Bond Traders Love the Fed. The PBOC? Not So Much

Just when Fed is buying U.S. corporate bonds and stabilising markets, PBOC appears to be engineering money market chaos.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Traders are getting grumpy. Just when the Federal Reserve is buying U.S. corporate bonds and stabilizing markets, the People’s Bank of China appears to be engineering money market chaos without a clear policy agenda.

Even amid a global market meltdown this spring, investors kept their faith in China. While a quarter of U.S. junk bonds got downgraded by Moody’s Investors Service in April, that figure was just 13% in Asia, data compiled by Bank of America Merrill Lynch show.

You’ve got to give China some credit for getting money flowing. Property developers, which account for over half of Asia’s high-yield universe, started seeing easier financing back home. After all, the arch of any debt curve bends toward central bank policies. In time of distress, Beijing could keep a steady hand, many hoped.

But now traders are sitting at their desks, staring into thin air. It’s no longer clear what the PBOC is up to. They wonder if the two-year onshore bond-market bull run is coming to an end.

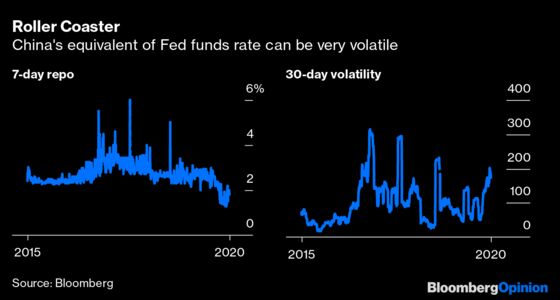

Just take a look at how volatile China’s equivalent of the Fed funds rate has been lately. In just one month, the 7-day repurchase rate, or the short-term rate that banks use to lend to each other, jumped 50 basis points to 1.8%.

This is partly the result of a crackdown on interest rate arbitrage. Since the virus outbreak, billions of dollars of easy money have stayed in the financial system, rather than flowing to the real economy, the central bank discovered. Much of it wound up in so-called structured deposits, a form of high-yielding wealth management product, which have ballooned by over 2 trillion yuan ($282.1 billion) in the first four months of the year. Instead of paying salaries or shoring up working capital, large corporations have been taking out cheap bank loans and issuing low-yielding bonds to get juicy returns instead.

While bond yields fell amid the pandemic, those offered by wealth management products held up. Regional banks and other financial institutions were borrowing heavily in the easy-money repo market, which means those steady yields were only achieved through high leverage. By guiding repo rates back up to make such borrowing more costly, the PBOC can stamp out this carry trade, the thinking goes.

Consider, too, that China operates with a loose interest rate corridor. The ceiling is the rate at which banks can borrow from the PBOC through its standing lending facilities, and the floor is the rate paid on lenders’ excess reserves held at the central bank. Officials aim to keep the 7-day repo rate, which is managed via open-market operations, at the middle of the range. But lately, the corridor has collapsed. Perhaps it’s time to bring the repo line back up, the PBOC reasons.

In the first two weeks of June, the central bank has been tightening its fist, pulling a net 250 billion yuan from the banking system. On Monday, the interest rate offered on its medium-term lending facility remained unchanged, signaling the PBOC had no intent of easing, even as a second wave of the coronavirus hit Beijing over the weekend.

While it’s commendable that the central bank wants to send its money to Main Street, is this sudden policy flip-flop a good idea? Why should anyone invest in a market where basic funding costs take a roller-coaster ride on a daily basis?

Ultimately, the problem is that China has too many interest rates. On the wholesale banking side, borrowing costs have come down, thanks to cuts in the MLF and reverse repo rate. But on the consumer banking side, the one-year benchmark deposit rate hasn’t changed since 2015, because much-hyped reform never happened. As a result, retail investors expect the yield on wealth management products to remain high. Hence, the levered-up carry trade.

But with all these rates, it’s hard to gauge the real stance of monetary policy. The PBOC now comes across as clueless, unaware that its shifting stance has serious knock-on effects. Even with the best of intentions, such an inconsistent framework derails China’s resolve to open its financial markets to foreigners. A market with too much interest rate volatility is a scary proposition.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.