(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The November 1971 Senate Judiciary Committee confirmation hearings for Lewis F. Powell Jr. were a placid affair. Republican President Richard Nixon had nominated Powell for the Supreme Court at the same time as William H. Rehnquist, who as a lawyer in private practice in Phoenix in the 1950s and 1960s had been a vocal opponent of civil rights legislation. Powell — a longtime partner at the law firm now known as Hunton Andrews Kurth in Richmond, Virginia, a member of multiple corporate boards of directors, including that of tobacco giant Philip Morris (now Altria Group Inc.), and a former president of the American Bar Association — was by comparison an uncontroversial choice. The legislative director for the AFL-CIO summed up the perceived contrast in his testimony to the committee, calling Rehnquist a “right-wing zealot” and Powell “thoughtful, scholarly and moderate.”

To a great extent, that was right. Powell was a moderate on lots of issues, and he was certainly careful and considered in what he said in public. But there was one important issue he was quite zealous about, and it might have been of interest to the AFL-CIO and several of the senators on the committee. It was the subject of an impassioned confidential memo that Powell had sent to the leadership of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that August.

“No thoughtful person can question that the American economic system is under broad attack,” he began, before urging business in general and the Chamber of Commerce in particular to become much more politically active, to pursue their interests with more vigor in the courts, and to openly confront campus radicals and “perhaps the single most effective antagonist of American business,” consumer advocate Ralph Nader.

While neither responsible business interests, nor the United States Chamber of Commerce, would engage in the irresponsible tactics of some pressure groups, it is essential that spokesmen for the enterprise system — at all levels and at every opportunity — be far more aggressive than in the past.

There should be no hesitation to attack the Naders, the Marcuses and others who openly seek destruction of the system. There should not be the slightest hesitation to press vigorously in all political arenas for support of the enterprise system. Nor should there be reluctance to penalize politically those who oppose it.

“Marcuses” refers to Herbert Marcuse, a leftist philosopher who was teaching in those days at the University of California at San Diego. The notion that he and Nader posed an existential threat to American capitalism now seems quite far-fetched, although I guess it’s easy to say that now. Things surely looked different from the perspective of 1971; plus, Powell did do his part to thwart the threats he perceived. Describing Nader as someone who sought “destruction of the system,” though, does seem like it was obviously incorrect even then.

Not that any of this came up at Powell’s Supreme Court confirmation hearing! The memo wasn’t made public until almost 10 months after the majority-Democratic Senate approved his nomination by an 89-1 vote (the lone dissenter was populist Oklahoma Democrat Fred R. Harris, who called Powell “an elitist” who “has never shown any deep feelings for little people”). Syndicated columnist Jack Anderson published excerpts in September 1972 and called the memo “so militant that it raises a question about [Powell’s] fitness to decide any case involving business interests.” The Chamber of Commerce then released the whole thing in an attempt to show “that it objectively and fairly deals with a very real problem facing the free enterprise system,” and the storm died out after that.

The Powell memo has returned to prominence in recent years thanks to books, articles and an apparently influential PowerPoint deck that have portrayed it as a, or even the, founding document of the modern conservative movement. That seems to be, as the New America Foundation’s Mark Schmitt argued a couple of years ago, a stretch. Powell’s words did help energize the Chamber of Commerce, which became more politically active and strident and launched a highly effective litigation arm, but most of the modern conservative infrastructure can be traced to other roots. In fact, some of that infrastructure sprang up in opposition to decisions Powell joined in while on the Supreme Court. He was, the New York Times wrote when he retired from the court in 1987, a “determined moderate who has provided the critical fifth votes in key Supreme Court rulings for abortion rights and affirmative action.”

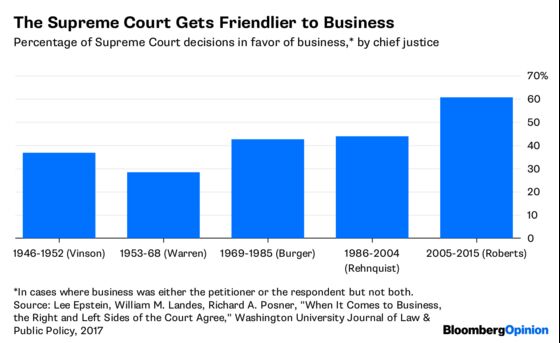

That Times article made no mention of Powell’s votes on business and campaign finance matters. But recent events and research have showed these to be perhaps his most important legacy. Supreme Court voting patterns took a marked pro-business lurch in the years after Powell joined, and this was not a coincidence.

These data are from a paper published in 2013 and updated last year by political scientist Lee Epstein, economist William M. Landes and since-retired U.S. Court of Appeals Judge Richard A. Posner that tallies the Supreme Court votes and decisions from 1946 through 2015 in cases “in which a business entity was either a petitioner or a respondent but not both.” Epstein, Landes and Posner also ranked 36 justices who served during that period by the percentage of these decisions in which they sided with business. Powell had the 10th-highest business-friendliness score, which doesn’t sound all that impressive until you consider that:

- All the justices with higher scores served either after or well before him (the list is currently topped by Samuel Alito and John Roberts).

- The man he replaced on the Supreme Court, Hugo Black, was arguably the most business-unfriendly justice of the post-1946 era, coming in ahead of only two relatively short-tenured justices in the vote ranking.

That “right-wing zealot” Rehnquist, meanwhile, came in well below Powell for business-friendliness, and also below the justice he replaced, John Marshall Harlan II. It was the Black-for-Powell swap that did the most to shift the Supreme Court vote balance toward business during the tenure of Chief Justice Warren Burger, followed by Burger’s replacement of Earl Warren and John Paul Stevens taking the place of William O. Douglas.

Meanwhile, Powell seems to have played the decisive role in the Supreme Court’s unleashing of wealth and corporate power in the political arena — or, more accurately, its re-unleashing after seven decades during which the courts allowed lawmakers to restrict political activity by business. He was one of three justices who endorsed all of the landmark 1976 per curiam ruling (that is, a group opinion not attributed to a single justice) in Buckley v. Valeo that declared limits on political spending by individuals to be unconstitutional restrictions on free speech but upheld limits on contributions to candidates, then authored the 1978 majority opinion in First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, which for the first time extended First Amendment free-speech protections to corporate political activity. William Rehnquist wrote the dissent (of course!), arguing that:

A State grants to a business corporation the blessings of potentially perpetual life and limited liability to enhance its efficiency as an economic entity. It might reasonably be concluded that those properties, so beneficial in the economic sphere, pose special dangers in the political sphere.

First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti only applied to ballot initiatives, not donations to candidates, but in 2010, Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission swept aside that caveat and effectively banned lawmakers from restricting political spending by corporations.

The author of the majority opinion in Citizens United was Anthony Kennedy, who succeeded Powell on the court in 1988 and also took over his role as social moderate with a pro-business bent. Now Kennedy is to be replaced, if the Senate goes along, by his former law clerk Brett Kavanaugh, who may end up fitting the same profile, although it is of course hard to tell at this point.

So … one story here is just that the future is usually difficult to predict, and sometimes even when it shouldn’t be, people just miss what’s in front of their noses. Despite the fact that Powell had served on 11 corporate boards, hardly anybody in the Senate in 1971 (except perhaps Fred Harris) seems to have sensed that his appointment might mark a sea change in the Supreme Court’s attitude toward corporate America. Meanwhile, far from destroying the American economic system, as Powell feared, Ralph Nader ended up helping Republican George W. Bush get elected president in 2000. Bush then gave Brett Kavanaugh a job at the White House and later appointed him to the federal judgeship that paved the way to his nomination to Powell’s old Supreme Court spot. That definitely wasn’t in the Powell memo.

Another story is that the Supreme Court really has gotten super-duper-friendly to business interests in recent years, and there’s no sign that this will abate anytime soon. You may think business-friendliness sounds like a good thing, but as economist Milton Friedman once put it, “You must distinguish sharply between being pro-free-enterprise, which I am, and being pro-business, which I am not.” There’s a good case to be made that the Supreme Court’s key business rulings in recent years have tended more toward the latter than the former.

In a 2015 essay that I’ve cited before, Harvard Law School professor (and former corporate lawyer) John Coates argues that the man he refers to as “constitutional entrepreneur Justice Lewis Powell” enabled a “corporate takeover of the First Amendment” that is endangering free enterprise and risks turning the U.S. into “a country like Russia that combines both despotism and economic malaise.” In an important new book that I’ve just finished reading, “We the Corporations: How American Businesses Won Their Civil Rights,” University of California at Los Angeles law professor Adam Winkler isn’t quite that hard on Powell or dramatic about the consequences, but he similarly leaves the impression that the Supreme Court’s take on corporate rights has gotten way too expansive. Perhaps this is something that ought to come up in Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.