(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Germany is celebrating its national holiday on Wednesday. Yet this year, German Unity Day is less of a festive occasion. It’s been 28 years since the Berlin Wall came down, but a kind of invisible wall still separates the country’s east and west. For the first time, the nationalist Alternative for Germany (AfD) party is ahead of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union in polls taken in the ex-Communist eastern states.

Even though the economic gap between the country’s east and west has shrunk in the 28 years since reunification, the political chasm is widening. The east is swinging to the far right because many of its people still feel like second-class citizens, and the recent arrival of hundreds of thousands of immigrants has only intensified their sense of being abandoned by reunified Germany's mostly western establishment.

TWO ECONOMIES

The German government has published a report on the progress of unification every year since 1997. The headline numbers show staggering economic improvement.

The per-capita economic output in the eastern states and Berlin was only 43 percent of the western level in 1991. That number rose to 73 percent in 2016. An eastern household’s average disposable income stood at 61 percent of the western level in 1991 and at 85 percent in 2016. Unemployment at the end of last year reached 5.3 percent in the west and 7.6 percent in the east. That was a huge change from the first years after reunification, when the number of jobs available in the former East Germany decreased by 34 percent between 1989 and 1992, causing joblessness in the east to jump from zero percent to about 15 percent, twice the western level.

It’s only natural that differences remain -- nobody expected them to disappear within one generation’s lifespan.

Eastern Germany’s output and income data look great compared with other post-Communist nations’. The Czech Republic, the wealthiest of them, had 45 percent of Germany’s per-capita gross domestic product and about 60 percent of eastern Germany’s.

By the end of next year, Germany will have pumped 156 billion euros ($180 billion) of targeted government subsidies under the so-called Solidarity Pact into the “new states” since 2005. That doesn’t include private investment by companies taking advantage of the east’s cheaper labor. Overall, the collapse of communism has worked out better for the ex-GDR than for other former Soviet satellites that have joined the European Union.

Still, some aspects of the remaining economic gap between Germany’s east and west are alarming. Above all, the east is barely catching up anymore. In the last 10 years, the west-east difference in per-capita GDP has only shrunk by 4.2 percentage points. The disposable income difference has held relatively steady since 2000. And east German business hasn’t really caught up as much as the headline numbers would suggest.

For example, per-capita industrial output in the east is only 52 percent of the western level, a vast improvement over the 17 percent registered in 1991, but still a lot of distance yet to cover. East German firms’ exports account for 36 percent of sales, compared with almost 49 percent for west German companies. In an export-oriented economy like Germany’s that’s a telling difference.

The reason is that in the east, businesses are on average smaller than in the west; they spend about half as much on research and development as a percentage of sales, have only 74 percent of the labor productivity (78 percent if Berlin is included), pay lower salaries and don’t drive infrastructure development as much. Even internet speeds are slower in the east.

That may never change; in the 28 years since reunification, not a single German multinational has placed its headquarters in the new states.

TWO NATIONS

East German men live, on average, to 77.2 years, about 18 months less than west German males, yet the population of the east is older than in the west. That’s due to a long-term depopulation trend: The east accounted for 18.3 percent of Germany’s population in 1991, down to 15.2 percent today.

Young people face economic pressure to keep leaving: Youth unemployment in the east, at 8.4 percent, is still about twice the western level, even though the general unemployment gap has shrunk. Though, statistically speaking, east-west migration has stopped, only Berlin, its surrounding state of Brandenburg and Saxony attract more people from the west than they lose to it; the other three eastern states still have negative domestic migration rates.

But the most glaring differences between the people who inhabit the two parts of Germany are in the way families function. About 39 percent of east German women with kids under three years-old hold down full-time jobs, compared with 19 percent in the west. A full quarter of eastern families and just 17.5 percent of western ones are single-parent households.

These dissimilarities can’t be attributed to the east’s relative economic backwardness, but rather to cultural differences, research has shown. In the former East Germany, where gender equality was a policy goal before the West warmed to the idea, women were more inclined to work full-time even when they had small children; they trusted the state to take care of the kids in the meantime, and they didn’t rely as much on male partners. This attitude appears to have been passed down to the next generations. The easterners still have a strong cultural preference for egalitarianism: There is still less economic inequality in the eastern states than in the west.

The relative unhappiness of east Germans is probably due to a combination of economic and cultural factors. And while a majority of westerners feel they have something to celebrate on German Unity Day, a minority of easterners feel like joining in.

TWO SOCIETIES

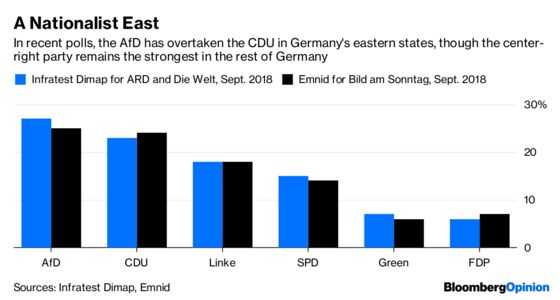

The economic, social and cultural gaps naturally result in different voting patterns; Die Linke, the successor party to the GDR’s Communists, has historically done much better in the new states than in the west. But the combination of slightly lower incomes, less favorable demographics and a lasting Communist heritage cannot quite explain the right-wing AfD’s rise to first place in polls. Nor can the generally declining popularity of the fractious ruling coalition of Christian Democrats and Social Democrats. In the west, according to a recent Infratest Dimap poll, the coalition remains popular.

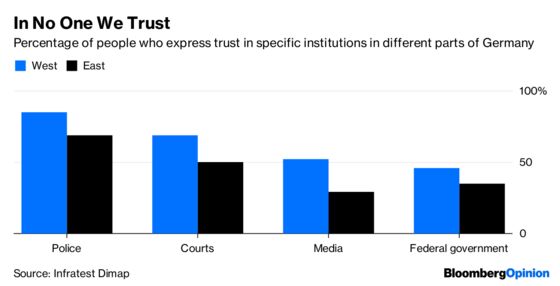

Two factors are likely most responsible for the nationalists’ ascendancy in the east. One of them is the easterners’ greater mistrust of the system and its institutions: the police, courts, media and federal government.

This is not merely part of the Communist legacy, which undermined confidence in institutions in all post-Communist countries. East Germans are unique in having an excellent reason to treat the authorities as alien to them. In the years since their country was swallowed up by its wealthier, democratic neighbor, the number of easterners at the top levels of government, the justice system and corporate hierarchies has barely increased. Last year, no top federal judges, only 1.6 percent of the top managers of companies included in Germany’s DAX stock index, 1 percent of generals and admirals and 7 percent of cabinet ministers in easterner Merkel’s cabinet were from the east.

This is such an extreme case of non-representation that quotas for east Germans have been suggested. No wonder any party that styles itself as anti-elite can do well in the east.

The popularity of an anti-immigration party like AfD also makes sense. Traditionally, Germany’s east has had a low share of immigrants: about 7 percent in the new states, compared with 12 percent in the former West Germany.

In the past, the xenophobia in the east was fueled by a paucity of contact with foreigners. Now, there may be too much. Germany took in 1.2 million asylum seekers in 2015 and 2016. They were distributed among states more or less according to their population and economic well-being. But the east had more empty housing. Eastern Germany excluding Berlin took in 20.7 percent of the asylum seekers, more than its share of Germany’s population. Coupled with the longstanding mistrust of “others,” this almost certainly helped the AfD as the party exploited Germany's fears about “Islamization.”

To the rest of Germany, the AfD is a dangerous political force that should be watched by the domestic intelligence service like other radical organizations; 66 percent of westerners would like that. In the east, only 48 percent would favor such a measure because the AfD is viewed as a legitimate party trying to right wrongs that the western-led system ignores.

The east, of course, is a relatively small part of Germany, and its political preferences aren’t decisive on the national level. But that only serves to perpetuate the country’s division. Reiner Haseloff, the first minister of the eastern state of Saxony-Anhalt, said recently that the border between east and west “cannot be smoothed out even in the next 100 years.” For his party, the CDU, that’s way too long to wait: The political force that brought about Germany’s reunification is quickly losing ground in the east. And as the government phases out a special tax to support the new states next year, since presumably they have caught up enough, it’ll have even less leverage there.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Max Berley at mberley@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European politics and business. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.