percent in February, hitting the lowest level in more than ten years.

These improvements, alongside rising wages, will continue to help the services sector, which is more dependent on domestic spending. The vicious circle Draghi feared between external conditions and internal demand may have stopped just in time.

This allows a reassessment of the announcements the ECB made last March to stimulate the economy. These included a new round of cheap loans to the banks and the decision to delay the first hike in interest rates to at least the start of 2020.

This set of measures was probably stingier than what it might have been, and did not include some crucial details such as the price of the loans. There was also no sign that the ECB might want to revive asset purchases after ending them in December. This package now looks broadly adequate and is unlikely to need further adjustments when the governing council meets again in the coming months.

Still, the ECB should be as generous as it can be within the limits policy makers have set themselves. There are signs that inflation is coming back, as price pressures in Germany in April vastly exceeded estimates. Yet these were largely due to one-off factors, partly driven by the timing of Easter. Core inflation in the euro zone, which strips out more volatile items such as energy and food, remains well below the central bank’s target of just under 2 percent.

The outlook also remains uncertain. In Italy the government, including finance minister Giovanni Tria, seized at the news that the country had resumed growth to say that this proved the “solidity” of its economy. But the prolonged weakness of internal demand, alongside a deeply uncertain fiscal outlook, are a reminder that Rome remains the sick man of the euro zone — and a cause of concern for its partners. The German economy, while much stronger than Italy’s, is also a big question mark, as its manufacturing sector continues to stutter.

In exactly six months, a new president will take office at the ECB. The mild improvements in the euro-zone economy might be enough for Draghi to breathe a small sigh of relief as he comes close to his exit at the end of October. They should be in no way sufficient to calm down his successor, whoever he or she might be.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jennifer Ryan at jryan13@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Ferdinando Giugliano writes columns and editorials on European economics for Bloomberg Opinion. He is also an economics columnist for La Repubblica and was a member of the editorial board of the Financial Times.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.