The Amazing Admissions Advantages for Athletes at the Apex of Academia

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Ohio State University is famous as a sports powerhouse. The same can’t really be said of Amherst College, a small liberal arts school in Massachusetts known mainly for academics.

But Amherst prides itself on having “the oldest athletics program in the nation,” and it boasts 27 intercollegiate teams to Ohio State’s 37 or so (it depends on what and how you count). According to the U.S. Department of Education, there are 593 student-athletes at Amherst and 1,065 at Ohio State. Divide those numbers by the undergraduate student populations — 1,849 at Amherst and 46,820 at OSU’s main campus in Columbus — and it turns out that 32 percent of Amherst students are intercollegiate athletes, compared with just 2.3 percent at Ohio State. Amherst’s football team alone makes up 4.1 percent of the student body. Which one was the sports powerhouse again?

Obviously there are a bunch of other important ways in which Amherst’s approach to sports differs from Ohio State’s. It doesn’t have athletic scholarships, TV contracts, a gigantic football stadium or a football coach who makes $7.6 million a year. In fact, its entire athletics budget ($7.2 million, again according to the Department of Education) is less than that. It competes not in the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s Division I but in the much-lower-profile Division III.

But compete it does, with 11 national team championships in the past decade. In order to give those teams a better shot at winning, Amherst tips its admissions scale in a big way to favor athletes. According to a 2016 report on “The Place of Athletics at Amherst College,” there are 67 admissions slots reserved for “athletic factor athletes” who “are identified by coaches and endorsed by the Department of Athletics as prospective students who truly excel at their sports, and whose presence would have a significant impact on the success of their teams,” and another 60 to 90 for “coded” athletes with excellent or very good academic qualifications who are “admitted at a much higher rate than the general admission rate” for non-athletes with similar qualifications. At a college with 471 students in its freshman class, that’s a lot (anywhere from 27 percent to 33 percent of the total).

Amherst’s athletic efforts are pretty ambitious for a liberal arts college, but not unique — three of its rivals in the New England Small College Athletic Conference have student bodies that are 36 percent athlete. At the larger Ivy League universities, the figure is usually a little under 20 percent, but since in sports other than football the Ivy League teams are competing at the very highest collegiate level, the competitive pressures weighing on recruiting and admissions are presumably greater there. Because the Division III and Ivy League schools don’t award athletic scholarships, they also have to over-recruit in a way that the Ohio States of the world don’t: Once admitted, athletes don’t risk losing financial aid if they quit the team or never even show up for the first practice. Big-time, big-money college sports as practiced at places like Ohio State raises all kinds of important and difficult questions about its potential corrupting influence and its unfairness to the unpaid athletes, but it has a minimal impact on the makeup of the student body. At Amherst and its peers, that impact is huge.

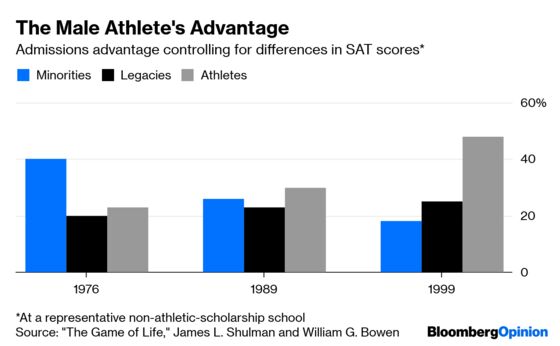

If you were wondering why so many of the students caught up in the Varsity Blues college admissions scandal’s faked sports credentials, this is a key reason. Getting recruited as an athlete is perhaps the single biggest leg up one can get in the elite-college admissions game in the U.S., far bigger than being a member of a minority group or an alumni child. I add the “perhaps” because I would guess that children of alumni and others who are able and willing to donate millions of dollars get an even bigger advantage, but it’s tough to find statistics on that. There are, however, numbers available on the admissions advantages of minorities, legacies and athletes at one unnamed non-athletic-scholarship-granting institution (that is, an Ivy League or Division III school) from the 1970s through the late 1990s. Here are the statistics for male applicants:

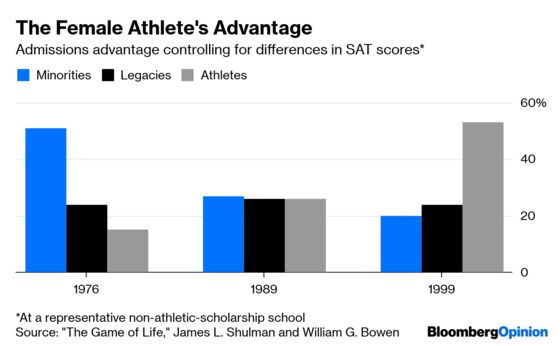

And here they are for female applicants:

These statistics are from “The Game of Life: College Sports and Educational Values,” an eye-opening and important 2001 book that I finally got around to reading last weekend. The numbers are obviously a bit old, but co-author James L. Shulman told me he figures the trends apparent in the above charts have continued. It’s not that the athletes are getting dumber, just that the overall competition to get into top schools has gotten so much more intense that the admissions advantage conferred by athletic skill keeps growing.

Why do colleges and universities with great academic reputations go to such lengths to fill their sports teams with ringers? Partly because athletics has been central to student life at these schools for more than a century, write Shulman, now the vice president and chief operating officer of the American Council of Learned Societies, and his co-author, William G. Bowen, a former president of Princeton University and of the Mellon Foundation who died in 2016. “The battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton,” the Duke of Wellington is (probably incorrectly) reputed to have said at some point after that 1815 triumph, and in the late 1800s the leaders of America’s colleges and universities also began to see competitive sports as a way to teach skills and instill values. For student-athletes who predated the era of widespread recruiting — men who attended college in the 1950s, and women who went in the 1970s — Shulman and Bowen found much support in the data for the argument that sports experiences fostered leadership, success and loyalty to the alma mater.

After that, though, the picture muddies. By the late 1980s, athletes had become marked academic underperformers at the schools Shulman and Bowen studied, not just in absolute terms but relative to their expected performance as predicted by standardized test scores. Shulman and Bowen also found declining athlete involvement in student life outside of sports, and declining rates of alumni giving, especially among athletes in the high-profile sports of basketball, football and ice hockey. Male athletes remained more successful financially than other students after college, but this could be explained mostly by (1) a higher percentage of them going into business rather than nonprofit pursuits and (2) a higher percentage of those in business going into finance.

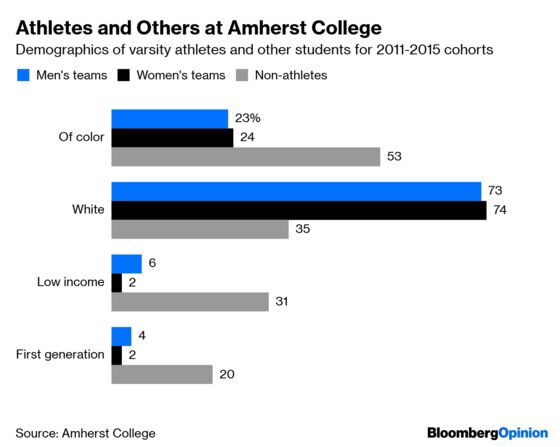

This is diversity of a sort. College athletes have more conservative political views than other students, and they choose different career paths. But in making room for so many athletes, small colleges such as Amherst make it much harder to obtain other kinds of diversity. Here, for example, are some rather stunning statistics from that 2016 report on the place of athletics at Amherst:

At places like Ohio State, athletes — at least in football and basketball — add racial and economic diversity. At Amherst and many schools like it, the athletes are mostly white and usually from families that can bear (and understand the potential payoff from) the many demands of travel hockey or travel soccer, or the cost of prep schools with great lacrosse or field hockey programs. In conjunction with the entirely admirable efforts in recent years to increase socioeconomic diversity on campus, this helps explain why the college admission competition has gotten so much more intense for upper-middle-class kids who aren’t star athletes. It also helps explain why my high school in suburban California, where the sport was previously unknown, now has a lacrosse team. I had thought this was pure affectation, but I guess it’s mostly just a rational response to how college admissions work. So is the recent growth in high school and youth crew programs. “Crew is the last amateur sport,” says a college dean in Shulman and Bowen’s book, because teams were composed mostly of walk-ons who had never rowed before. Even that now seems to be changing.

It’s changing because college coaches and athletics directors feel pressured by the forces of competition to keep intensifying their recruiting efforts. “It is almost impossible to have an extended conversation with an athletics director of a program operating at any level of play,” Shulman and Bowen write, “without hearing the metaphor of an arms race invoked.” What’s odd about the Ivy League schools and liberal arts colleges, though, is that the rewards to victory in the sports arms race are so unclear for them. Their athletic programs generate almost no revenue, and they don’t play a notable role (unlike, say, football at the University of Alabama) in enhancing the schools’ visibility or prestige. As for the much-rumored connection between sports success and alumni giving, Shulman and Bowen found no statistical link between winning football records and giving at large universities or Ivy League schools, and just a modest positive relationship at liberal arts colleges such as Amherst — where, remember, about a third of the alumni are former intercollegiate athletes. Alumni of losing teams actually gave more money than those who had played for winners.

What every college president knows, though, is that poorly performing basketball and football teams generate cranky comments at alumni gatherings, and that an attempt to shut down or downgrade even a sports team with no fan following will meet with intense opposition from alumni of that particular team. Shulman and Bowen tell the story of one such attempt in their book — Princeton’s subsequently revoked 1993 decision to get rid of wrestling, which is a particular bane of admissions officers because teams need not only good wrestlers but good wrestlers of specific weight classes. I have a suspicion that the entire edifice of intercollegiate athletics at elite colleges and universities continues to exist in its present form not so much because college presidents think it’s good as that they see attempting to change it as just too much hassle.

Still, there is one big hassle they probably won’t be able to avoid: deciding the fate of football, which because of player-health concerns is in decline as a high school sport in most of the country. It’s a little hard to see how institutions dedicated to intellectual excellence can continue to sponsor a sport that so reliably causes brain damage. Given that football requires much larger teams than any other sport, shutting it down would mean a marked reduction of the intercollegiate athletic footprint at places like Amherst. I’m a Princeton alumnus who attended every single home football game during my years there, so this prospect doesn’t exactly fill me with joy. But it would be an opportunity to shift a trajectory that really does seem unsustainable.

Ohio State has several small teams of men and women bearing weapons (fencing, rifle, pistol) that are counted as two teams each to get to the 37 total, as is the spirit squad. Amherst, meanwhile, counts indoor and outdoor track and field as separate teams but doesn't seem to have any cheerleaders.

Bates, Bowdoin and Williams.

Just to get all the disclosures in one place: My father and grandfather went to Princeton, so I was one of those legacy admittees. I was a (bad) high school athlete, and stuck to intramurals at Princeton. My son is a student at Williams College, Amherst's archrival, where he is neither a legacy nor an intercollegiate athlete. Bowen's last four years as Princeton president coincided with my time there, and we met for diner breakfasts a few times after that when he was at the Mellon Foundation. He may have paid once or twice.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.