(Bloomberg Opinion) -- President Trump’s assorted statements on asylum seekers often range from unhelpful to disgraceful — migrant caravans are attempting “an invasion,” or “This has nothing to do with asylum; this has to do with getting into our country illegally,” and so forth. But he’s actually right about one thing. The U.S. asylum system is near the point of collapse.

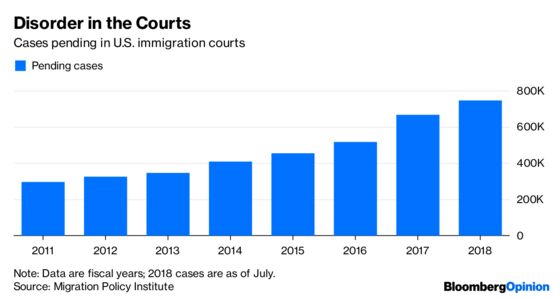

The number of asylum cases has more than quadrupled since 2010, feeding a backlog of hundreds of thousands. As a result, legitimate asylum cases languish, even as fraud and abuse of the system rise. The bigger the backlog in the asylum queue and the immigration courts, the greater the incentive for more would-be migrants to file asylum claims that allow them to enter and remain in the U.S.

To wit: Thanks to a combination of the backlog and U.S. laws and rules governing the detention of families and minors, a staggering 99 percent of the 94,285 Central Americans who were apprehended in 2017 entering the U.S. illegally as a family unit are still here. Of those from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras who seek asylum, only a relatively small proportion — in some cases, 15 percent or less — may ultimately qualify, often after waiting years for a hearing. Yet the U.S. has an obligation to judge all their claims that is not just codified in domestic and international law, but also consistent with its humanitarian values and tradition.

Unfortunately, this crush of asylum seekers overwhelming the system has turned potentially life-or-death decisions into a legal and administrative crapshoot. Worse yet, the Trump administration’s efforts to curtail access to asylum at the Southwest border through “metering” punish the good as well as the bad, creating a needless humanitarian emergency and potentially disrupting the billion dollars a day in legitimate commerce that flows across the border.

The problem is soluble — and it doesn’t require the U.S. to send more troops or shut down “the whole border,” as Trump seems to prefer. There’s no need, either, to clamp down on grants of asylum. In 2017, the U.S. gave asylum to 26,568 applicants — just over 1 percent of the growth in last year’s total U.S. population. The solution, instead, is simply to make the asylum system work more efficiently.

Under U.S. law, any alien who is present or who arrives in the U.S. — “whether or not at a designated port of arrival” and regardless of their legal status — may apply for asylum. (Note that applications for refugee status are different. These have accounted since 1980 for more than four times as many admissions as asylum seekers — but would-be refugees make their case from outside the U.S.) The main question is, how should these applications for asylum be handled?

A well-functioning asylum system would conform to U.S. law and uphold the international conventions to which the U.S. is a party. Its outcomes would be consistent, predictable and transparent. Its processes would be efficient, cost-effective and humane. And it would be seen as just and competent by the citizens whose interests it should strive to defend. In all these areas, the U.S. has much work to do.

The requirements of the law aren’t always clear-cut. In some areas, international and U.S. law create obligations that are incontestable, but in others they invite constant struggle. In recent years, the stakes in this struggle have grown, because record numbers of people have sought refuge from conflict, misery and persecution around the globe.

The right to seek asylum set out in the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees is one of the most widely recognized principles of international law. It requires states to give refugee/asylee status to any person seeking protection “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” A 1967 protocol expanded the convention’s remit beyond those displaced by the Second World War in Europe.

Surprisingly for a country whose early European settlers famously fled religious persecution, and whose ranks were subsequently filled by those seeking other forms of refuge, the U.S.’s first refugee legislation was the 1948 Displaced Persons Act. This brought in 400,000 postwar European refugees. During the Cold War, the U.S. saw refugee and asylum policy as a weapon against communism. Even after the U.S. ratified the protocol to the convention in 1968, observed legal scholar Deborah Anker, “persons fleeing governments friendly to the U.S. had a nearly impossible time getting asylum.” Only with the 1980 Refugee Act did the U.S. adopt the UN’s more expansive and nondiscriminatory vision of refugees and asylum seekers.

The UN convention enshrined the right to seek asylum — but not the right to asylum in any particular country. States had latitude in judging “well-founded fear of persecution.” States were forbidden to send asylees to countries where they might be persecuted — the principle of non-refoulement. And they couldn’t penalize asylum seekers or refugees for illegal entry “from a territory where their life or freedom was threatened.”

States are allowed to send asylum seekers back to countries they have traveled through, or even to refugee camps administered in third countries, so long as these are deemed safe. Members of the European Union have exercised these options. And the Trump administration’s efforts to conclude a safe third-country agreement with Mexico — like the one it has with Canada — is consistent with U.S. obligations under the convention. The U.S. doesn’t necessarily have to resettle qualified asylum seekers within its borders.

A larger unresolved question is who deserves asylum in the first place. Four grounds for protection — persecution because of race, religion, nationality or political opinion — are relatively straightforward. The fifth ground — “membership of a particular social group” — could mean almost anything.

This has opened up a legal free-for-all across the European Union, North America and most states that receive asylum claims. Boyce Robert Owens, a sociologist of law, looked at records in the U.S. courts of appeals and found 33 distinct disputes over the meaning of “particular social group.” Candidates have included “ethnic Sinhalese,” “landowning cattle ranchers targeted by Maoist groups,” “Albanian women forced into prostitution,” and “schizophrenic and bipolar individuals in Tanzania who exhibit outwardly erratic behavior.”

Many of those from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras arriving at the U.S. border invoke gang and domestic violence as the basis for their claims. Even within the U.S., the law on this is far from settled, fueling an enormous variation in asylum outcomes. In Los Angeles, judges over the past five years have granted asylum at rates ranging from 3 percent of applications to 71 percent; in San Francisco, from 3 percent to 91 percent. Asylum officers know that claims based on gang and domestic violence are a judicial lottery, so they often simply pass cases along to the courts — allowing applicants to remain in the country and make their case before a judge. No sane person would call this process consistent, predictable and transparent.

Last June, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions ruled that claims based on domestic or gang violence generally won’t qualify for asylum. Many thought this harsh — and it certainly cuts against some U.S. case law. But his position is not obviously out of line with that taken by some other governments. Sessions had a point in arguing that “We are really returning to the classical understanding of what asylum is.”

However, the classical understanding no longer fits. In 1951, the world looked very different to the convention’s 19 mostly European signatories. Indeed, the UN’s 60 members weren’t much concerned with non-state actors, transnational gangs and failed states. Today, its 193 members — 148 of whom ascribe to the convention or protocol — are very much concerned. But it’s one thing to ask states to provide refuge to victims of a predatory, malevolent government, and quite another to ask them to throw their doors open ever wider to those fleeing failed or failing states. (The Fragile States Index puts more than 30 in its red “alert” category.) If that’s to be demanded of nations, the edict perhaps ought to come from an updated convention — not from a welter of contradictory rulings from national courts and guidelines drawn up by UN bureaucrats.

Be that as it may, the past decade’s surge in applications from Central Americans belonging to “particular social groups” and seeking protection from non-state actors accounts for much of the gridlock in the U.S. asylum system.

Complications over what the law means or ought to mean are certainly part of the problem. But they are vastly compounded by the procedural complexities of the U.S. system — and by the lack of adequate resources to manage the consequences. Prepare to enter a maze from which some never emerge.

A migrant already in the U.S. can apply “affirmatively” for asylum before an officer of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Someone seeking a reversal of an adverse affirmative case ruling or otherwise facing deportation can apply “defensively” before a judge in an immigration court overseen by the Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review. Those who cross the border without proper documentation are subject to expedited removal without the benefit of a hearing before an immigration judge. But if they express a fear of returning to their home country, they get a “credible fear” review with an asylum officer that seeks to establish if they have a “significant possibility” of gaining asylum. And if applicants pass their credible-fear reviews, they then make their case before an immigration judge.

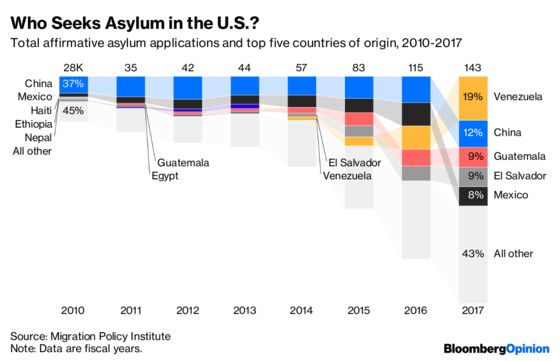

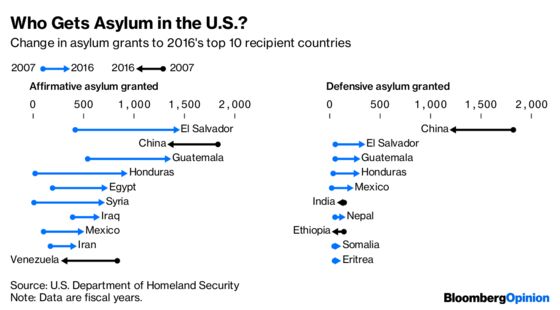

Suffice it to say, this is not a system well-suited to cope with a surge in applications. In the last two years, for instance, Venezuelans who fear returning to their imploding autocracy have been the leading affirmative applicants for asylum in the U.S. But especially since 2014, applicants from the countries of the Northern Triangle (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras) have been key drivers in affirmative filings (which rose from about 57,000 to about 143,000 in 2017), defensive claims (from 33,000 in 2010 to 120,000 in 2017), and credible-fear screenings (from about 9,000 in 2010 to nearly 100,000 in 2018).

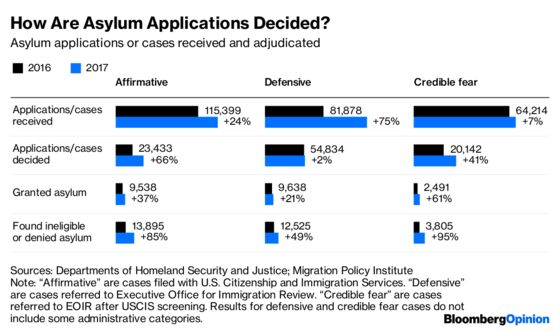

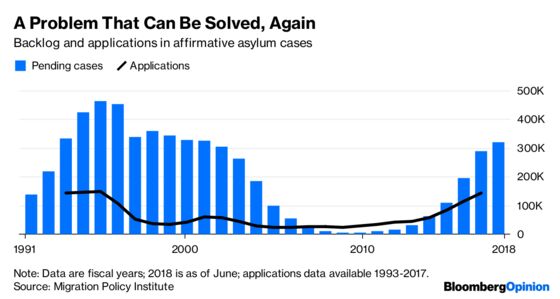

The spike in each type of case has cascaded through the system. Asylum cases now account for as much as 30 percent of the immigration courts’ total backlog — which stood at nearly 750,000 cases in July this year. According to the Migration Policy Institute, last year 40 percent of USCIS’s asylum officers were occupied with credible-fear reviews — making it harder to reduce the backlog of 320,000 affirmative cases.

It would be one thing if the credible-fear track were mostly dealing with legitimate claims, but this is not so. Only about half of those who pass a first credible-fear screening end up submitting the required written application. Many, it seems, melt into the background and stay in the U.S. illegally; and many of those who do complete the paperwork are rejected. All told, in 2017, judges granted asylum to just over one in 10 of those adults who passed their credible-fear screening.

The backlog across the system as a whole creates a gaping loophole. It can take up to five years for an asylum case to be heard and resolved — but U.S. law enables applicants whose cases have not been processed in six months to receive work authorization. Such approvals jumped from 55,000 in 2012 to 278,000 in just the first half of 2017. And keep in mind that although refugees are rigorously vetted overseas before entering the U.S., asylum applicants who are released to await their court dates don’t receive an equally serious screening.

The affirmative-claim track has more formal safeguards than credible fear claimants and doesn’t clog the courts as badly — but it has problems of its own. Andrew Arthur, a former immigration judge now at the Center for Immigration Studies, said in an interview that “fraud in the process is still widespread and hard to catch.” One celebrated case: In 2012, New York City attorneys and preparers who had filed thousands of affirmative asylum applications were charged in Operation Fiction Writer with helping to concoct fake stories of persecution. The U.S. is seeking to deport 13,500 beneficiaries of the scheme.

The Trump administration has tried to limit access to the system and deter applicants through punitive measures. This hasn’t deterred the caravans, but it has run afoul of law and public opinion. On Nov. 19, a federal judge ruled that Trump’s executive order narrowing access to those who present themselves at ports of entry was unlawful. Trump’s earlier decision to detain asylum-seeking families while separating children from their parents triggered public outrage as well as court challenges. Confirming the pattern, the idea backfired: The controversy, and the inevitable reversal, reinforced that heading to the border with children in tow was a good bet.

Trump’s latest gambit is to strike a deal with Mexico to allow the U.S. to keep asylum applicants south of the border until their cases can be heard. Its prospects are unclear.

Experience shows that the most effective approach to the issue is simpler than you might think: Process cases faster. This would not only deliver legitimate asylum applicants from limbo more promptly, it would also cut the backlog, and hence the incentive to enter the country illegally.

As the Migration Policy Institute notes, during the mid-1990s, the U.S. faced an influx of asylum seekers (including many from Central America) that led to record numbers of claims (150,000 in 1995) and a backlog of nearly 500,000 affirmative asylum cases. Over three years, from 2003 to 2006, reforms and more resources reduced that from 464,000 to 55,000, and then to 6,000 by 2010. Instead of restricting access through legally dubious executive orders, the U.S. should be devoting more resources to processing cases, and do so more efficiently — for instance, by keeping the cases of those who pass their initial “credible fear” screenings with Citizenship and Immigration Services to adjudicate, rather than kicking them over to the courts for adjudication years later. That kind of solution affirms U.S. values, and promises far better results than a costly military deployment. The southwest border doesn’t need soldiers; it needs more asylum officers and judges.

Comprehensive immigration reform is needed as well. For one thing, the flood of applicants reflects the pull factor of Central Americans already in the U.S., many of them illegally. More than three-quarters of the unaccompanied minors arriving from the region in 2014, for example, had family members already in the U.S. Some 50,000 cases in the affirmative-asylum backlog were filed by undocumented residents who have been in the U.S. for a decade. (Many of these will be denied — but applicants will then get a shot at the already crowded immigration courts for what’s known as “cancellation of removal,” because of the hardship their deportation could impose on relatives who are citizens or green-card holders.) Trump’s plan to deport nearly 350,000 Central Americans in the U.S. under temporary protected status would launch a new raft of asylum claims.

The best way to keep the Northern Triangle’s desperate citizens from heading north is to help them become less desperate. The U.S. has a strong interest in continuing its foreign aid to improve governance and security, and spur development. In 2017, the U.S. provided $420 million to El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras — about 2 percent of the $18 billion that Trump has requested for his wall. Better to strengthen weak states than stretch asylum law to encompass “particular social groups” that are impossible to define, much less verify.

Trump has repeatedly threatened to halt aid to the Northern Triangle. Earlier this summer, he tweeted, “We cannot allow all of these people to invade our Country. When somebody comes in, we must immediately, with no Judges or Court Cases, bring them back from where they came.” This repudiation of U.S. law and international obligations is of a piece with his attempted travel bans and cuts in refugee admissions. The U.S. asylum system is failing — but the main obstacle to fixing it is the man in charge.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Clive Crook at ccrook5@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

James Gibney writes editorials on international affairs for Bloomberg Opinion. Previously an editor at the Atlantic, the New York Times, Smithsonian, Foreign Policy and the New Republic, he was also in the U.S. Foreign Service from 1989 to 1997 in India, Japan and Washington.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.