(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Some U.S. cities have seen their fortunes rise in the new economy. Technology hubs such as San Francisco and Seattle, as well as coastal metropolises like New York and Los Angeles, are thriving. But some less-glamorous cities — especially in the Midwest — have been struggling. St. Louis isn't the worst off, but it’s definitely in the latter category.

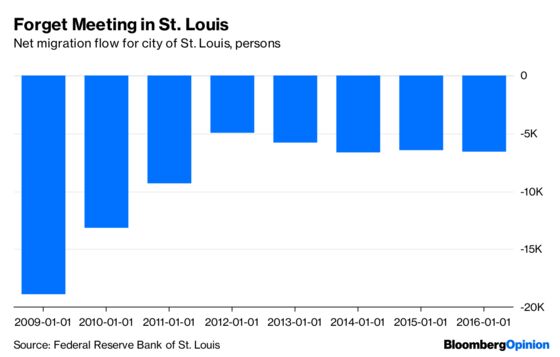

The numbers aren’t all bad. Unemployment in St. Louis is low — only about 3 percent. Poverty in the city has fallen slightly, though at 25 percent it’s still very high. But people are still streaming out of the city (which may be one reason for the low unemployment rate:

Besides poverty, one of the reasons for the population loss might be social ills. St. Louis is a violent city, with a murder rate of more than 60 per 100,000, more than 18 times the rate of New York. In 2017 the city was shaken by riots and protests over police brutality — during the protests, police mercilessly beat a black undercover officer whom they mistook for a protester.

Businesses are leaving the city as well. In 1980, St. Louis was home to the headquarters of 23 Fortune 500 companies; as of 2018 it was only 10.

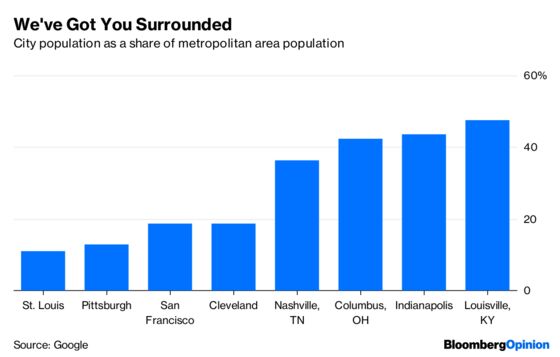

The city has rallied gamely to the challenge of Rust Belt decline, attempting to lure skilled workers to town with a revitalized downtown and the prowess of Washington University of St. Louis, especially the latter’s high-ranked medical school. But a local think tank has a big idea to speed the revival — a merger between the city of St. Louis and the neighboring St. Louis County. A unified city would be the 10th largest in the U.S by population.

Consolidation seems like an obvious move to anyone who has spent considerable time in the St. Louis area (as I have, since much of my extended family lives there). The city of St. Louis represents only about 11 percent of the population of the metropolitan area, an unusually low share:

Ever since the so-called Great Divorce that separated the city of St. Louis from St. Louis County in 1876, the metropolitan area has been a crazy patchwork — it now comprises almost 100 independent municipalities and unincorporated Census areas. Each of those little suburbs has to have its own police department, courts, taxation system and governing administration.

Each one also has to have its own development strategy. In their book “Our Towns: A 100,000-Mile Journey into the Heart of America,” James and Deborah Fallows illustrate how some struggling cities have been able to revive their economies with a combination of industrial policy, human capital development, cooperation with universities and nonprofits, downtown revivals and smart branding. With 100 tiny towns both duplicating efforts and working at cross purposes, the St. Louis metro area won’t easily be able to coordinate on such a strategy.

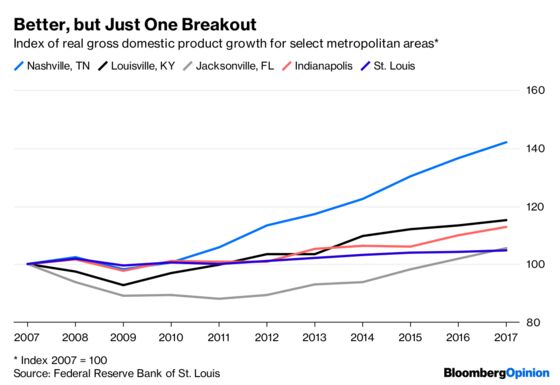

The idea of consolidation isn’t without precedent. Several other midsize cities have merged with their surrounding counties — Nashville, Tennessee; Jacksonville, Florida; and Indianapolis back in the 1960s and '70s, and Louisville, Kentucky, in 2003. All of those metropolitan areas seem to be doing better economically since the financial crisis, though Nashville is the only one whose growth has been spectacular. Notably, all have outpaced St. Louis:

Meanwhile, other cities that have annexed surrounding areas often seem to be doing well. The divergence in performance between thriving Columbus, Ohio, and struggling Cleveland might be related to the fact that Columbus has annexed much of its metropolitan area, while Cleveland remains a small city at the center of a suburban patchwork. Of course, there are probably other factors at work — Ohio State University in Columbus is much larger than Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. But the pattern is interesting nonetheless. Meanwhile, although it never completed a formal merger, Minneapolis and St. Paul — two of the Midwest’s most successful cities — have a program for sharing tax revenue among the various municipalities in the metropolitan area.

The evidence on city-county consolidation is mixed, with some studies showing benefits, others finding negative impacts and still others finding little effect. Furthermore, it’s hard to evaluate the direction of causality, since cities that successfully consolidate with their counties might do so because they’re doing well economically in the first place. It also might be the case that consolidation wasn’t very effective in the mid-20th century, but is more helpful now — the big shift from a manufacturing-based economy to a knowledge-based one, which has powered the urban revival, could have changed the calculus.

In any case, given St. Louis’ uncommon and pathological level of fragmentation, and the successes of places like Columbus, Nashville, and Minneapolis-St. Paul, consolidation seems like a good thing to try. And St. Louis’ experiment could serve as a trial for other struggling, fragmented cities like Cleveland.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.