Beijing Dithers as the Economy Declines

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- China’s annual economic policy summit has come and gone, leaving a wet lump of coal in place of stimulus hopes. Beijing will have to do better if it wants to steer the country to another year of robust growth.

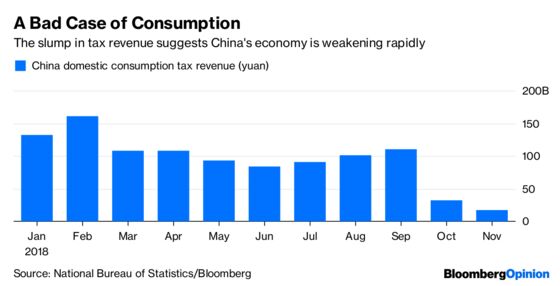

The economy started slowing in September, and has only worsened since then. Consumption tax revenue was up 16.3 percent year-to-date as of that month. In the following two months, it collapsed, recording declines of 62 percent and 71 percent from a year earlier. Value-added tax revenue has also turned negative in the past three months. All this is a good sign that the economy’s deterioration is more rapid and pronounced than the government has acknowledged.

Against this backdrop, the Central Economic Work Conference convened earlier this month. Beijing made news by not making any news at all. No new stimulus packages were announced. Monetary policy will be kept stable and prudent, Xinhua reported after the meeting ended. Confusion surrounds real-estate policies after officials announced some cities would be allowed to ease sales restrictions, only to backtrack a day later, emphasizing Beijing’s intention to control prices.

So what are the challenges facing China in 2019 and how do authorities plan on meeting them?

Beijing has done an admirable job of starting the long-promised deleveraging process. The economic slowdown reflects a sharp tightening of credit that began in November 2017, the month after President Xi Jinping’s reappointment for a second term as leader. It took a six-to-nine-month pass-through period for that squeeze to be felt.

However, 2019 will be where the reality of economic pain meets calls for more credit. Beijing is trying to negotiate an end to the U.S.-China trade war as internal opposition to the conflict gains momentum. The dispute has sapped confidence within China and is pushing the government to consider painful market-opening concessions.

The trade negotiations have probably delayed Beijing’s response to the economic downturn, as officials wait to see what concessions they may have to make (the U.S. and other countries are pushing for verifiable changes to Chinese protectionism and overseas investment). With reports of a weak job market and falling asset prices, their indecision becomes more problematic each day.

Unfortunately, authorities have far fewer tools at their disposal this time. The government wants to avoid being seen as flooding the market with credit to prop up growth as it did in 2009-2011 and 2016-2017. However, monetary easing also raises problems as yields are already near parity with those in the U.S., raising outflow pressures on the yuan. Furthermore, there is evidence potential tax and interest rate cuts will be less stimulative than in the past as more of the increased income is saved.

Finally, Chinese banks are under enormous pressure. Bank of China Ltd. has announced plans to sell as much as 40 billion yuan ($5.8 billion) of perpetual bonds; other banks are considering raising 100 billion yuan each. Only in November, the central bank’s financial stability report declared Chinese bank capital “abundant.” With new loans outpacing new deposits by 13 percent in 2018, how the government recapitalizes a strained banking sector will be a major theme in the coming year. This matters because authorities will struggle to carry out fiscal stimulus as long as banks are capital-constrained.

Stimulus would provide some short-term relief, though at the cost of setting back a deleveraging process that’s essential to the Chinese economy’s long-term health.

Every year the challenges for Beijing get bigger, yet the responses only delay the reckoning rather than addressing the problem. Never underestimate China’s ability to sustain growth, but don’t expect solutions. Increasingly expensive palliatives look the more likely route in 2019.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Christopher Balding is a former associate professor of business and economics at the HSBC Business School in Shenzhen and author of "Sovereign Wealth Funds: The New Intersection of Money and Power."

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.