The Bond Market Eats Its Own Cooking

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The biggest debate in the global financial markets these days is over exactly what signal the recent moves in U.S. Treasury securities are sending. As almost everyone knows by now, the most important part of the yield curve inverted late last week, with rates on 10-year notes falling below those on three-month bills. But it seems that for everyone who says this is an ominous signal portending a recession, someone else is saying the move is more technical in nature.

For one day, at least, those predicting doom and gloom look to be on the right side of the argument. That can be seen in the Treasury Department’s auction of $40 billion in two-year notes on Tuesday. Despite a big rally that has pushed yields on the notes down to 2.22 percent this week, the lowest since last March and down from 2.50 percent at last month’s auction, investors couldn’t get enough of them. They placed bids 2.60 times the amount offered, the highest bid-to-cover ratio since November, when yields were at 2.84 percent. Not only that, but the yield of 2.26 percent on the new notes came in just below the 2.27 percent level they were trading at in the so-called when-issued market, further evidence of strong demand. None of this would have happened if bond traders truly believed that the inverted yield curve was sending a false signal, that a recession wasn’t on the horizon and that the Federal Reserve wouldn’t be forced to cut interest rates by the end of the year. It didn’t hurt that just a few hours before the auction, the Conference Board came out with a weak consumer confidence report. The Present Conditions portion of the index fell in March by the most since 2008 as the outlook for jobs deteriorated. That suggested February’s poor employment report, which showed just 20,000 jobs were added, was no fluke.

Of course, it’s possible that the auction was juiced by the last remnants of traders who were short the bond market finally capitulating and using the sale to cover their positions. The answer to that question may be revealed in the remaining auctions this week. The Treasury will auction $18 billion of two-year floating-rate notes and $41 billion of five-year notes Wednesday and $32 billion of seven-year notes Thursday.

BUYBACKS UNDER ATTACK

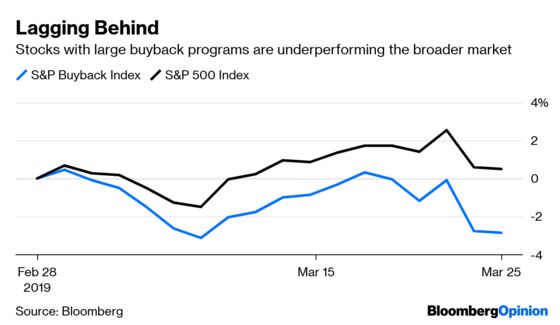

The U.S. stock market came out of the gates strong Tuesday, with the S&P 500 Index rising as much as 1.3 percent. Equities then spent much of the day giving back most of those gains to end up 0.72 percent. As is usual, it’s hard to pin the daily stock fluctuations on a single reason, but it would be hard to discount the increased scrutiny on stock buybacks by Congress. Lawmakers were scheduled to hold a hearing Tuesday on the matter titled: “Reward Work, Not Wealth: Creating Shared Prosperity in America by Reining in Corporate Stock Buybacks and Empowering Workers.” Most strategists agree that a surge in stock repurchases has helped underpin equities markets. JPMorgan Chase estimates that about two-thirds of the $430 billion repatriated from overseas last year by U.S. companies went toward buybacks. That’s not what the White House intended when it pushed through tax changes that made it less costly for U.S. companies to bring back cash from overseas. But the repatriation of overseas dollar is largely thought to be a temporary benefit, and companies have most likely brought back all the cash sitting outside the U.S. that they wanted to repatriate. Regardless, stocks with big buyback programs are lagging. The S&P 500 Buyback Index was down 2.83 percent this month through Monday, while the broader S&P 500 was up 0.50 percent. It’s been years since the buyback index undperformed by more in a month.

COMMODITIES KNOW NOTHING

Largely lost in the debate about whether the bond or stock market is sending the correct signal about the economic outlook (bonds are pessimistic; stocks are optimistic) is the signal being sent by the commodities market. The Bloomberg Commodity Index is up a respectable 6.87 percent this year but is still down 10.4 percent from last year’s high in May. Broad commodities indexes are heavily influenced by energy prices, specifically oil. West Texas Intermediate crude has soared 32 percent in 2019, but that increase is due largely to tighter supplies, not greater demand. Russia Energy Minister Alexander Novak told reporters in Moscow that the country, which is the world’s second-largest crude exporter, would most likely reach its pledged output cut of 228,000 barrels a day by the end of the month, according to Bloomberg News’s Ben Foldy. OPEC and its partners, led by Saudi Arabia, have been cutting supplies to counter a global supply glut and support prices. Then there’s copper, which has dropped to a one-month low, which “certainly appears to corroborate growing concerns for the global economy,” BNY Mellon strategist Neil Mellor wrote in a research note Tuesday. “Unfortunately, few other commodities allow for such a straightforward assessment: weakened platinum prices have to be seen in the context of the collapse in the diesel vehicle market, for example, whilst rising gold and silver prices may simply be a knee-jerk reaction to sliding bond yields. Iron ore and coal prices have been in the grip of Cyclone Veronica,” Mellor added. The debate continues.

THE EURO’S NOT DEAD YET

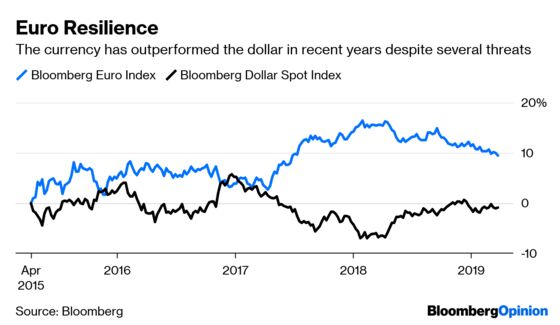

Since its introduction in 1999, the euro has had its share of existential crisis. There have been numerous times since the financial crisis alone when the shared currency was in jeopardy of breaking up. Lawmakers in Greece, Spain and Italy have all speculated whether their economies would benefit by going back to the drachma, peso and lira. As such, many feel there is a discount on euro zone financial assets reflecting the tenuous existence of the euro, despite what authorities say about its strength. They may be right. Former Swedish Prime Minister Goran Persson said joining the euro would protect the country against the volatility of the currency markets. Sweden, he added, only has itself to blame as businesses and investors seek cover from the worst slump in the Nordic country’s currency in a decade. “This is a good illustration of a vulnerability that’s completely self-inflicted when we decided to stay outside the euro,” Persson, who served as prime minister from 1996 to 2006, told Bloomberg News in an interview. Sweden’s long economic expansion is cooling, which is raising doubts that the central bank will be able to lift interest rates above zero, Bloomberg News reports. The slump is pressuring large parts of the economy, in particular those businesses that rely on imports. But for all of the euro’s perceived faults, it’s proved to be resilient. The Bloomberg Euro Index is up 9.95 percent from its lows in 2015, compared with a decline of 1.31 percent in the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index.

THE RACE IS ON

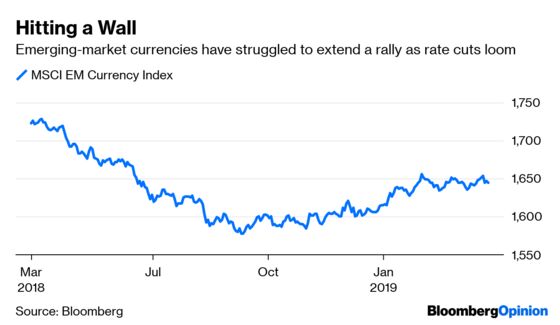

The thing about the globalization of the world economy in recent years is that it’s become difficult for any one country to buck the trend. Yes, the Fed has been able to tighten monetary policy in contrast with its major peers, but the massive size of America’s economy means it’s an exception. But now, global economic growth is decelerating to the point where even the U.S. has had to reverse course and put future interest-rate increases on hold. The focus now turns to emerging markets, and the question is no longer if any emerging markets will cut interest rates, but which one will be first, according to Bloomberg News’s Aline Oyamada and George Lei. Forward contracts and swap rates are showing wagers that central banks in Russia, the Philippines and Mexico will reduce borrowing costs this year, while markets such as South Africa and Brazil have erased bets on rate hikes. This may help explain the recent malaise in emerging-market currencies. After rallying 5 percent between early September and the end of January, the MSCI EM Currency Index has struggled, losing 0.68 percent while seeing a jump in volatility. A weaker currency can be a double-edged sword for many emerging-market currencies. While they may help make exports more competitive, they also have the potential to spark faster inflation as import and energy costs rise. And unlike in developed economies, the lack of inflation isn’t really the problem for many emerging markets; it’s that inflation is running a bit hot. Annual inflation in Russia quickened to 5.3 percent as of March 18, above the central bank’s 4 percent target. Brazil said Tuesday that its mid-March inflation accelerated the most since October on the back of a surge in food costs.

TEA LEAVES

The U.S. government on Wednesday will provide updated data on the current account. Although the data will be for the fourth quarter, it would be shortsighted to dismiss it as old — it is the broadest measure of trade because it includes investment. The median estimate of economists surveyed by Bloomberg is for the deficit in the current account to widen to $130 billion, which would be the biggest shortfall since 2008. A widening deficit is generally a net negative for a currency because it means that a country becomes increasingly reliant on foreign investment to the fund the shortfall. This could become a problem for the U.S. given that foreign-exchange reserve managers and central banks have generally avoided the dollar of late. The International Monetary Fund’s latest quarterly report on global foreign-exchange reserves released Dec. 31 showed that the dollar accounted for 61.9 percent of global reserves at the end of the third quarter, the lowest level since 2013. To be sure, the current-account deficit is a long way from the more than $200 billion it reached in 2006, a period in which the U.S. Dollar Index depreciated five out of six years. Nevertheless, it may be time to pay attention to the current account again.

DON’T MISS

The Fed Doesn’t Understand How Inflation Works: James Bianco

High Risk Is Not the Answer to Negative Yields: Brian Chappatta

Struggling to Reach 2 Percent Inflation? Try Three!: Daniel Moss

The Muscle That Backed China’s Stimulus Is Quaking: Shuli Ren

Turkey’s Problems Appear to Be Ring-Fenced: Marcus Ashworth

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.