(Bloomberg Opinion) -- U.S. senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren has released a bold plan for college affordability. The proposal has three basic components — making public universities free, providing more funding for historically black colleges and universities, and cancelling large amounts of student debt.

The idea of free public universities is something I’ve argued against in the past. Warren’s plan would use government funding to replace the lost tuition, but this system might not allow universities to increase their expenditures in the future to meet the needs of research or educational-quality improvements. It would also make them politically vulnerable to budget cuts. In the long term, this could compromise the quality of the U.S.'s public universities, which are now among the world’s best. It could also encourage universities to shift admissions toward kids from well-off families who tend to make large alumni donations — exactly the opposite of what the system needs. A better idea would be to expand financial assistance and admissions access to young people from disadvantaged backgrounds, and make community colleges free.

Warren’s plan for HBCUs, in contrast, is a good one. These institutions are better than most universities at encouraging social mobility, because they mainly serve poor black students who otherwise might not attend college, and who have the most room to better their economic situation. But these engines of economic advancement are struggling financially, and Warren’s plan would give them a needed boost.

But the centerpiece of Warren’s plan — and the part that will undoubtedly be the most hotly debated — is the student-loan forgiveness program. Warren wouldn’t forgive all student debt; instead, she would offer relief only for those whose outcomes in the labor market weren’t so spectacular. Under her plan, people making less than $100,000 would be able to get as much as $50,000 of loan forgiveness, while people making $100,000 to $250,000 would be able to get partial relief. Above the $100,000 cutoff, every additional $3 of annual income would reduce loan forgiveness eligibility by $1. People making more than $250,000 would thus get no loan forgiveness at all.

This scheme is similar to another idea that has long been used in Australia and is growing more popular in the U.S. — income-based repayment of college loans. The idea is that the less you earn, the less you have to pay. If you never end up earning very much, you never end up paying very much. In other words, it makes student loans less like debt and more like equity.

Income-based repayment has a number of advantages. It’s more egalitarian, because it imposes less of a burden on low-income people with debt. It aligns the incentives of borrowers and lenders — very few borrowers would intentionally make less money just to get out of having to make lower debt payments. And it forces lenders to consider whether the education they’re financing will actually help the student in question, which would help reduce demand for schools (or majors) that don’t do much to boost their graduates’ labor-market outcomes.

Warren’s plan would essentially impose income-based repayment retroactively. It’s not quite as elegant as real income-based repayment plans, since it’s based on current income rather than lifetime income. But it retains the basic principle of egalitarianism — requiring less from people whose outcomes weren’t as good. And it would help get the debt relief to those who need it most — people who want to start a business or move to a better job, but who are imprisoned in their current jobs by the need to make monthly loan payments. It would also give more relief to those whose career trajectories were permanently injured by the Great Recession.

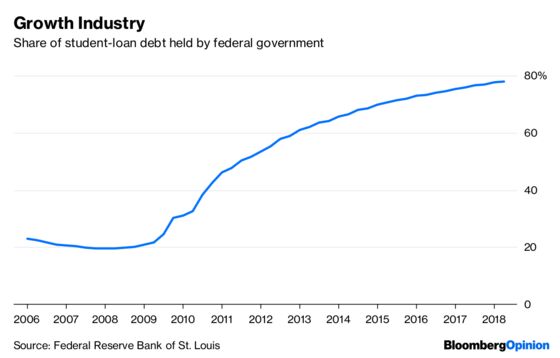

The $640 billion cost of the plan would fall on the U.S. taxpayer, since most student loans are now owned by the federal government:

Some privately held student debt would also be cancelled, but Warren suggests that the government would pay for much of this as well. Since most taxes are paid by higher-earning Americans, this makes the Warren plan redistributive, which is good given the U.S.’s very high levels of inequality.

Critics of Warren’s plan will argue that it’s unfair, since people who worked hard to pay back their loans will get no relief. That problem could be solved by mailing checks to those people equal to what they would have received in loan relief if they hadn’t paid back the loans. But in any case, the imperative of fixing the student-debt problem, which is probably exerting a drag on economic growth, overrides the legitimate concerns about fairness.

A bigger concern is moral hazard. If future students expect their loans to be cancelled, it could lead to more borrowing in the future, which would further push up college tuition and leave the country with an even bigger problem down the road. The solution is to make income-based student loan repayment universal. Combined with free community college, programs to make college more affordable for low-income students, and measures to control cost growth at universities, that should remove the necessity for Warren’s debt cancellation to be repeated in the future.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.